Can Sanctions be “Smart”? Lessons from Iraq

Published on

Since May 2002 targeted, or “smart”, sanctions have been put forward as the new solution to the world’s problems. But do sanctions really work? Iraq’s experience would suggest not

On August 6th 1990, in response to the invasion of Kuwait four days earlier, the UN Security Council imposed economic sanctions on Iraq that barred all imports (except medical supplies) into and exports out of the country. After the withdrawal of Iraqi troops from Kuwait following the US-led invasion of the country in 1991, the Council maintained the sanctions in order to press for Saddam Hussein’s further disarmament and attain an eventual regime change. But they didn’t work: after more than 12 years of sanctions (only partially relieved by the UN Oil-for-Food Programme started in 1997), they were only removed after the March 2003 military intervention, once again led by the US government.

On August 6th 1990, in response to the invasion of Kuwait four days earlier, the UN Security Council imposed economic sanctions on Iraq that barred all imports (except medical supplies) into and exports out of the country. After the withdrawal of Iraqi troops from Kuwait following the US-led invasion of the country in 1991, the Council maintained the sanctions in order to press for Saddam Hussein’s further disarmament and attain an eventual regime change. But they didn’t work: after more than 12 years of sanctions (only partially relieved by the UN Oil-for-Food Programme started in 1997), they were only removed after the March 2003 military intervention, once again led by the US government.

Sanctions can be defined as both the most coercive of the many negotiating instruments and the least violent of all belligerent techniques. Undoubtedly, sanctions’ effectiveness is ambiguous. Those imposed on Iraq, which were described by a spokesman from the US State Department as “the toughest, most comprehensive sanctions in history”, isolated Saddam Hussein’s regime and temporarily prevented the outbreak of hostilities. However, it was the Iraqi population which bore the brunt of the hardship caused by the country’s ostracism. Moreover, the carefully crafted Oil-for-Food Programme, aimed at alleviating the suffering of the Iraqi people in the face of the sanctions, proved disastrous.

Does the Iraqi case testify to the ineffectiveness of sanctions? That is, did sanctions fail because of inadequate management and Washington’s resolute determination to invade Iraq or, alternatively, would sanctions have eventually acted as a catalyst in the overthrow of the Hussein regime had they been more strictly enforced and given more time to work?

The Ongoing Debate

Many proponents of sanctions argue that they can be effective if they are adequately complemented with incentives. This explains why, despite their coercive nature, sanctions are preferred over other foreign policy strategies such as deterrence and forced compliance.

Authors like David Baldwin stress the potential benefits derived from sanctions by emphasizing how positive coercion can prevent conflict. According to Baldwin, when dialogue fails, an appropriate combination of carrots and sticks can help achieve desired goals without resorting to the use of force. Others like Richard Haas and Meghan O’Sullivan, the authors of the widely acclaimed book Honey and Vinegar, underscore the secondary consequences of sanctions (which often don’t affect the initially intended targets): potentially disastrous humanitarian consequences for the poorest segments of the population; damaging side-effects for world trade and third parties; the contrary result of strengthening the domestic popularity of the regimes they aim to weaken; and the challenge posed to their effectiveness by circumventing states.

Sanctions on Iraq

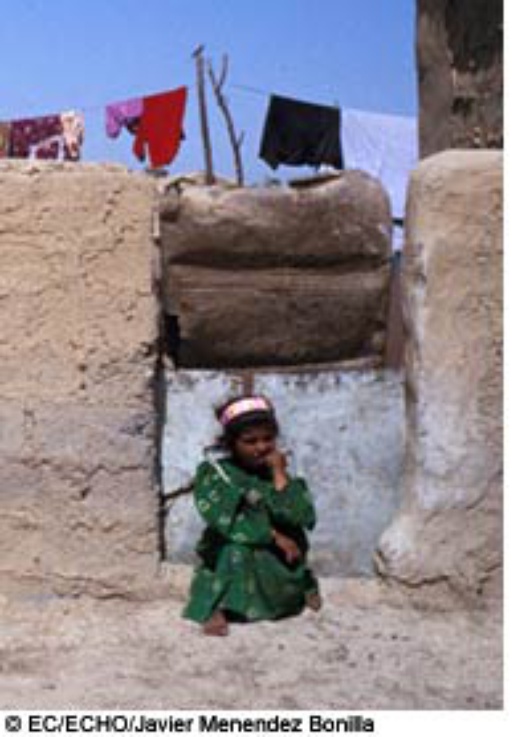

Since 1990, Iraq has experienced a severe deterioration in living standards as a result of UN imposed sanctions. In 1997, for example, the UN Human Rights Committee noted that, “The effect of sanctions and blockades has been to cause suffering and death in Iraq, especially to children.” Echoing that sentiment, a humanitarian panel created by the Security Council in 1999 concluded that, “Even if not all suffering in Iraq can be imputed to external factors, especially sanctions, the Iraqi people would not be undergoing such deprivations in the absence of prolonged measures imposed by the Security Council and the effects of the war.” Even the Security Council’s Resolution of that year indirectly admitted this negative effect by saying that the fundamental objective of the possible suspension of sanctions was “improving the humanitarian situation in Iraq”.

Although the Iraqi government undermined the Oil-for-Food Program (by illegally skimming revenue, smuggling oil, and occasionally ceasing shipments of petroleum for political reasons), even without such subversion Iraq would have faced a humanitarian crisis since the programme was not envisioned as a full substitute for normal economic activity. Indeed, during its six years of implementation, the Oil-for-Food Programme generated only as much oil revenue ($63 billion) as Iraq earned from oil sales in 1980 alone ($59 billion).

By focusing on the effects of sanctions on the Iraqi government, the Security Council (led by the US and British governments) overlooked the root causes of the problems in Iraq and the effect such policies had on the population. Sanctions are, after all, instruments of coercion that achieve their ends by causing hardship. An honest assessment of the sanctions on Iraq must acknowledge that they were imposed because it was believed that the suffering they would cause was a price worth paying for the policy objectives being sought. As then US Ambassador to the UN, Madeleine Albright, said in 1996 in reference to the humanitarian costs of the sanctions on Iraq, “I think this is a very hard choice, but the price - we think the price is worth it.”

Are Sanctions still on the UN Agenda?

Despite the failures of the sanctions on Iraq, the UN will probably continue to act in a similar manner in the coming years in their attempts to ostracise regimes. The exponential increase in the use of sanctions is evident: while during the Cold War the UN imposed sanctions just twice (on Rhodesia in 1966 and South Africa in 1977), it used them sixteen times during the 1990s. Indeed, the recent report by the High-Level Panel on UN Reform, presented by Secretary General Kofi Annan last December, devotes an entire chapter to the role of sanctions. The report underscores the importance of sanctions as a vital, if imperfect, tool which act as “A necessary middle ground between war and words”.

Let us hope that the Security Council takes into account the 1999 Panel’s recommendations for future sanctions by: “improving their implementation, enforcement and monitoring mechanisms; using more selective measures tied to the specific cases; imposing secondary sanctions against sanctions-busters and violators; and mitigating their humanitarian consequences.”