Brits in the Baltics: Kaliningrad's shed soviet skin

Published on

‘Where are you from?’ asks Irina, a wealthy Muscovite, ‘and why are you in Kaliningrad?' She’s right to ask - without a McDonald’s or a stag party in sight, it's an unusual destination

Wedged between Poland and Lithuania, the city of half-a-million was gifted to the USSR in 1945. Built on the ruins of German Königsberg, the Nazi’s ‘bastion in the east’, it has garnered much bad press since perestroika as a grim relic of soviet times. Now a special economic zone within the Russian Federation, Kaliningrad received special favor under the Putin administration: his wife comes from the city. With federal money and oil revenue flowing in, it has benefited from a building boom, and now offers the familiar mix of the trashy and the flashy that has given Moscow a reputation. Nearby beaches sweeten the deal, with old German coastal resorts only now being restored.

Waif-rosexuals

At the branch of trendy chain First Coffee on Victory Square, size zero glamour waifs meet New Russian metrosexuals. The city’s favorite place for people watching, a cappuccino here will set you back a mere 80 rubles (1.84 euros or £1.66), a fraction of Moscow prices. At one table a businesswoman talks frantically about flights to St. Petersburg, at another a yummy mummy has popped in for a quick solo lunch. In the smoky heart of the cafe, several businessmen are locked in conversation. On the outside terrace, a Turkish student meets an Italian friend.

At the branch of trendy chain First Coffee on Victory Square, size zero glamour waifs meet New Russian metrosexuals. The city’s favorite place for people watching, a cappuccino here will set you back a mere 80 rubles (1.84 euros or £1.66), a fraction of Moscow prices. At one table a businesswoman talks frantically about flights to St. Petersburg, at another a yummy mummy has popped in for a quick solo lunch. In the smoky heart of the cafe, several businessmen are locked in conversation. On the outside terrace, a Turkish student meets an Italian friend.

Kaliningrad - a political hot potato with an ice-free port

Kaliningrad is a city with big ambitions. Locals compare it to America, to Australia or to Singapore. It’s a melting pot of nationalities and backgrounds, a political hot potato with an ice-free port. ‘Whenever you ask someone where they come from,’ says Marina, a teacher from Kyrgyzstan. ‘There’s a story. They always say, ‘from here’, but then you ask, and where else?’ After the last German residents were deported in 1946, people came here from across the Soviet Union – often from Central Asia. It is striking how many still choose to come.

Attractions and contradictions

Kaliningrad is not lacking in attractions, yet some of its charm lies in its blatant contradictions. An old German house stands in ruins, dwarfed by soviet blocks, only a few hundred meters from the Fishing Village development, an evocation of old Königsberg in no way true to the original. Just off Victory Square the old Gestapo HQ now houses the infamous FSB. ‘You could only use it for one thing,’ smiles local guide Sergei. ‘Something about the design.’ Down the road the derelict House of soviets presides over a deserted car park, while next door the foundations of the vanished Königsberg Castle are being excavated. Kaliningrad is a confusing mix of the old, the new, the reconstructed and the imagined: of Karl Marx statues, fountains, fierce pensioners and blacked-out Hummers.

Kaliningrad is not lacking in attractions, yet some of its charm lies in its blatant contradictions. An old German house stands in ruins, dwarfed by soviet blocks, only a few hundred meters from the Fishing Village development, an evocation of old Königsberg in no way true to the original. Just off Victory Square the old Gestapo HQ now houses the infamous FSB. ‘You could only use it for one thing,’ smiles local guide Sergei. ‘Something about the design.’ Down the road the derelict House of soviets presides over a deserted car park, while next door the foundations of the vanished Königsberg Castle are being excavated. Kaliningrad is a confusing mix of the old, the new, the reconstructed and the imagined: of Karl Marx statues, fountains, fierce pensioners and blacked-out Hummers.

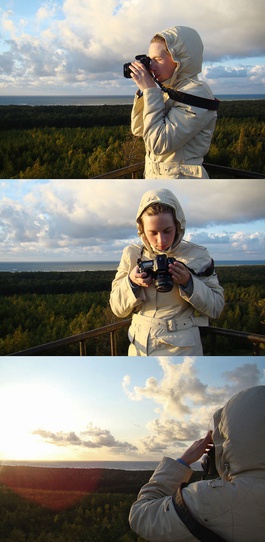

History is turning into business for Kaliningrad, catering as much for local interest as for the hundreds of nostalgic German tourists who visit each year. The museum at the city’s Friedland Gates offers a virtual tour of old Königsberg, while in a bunker by the university you can see the room where the Nazis surrendered the city in 1945. At the restored cathedral, a small museum is dedicated to the memory of Immanuel Kant, buried nearby. To the west of the centre the gentle, bourgeois feel of the old city is tangible in the leafy cobbled streets lined with crumbling turn-of-the-century apartments and villas. The Curonian Spit is the real gem of any visit. It’s a UNESCO-listed stretch of sand in the Baltic, only an hour’s drive from downtown Kaliningrad, more reminiscent of the Sahara than chilly north-eastern Europe. On one side of the peninsula huge empty dunes stretch for miles, while on the other, long beaches prove popular with day-trippers from the city. Densely planted with trees for stability, the Spit is also home to the ‘Dancing Forest’, an uncanny area of woodland where the trees grow with kinks, some are even looped. No scientist can explain the phenomenon.

Back in the city the early autumn sun sheds a soft light on rusting tram tracks and the shady parks seem hardly to have changed for a century. But Kaliningrad is changing fast. As its transformation gathers pace the city’s refreshing dynamism is witnessed only by a small international business set. Brave the speeding minibuses on its bone shaking cobbled streets and see a place where history really happened.

Cheap flights are available to Gdansk (Wizz Air), from where there are daily buses from the main international bus station to Kaliningrad (around £10 - £20 one way), and returns fromthe Kenig-Avto terminal (prices are higher coming back). Buses are rarely full so there's no need to book in advance. It's also possible to travel direct by train from Gdansk, Berlin or Vilnius. Visas and tours can be organised through baltexotic.ru/, or visas can be obtained from a hotel. Rooms at the city's hotel chain are around £40 (44 euro) for a single per night: hotel.kaliningrad.ru/