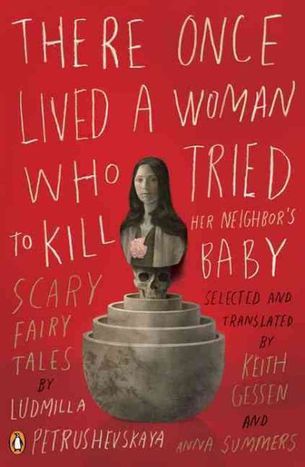

Book review: ‘There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbour’s Baby’ by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

Published on

The renowned Russian writer’s stories begin as they mean to go on – in terse sentences where characters, either stepping out of a provincial newspaper story, or else stepping out of a timeless nightmare, are bound up with a simple, human, horrifying act

‘There once lived a woman whose son hanged himself’. ‘There once lived a father who couldn’t find his children’. ‘There once lived a woman who was so fat, she couldn’t fit in a taxi and when going into the subway she took up the whole width of the elevator.’ ‘There once lived a woman who had a tiny little daughter named Droplet. The girl was just a tiny droplet of a baby, and she never grew.’

From the grim and gripping opening lines in There Once Lived A Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbour’s Baby, published first in the US in 2009, Ludmilla Petrushevskaya unravels a series of modern fables that teeter between bleak realism and bright, perplexing surrealism. As in James Joyce’s Dubliners stories (1914), we slip through streets, and voices, and alcoholic nowhere. Between Moscow and the countryside, lives end abruptly in senseless murders, intelligent cats chew at human bodies and little souls are engulfed in smothering, mauling maternal love.

In one short story, the real terror is that the intruder ‘is not even being careful. Someone isn’t even trying to hide anymore’

Petrushevskaya divides her nineteen stories into four sections – ‘Songs of the Eastern Slavs’, ‘Allegories’, ‘Fairy Stories’, and ‘Requiems’. Each story is short, precise, carefully structured, and yet filled with malleable, asymmetric mutants of horrors, like the two ballet dancers who, in one story, are fused together in a single body. ‘Nina invited me into her house and there I saw strange things,’ reads a sentence of one of the fables. It is with this kind of simple turn of phrase that Petrushevskaya dissects the curiosities she lays out for the reader, leaving for them to decide what is real, what is really strange, and what is warped further by the fairground-mirror perspective of her narrators. In the short story 'There’s Someone In The House', the real terror is that the intruder ‘is not even being careful. Someone isn’t even trying to hide anymore.’

Gnawing disquiet

Petrushevskaya was born in Moscow in 1938. Her short stories have been published for decades, although her work has only recently reached international critical acclaim. Her writing was officially discouraged during the soviet era, despite the fact it is only peripherally ‘political’ in the narrow sense – but its sense of disquiet and gnawing cruelties in Russian homes and lives evidently jutted up against the state’s desire for visions of socialist utopia. Although the soviet censors and style-setters may have taken a dim view to her vision, her stories now are a fascinating key-hole peek through layer upon layer of daily Russian life, where pre-modern myths grow like vines on the sides of urban tower-blocks.

Petrushevskaya was born in Moscow in 1938. Her short stories have been published for decades, although her work has only recently reached international critical acclaim. Her writing was officially discouraged during the soviet era, despite the fact it is only peripherally ‘political’ in the narrow sense – but its sense of disquiet and gnawing cruelties in Russian homes and lives evidently jutted up against the state’s desire for visions of socialist utopia. Although the soviet censors and style-setters may have taken a dim view to her vision, her stories now are a fascinating key-hole peek through layer upon layer of daily Russian life, where pre-modern myths grow like vines on the sides of urban tower-blocks.

As the American translators Keith Gessen and Anna Summers note in the introduction to the Penguin edition of the book: ‘As Solzhenitsyn revealed to the world the insides of the massive prison camps, so Petrushevskaya described for the first time the cramped soviet apartment on the night of a white wedding, the danger not just of sexual failure but also of the mother-in-law barging in drunk.’ Petrushevskaya’s stories can seem so unremittingly bleak, conjuring the kind of senseless, gnawing cruelty of Edward Gorey characters -- an indifferent universe populated equally by torturers and fools – that it raises the question of whether they’re worth reading, what nourishment a reader could get out of all of this. However her skill as a storyteller is to make the rare moments of hope shine even brighter for their rarity, such as in the story of a family who eke out a meagre existence, milky-eyed and trembling, eating mushrooms, dandelions, and consumed in their own thoughts. Petrushevskaya’s stories might often have the plotlines of nightmares, but there is space for dreaming too.

Images: main book cover courtesy of © Penguin; in-text: Ludmilla Petrushevskaya at McNally Jackson book store in New York City, 2009 (cc) David Shankbone/ wikimedia/ David Shankbone official site