Buying Red: Challenging capitalism from within

Published on

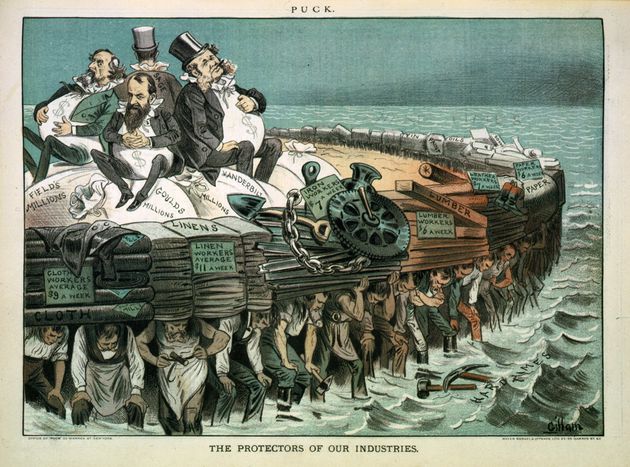

Our sense of identity is partly formed by the environment in which we buy goods and services. The skyline of capitalism is dominated by the pyramids of private profit-making corporations, with those at the bottom producing profit for those at the top. If we wish to rebuild this landscape democracitcally, then buying from cooperatives gives consumers a radical, red, alternative.

Alienation at work

Our working environments appear rigid; workers sit at the bottom, subservient, while the managers enforce order on behalf of owners of capital, resting at the peak of the pyramid.

This environment fosters alienation among workers who feel a lack of meaning and power in their jobs. In the UK 37% of workers believe their jobs are meaningless; in the US, 7 in 10 workers are disengaged. Elsewhere, just 6% of workers surveyed in China said they were engaged at work; 9% of workers in India; 5% in Tunisia; 16% in Argentina. A sense of workplace alienation is a worldwide phenomenon.

There are no ballot boxes in the office; no decisions are reached collectively by all workers. Capitalism contradicts economic democracy. However, cooperatives offer an alternative model where economics is guided by democracy. In his book Democracy at Work, the American economist Richard D. Wolff describes how workers collectively shape the direction of their workplace, which is controlled democratically, giving workers both a voice and a vote.

Buying red

Karl Marx wrote that that cooperative labour represents “within the old form the first sprouts of the new, although they naturally reproduce… all the shortcomings of the prevailing system.” Under cooperatives the contradiction between those who control capital and those who labour begin to evaporate, but still, cooperatives operate in a predominantly capitalist environment, in which they must compete. Workers may still be forced to lower their own wages, or cuts additional costs to stay competitive with capitalist companies.

This is recognised by the workers cooperative SUMA, who distributes among other things, vegetarian, organic and fair trade goods. “Suma discusses these ethical issues on a case by case basis,” said Jenny Carlyle, a warehouse worker and part of the Suma HR team, “and will make a decision that tries to balance ethical issues, the business issues and also customer needs.” Yet the key point here is that issues are confronted and resolved collectively by the workers, rather than by middle-aged executives concerned exclusively with profit. Hence, as Jenny suggests, “a cooperative is usually a fairer and more ethical way of operating a capitalist business.”

Even though cooperatives operate in a capitalist environment, they are structured in a way in which the key decisions of a company are open to debate, and where solutions are arrived at through a consensus by the workers, i.e. cooperatives operate through democracy at the workplace. This is a clear example of what Marx saw as “how a new mode of production naturally grows out of an old one.”

Workers gain agency, and that cloud of alienation and meaninglessness hanging over the workplace evaporates, given that “the people are central to the business and are all motivated for that business to succeed,” said Jenny.

A vote for democracy

Away from work, in our role as consumers we have the collective power to affect the economic system, no matter how small these shifts may be. Directing our money towards cooperatives acts as a vote to support economic democracy. SUMA, for example, has it written into their constitution that they give preference to products that are from other cooperatives, and also invest in and share knowledge with other cooperatives. By feeding one cooperative, you energise a chain of cooperatives.

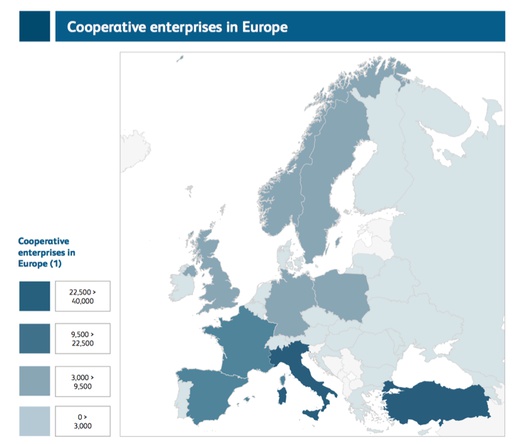

Fortunately, there are many cooperatives in Europe to choose from. Within the EU economy there are 250,000 cooperatives that are owned by 163 million citizens (one third of the EU population) which stretches across the economy from banking to agriculture and retail.

Citizens can shop for clothes in John Lewis stores in Britain; get groceries from Leclerc supermarkets in France, or REWE stores in Germany. There are coop stores in practically every EU nation. Cooperative Europe lists the largest profit-making cooperatives on the continent in their 2015 report.

Citizens can shop for clothes in John Lewis stores in Britain; get groceries from Leclerc supermarkets in France, or REWE stores in Germany. There are coop stores in practically every EU nation. Cooperative Europe lists the largest profit-making cooperatives on the continent in their 2015 report.

One local store in my area sells snacks, such as Bombay mix and dried banana slices, that are made by a cooperative. I first realised this after the packet was empty and decided to flip it over to check the ingredients. The next time I went in I decided to look for other coop products and, as a mild sugar addict, was delighted to discover the chocolate bars were made by Divine, a company that is 44% owned by a Ghanaian cocoa farmer cooperative.

Like all economic structures, criticisms are thrown at cooperatives: how can all workers make good management decisions? And where does the innovation come from if everyone has an equal voice? They are fair points. After all, every economic system has faults and must make compromises: in capitalistic enterprises, profits are prized over wages –when profits are dented by an economic crisis, workers are in the firing line. In cooperatives, the balance shifts towards the workers, and away from high profit-seeking. This tends to make these enterprises more conservative when it comes to innovation, as sustainability triumphs over high returns. “It is much more difficult to get 165 people to agree to an idea than it is for one,” says Jenny. This slower, consensus-based approach to innovation is attached to how some cooperatives view themselves, as Jenny adds: “High rewards come with high risks, and our experience is that our coop is risk averse, but this is linked to our key business driver of having a sustainable long-term business that looks after its workers.”

The media may be prone to placing lone entrepreneurs, like Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos, on pedestals, creating cult-like personalities in a culture that celebrates individualism. Yet cooperatives collect a whole range of experience and ideas from a team motivated to succeed. “If people work together then multiple levels of knowledge and experience can be drawn upon,” said Jenny. “As members are also central to the cooperative, investment in training is often easier to obtain in a coop than in a standard business, especially if there is an obvious skills gap within the coop.”

The elementary steps towards buying red may place us deep within the woods with no paths to follow; we’re in unchartered territory. Fortunately, with the simplest of searches, the internet has many potential paths and motivational material to guide us in how to bring ethics central to our consumer lives. And if you can’t find coop products in the shops, you’re bound to be found on online markets such as eBay and Amazon.

Buying red is not revolutionary, but it can be radical. In our role as democratic citizens, we vote in regular elections for politicians who supposed to represent us; in our role as consumers, we vote with our money, an active expression of individual and collective power.