Book review Germany: 'degree Facebook internship' generation

Published on

Translation by:

Carol HowardGeneration X became generation Y and the ‘internship generation’ is a recurring topic. However, whichever letters or titles are selected for it, no one can really get a hold on us. Can we really all be lumped together, technically-speaking, in terms of a generation? German writers Manuel J.

Hartung and Cosima Schmitt asked themselves this question in a 2010 book analysing the difficult future of a generation with no name

Anyone who was born in the 1980s belongs to it. These are the people who have been bearing the brunt of all the crises of the most recent past. They were involved in following the collapse of the twin towers on their screens and, as a result of the economic crisis, they have not found a job. They are career martyrs, eternal trainees and, years after finishing their exams, they are still grafting for low pay. Everyone who is now either in higher education or starting their career knows the smell of crisis. But we are not only suffering. In the book statistics abound and leading researchers give their opinions. The reader learns that young people think things over and that students have a political influence. Yet there is a feeling of only being half understood by the authors.

Anyone who was born in the 1980s belongs to it. These are the people who have been bearing the brunt of all the crises of the most recent past. They were involved in following the collapse of the twin towers on their screens and, as a result of the economic crisis, they have not found a job. They are career martyrs, eternal trainees and, years after finishing their exams, they are still grafting for low pay. Everyone who is now either in higher education or starting their career knows the smell of crisis. But we are not only suffering. In the book statistics abound and leading researchers give their opinions. The reader learns that young people think things over and that students have a political influence. Yet there is a feeling of only being half understood by the authors.

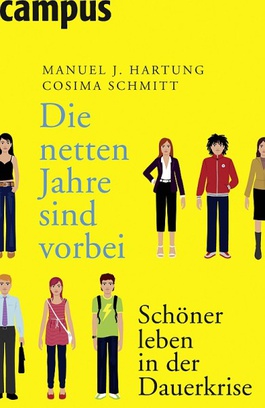

The book ‘Die netten Jahre sind vorbei. Schöner Leben in der Dauerkrise’ (published by Campus in Germany, 2010) translates to The good years are over. Life in a permanent state of crisis is nicer. It's about the ‘bachelor’s degree’ generation, a qualification introduced in recent years in Germany, and describes all Germans joining the labour market shortly before or after they do so. Students and trainees are screened as if with X-ray vision in eight chapters running to 196 pages. It is a book about ‘middleclass children’ which intends to straighten out ‘distorted images’ and to disclose ‘secrets’ about our age group.

‘Dynamic’ generation – not an era

The authors Manuel J. Hartung and Cosima Schmitt state that numerous attempts have already been made to find a name for the young generation. Flurries of headlines have appeared with predictable regularity: ‘facebook generation’, ‘generation X’, ‘traineeship generation’, and so on. They claim that this shows that every headline and every event, no matter how ephemeral it may be, cause the media to put a label on this generation. In the case of eras this might make sense because these are restricted to art, architecture or literature, and the date of their beginning and end can already be given. However, generations are dynamic and diffuse; they do not behave in a controlled manner. The authors understood that as well.

With so many uncertainties, today’s student ought to fall ill: burn-out at the age of twenty-two

Take the typical bachelor’s degree student, for example. The authors state that he is ensnared by the fast-track, module-based degree course which Italians, as well as Germans, are having to cope with. The Italians had to reorganise their system radically as part of the Bologna reforms. However, the authors add that, since the labour market is changing so quickly nowadays, students have to remain flexible, so they have to squeeze work placements into their university holidays as well. The trap for academics is only ensnaring those people who are studying in the same way as before: with a single-minded attitude. The authors write that, with so many uncertainties, today’s student ought to fall ill: burn-out at the age of twenty-two. Yet the authors do not take into account the fact that there are students who have got used to the new university policy and who are pleased about their opportunity to be selective.

Addicted to being a student and towns where earning power is a must

In addition, a glance over the German border shows where German students often congregate – at the universities of their European neighbours. The opening of European borders for university degrees has not only made undergraduates 'addicted to credits and to being a student'. It has linked their choice of degree course to a new factor: earning power. A town has to be able to offer this in order to be chosen as a venue for study. Centres for business sectors, social networks or simply the cost of renting are the reasons often given for being either for or against a town; or the fact that a town’s image is well-liked. For many people, studying abroad only really becomes feasable if tuition fees are taken out of the equation, as they are in France. Unfortunately the authors restrict themselves to Germany, although mobility in respect of a university degree and the precarious situation for new employees have long since been a pan-European recurring topic.

The book also highlights the growing interest of young Germans in politics and democracy as well as the success of NGOs. Yet does this observation go far enough to conclude conversely that ‘we’ have developed into more mature citizens? The reader, who has got used to the style of writing by now (the first person plural form: ‘we’), immediately forgets Germany’s declining turnout in elections and the enthusiasm of its public for depoliticised TV programmes. He believes the sociologist Klaus Hurrelmann, who says that political discourse will increase again.

NGO generation

Instead of putting their faith in the diffuse agendas of the parties and their pragmatic, highly-polished politicians in parliament, the book explains that nowadays young people are getting involved in NGOS in order to help shape the world. The counterargument goes like this: NGOs are frequently described as the fourth business sector these days - they are, above all, a career prospect. But as if that were not enough, another premature incorrect conclusion follows. According to the book, the unabated success of organic labelling in Germany shows that this young generation is increasingly expressing itself by means of its consumer behaviour. This would of course mean that French students are less political than German students, since the French consume far less organic food than their neighbours. The reason for rejecting organic produce in large French towns has more to do with the huge difference in price between conventional and organic food.

The success of organic labelling in Germany shows this young generation expressing itself by means of consumer behaviour

Ultimately the authors do try their best. They predict that a generations-related movement will emerge. The reason, they write, is the inevitable conflict with their predecessors, the babyboomers of the 1960s. This age group had a particularly high birthrate in Germany. The babyboomers will be an unpleasant drain on the pockets of those currently starting their careers, who will then of course be paying into the pension pots. The older generation will soon attempt to get those in power on their side in order to forcibly impose a pension-friendly policy. The authors go on to say that ‘we’ are therefore finally ready to collectively defend our interests for the first time.

This theory is dubious. Generations may exist in the imagination of the German federal statistics office and in calculations by the state, but they are rather unusable as a category when conflicts of interest are concerned. Conflicts like these do not arise at age limits, but in those places where values are negotiated and our values do not always depend on age. Are the authors now to be congratulated because they have managed to characterise a generation? It is certainly nice to rediscover ourselves when reading: ourselves as revolutionaries, as gender-sensitive types. However, we have to defend ourselves against these conclusions. ‘The good years are over’ is a speculation in itself which, in addition, only possesses minimal potential for truth because of its subservience to statistics.

'Die netten Jahre sind vorbei. Schöner Leben in der Dauerkrise’, Campus, 2010

Images: caricature, main (cc) dalechumbley/ Flickr; German book cover ©Campus Verlag; Generation (cc) adamscarroll/ Flickr/ Video (cc) pondscum77/ Youtube

Translated from Generation was-denn-nun? "Die netten Jahre sind vorbei"