Bulgarian anti-immigrant fence

Published on

A year after Greece completed its border fence with Turkey, Bulgarian authorities announced their own 30 kilometer fence. It is an effort to combat a spike in illegal migration following bloody fighting in Syria. This heavy handed approach will only lead to thousands more deaths and human suffering on the periphery of Europe. For many, the promised land becomes a kind of hell on earth

Like certain well-known maritime routes across the Mediterranean, the short land border between the EU and Turkey is a hotbed of illegal migration. The fences are just one piece of the EU's expensive attemps to police the border, which are widely criticised as inefficient and conducive to human rights abuses. Over the past years, Europe’s border with Turkey has become one of the most important points of entry for migrants from Asia, the Middle East and Africa. A decade ago, Spanish and Italian borders bore the full brunt of migrants fleeing war and destitution to come to Europe. As maritime border controls were beefed up and repatriation expedited – both Spain and Italy signed repatriation agreements with North African governments. Traffickers evolved accordingly.

Like certain well-known maritime routes across the Mediterranean, the short land border between the EU and Turkey is a hotbed of illegal migration. The fences are just one piece of the EU's expensive attemps to police the border, which are widely criticised as inefficient and conducive to human rights abuses. Over the past years, Europe’s border with Turkey has become one of the most important points of entry for migrants from Asia, the Middle East and Africa. A decade ago, Spanish and Italian borders bore the full brunt of migrants fleeing war and destitution to come to Europe. As maritime border controls were beefed up and repatriation expedited – both Spain and Italy signed repatriation agreements with North African governments. Traffickers evolved accordingly.

The hundreds of thousands of migrants that cross Europe’s borders every year from as far away as Afghanistan can pay up to $10, 000 to traffickers for the journey, making it a multi-million dollar industry authorities reckon. With so much money at stake, traffickers can adapt much faster than European border authorities can address the changing landscape of illegal migration.

100, 000 illegal immigrants a year

In 2011 alone, around 100, 000 illegal migrants were arrested trying to enter the EU through Greece, up from just 36, 000 in 2010. As immigrant flows intensified in south east Europe, Greek authorities felt as if they had been hit by a bus. 'We just can’t handle it,' said Greece’s secretary of citizen protection, Christos Papoutsis, in 2011. With cash-strapped authorities unable to bear the burden, asylum applications backed up and migrants found themselves packed into overpopulated facilities, suffering inhumane conditions for months.

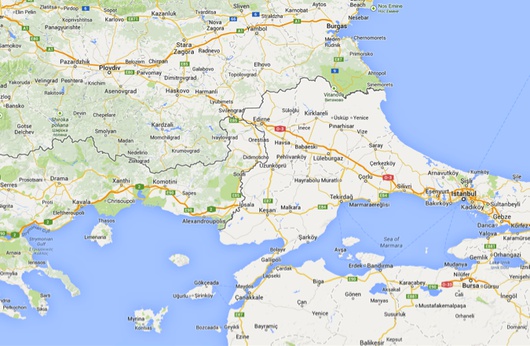

Greece completed its €3 million fence in December of 2009. The four meter tall barbed wire fence spans 10.5 kilometers, protecting a short stretch of dry land along the 125 mile border with Greece, most of which runs along the Evros River. Authorities say the fence has been effective, but it seems to have done little but force migrants to attempt riskier maritime or river crossings.

Greek border guards told local newspaper Kathimerini that the project had a huge impact on the flows of illegal immigrants across the land border. They claimed that illegal arrivals were down by 95%, however, there has also been a sharp spike in maritime crossings of the Aegean Sea. In the first semester of 2012, police and coast guard officers in the region detained 102 undocumented migrants, while 1, 536 were intercepted in the three months following the completion of the fence.

Greek border guards told local newspaper Kathimerini that the project had a huge impact on the flows of illegal immigrants across the land border. They claimed that illegal arrivals were down by 95%, however, there has also been a sharp spike in maritime crossings of the Aegean Sea. In the first semester of 2012, police and coast guard officers in the region detained 102 undocumented migrants, while 1, 536 were intercepted in the three months following the completion of the fence.

Bulgaria follows suit

Bulgarian authorities have found themselves in a similar situation since the beginning of the Syrian conflict. In a seven-fold increase since 2012, about 10, 000 migrants, two-thirds from Syria, have arrived so far this year, leaving authorities helpless to curb the tide or offer basic amenities to those arriving. Speaking to The Economist, one refugee called the situation in Europe’s poorest member state a 'nightmare.' Food and medical attention for the war-torn refugees are scarce and holding facilities squalid.

Like the Greeks, the Bulgarians hope the fence will provide some respite. The fence will span roughly 30 kilometers of the country’s 274 kilometer border with its neighbor Turkey, in a forested, hilly area where visibility for border patrols is limited. The fence, they say, is also part of a broader effort to deal with the situation, including new reception facilities currently under construction and a few thousand additional police officers to patrol the border.

Greece has also begun sending hundreds of migrants back to Syria, in a move strongly criticized by the UNHCR, the UN refugee agency. Bulgarian officials fret that the surge of migrants is sparking a wave of xenophobia. Skinheads beat up a Bulgarian Muslim on November 9th, mistaking him for a Syrian. Thousands recently protested in Sofia after a shop clerk was stabbed by an illegal Algerian migrant.

25, 000 immigrants drowned

In Greece and Bulgaria, the fences represent a desperate attempt by authorities to gain control over events that are getting out of hand. While officials are understandably worried about providing for refugees with such scarce resources, critics worry that fences are counter-productive. Adrian Edwards of the UNHCR, argues that '[i]introducing barriers, like fences or other deterrents, may lead people to undertake more dangerous crossings and further place the refugees at the mercy of smugglers.'

To curb the rising flows of illegal migrants, the EU has built a set of far-reaching border control and enforcement policies over the past decades, known pejoratively as ‘fortress Europe’ by critics. Many argue that the expensive European bureaucracy is inefficient at keeping migrants at bay, and that this leads to serious human rights infringements on Europe’s borders. Moreover, these policies force traffickers to take ever greater risks. In the last two decades, 25, 000 immigrants have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea according to the International Organisation for Immigration.

Activists say that the criminalization of irregular immigration is inevitably counterproductive in the end and leads to abuse, both by border authorities and the brutal traffickers that migrants entrust their lives to. Refugee rights groups have argued for more channels for legal immigration. In the end, however, it is only by addressing the disruptive situations and wealth inequalities that fundamentally drive migration that Europe can address the root of the problem.