Boko Haram: Europe's Navel-Gazing

Published on

Translation by:

Danny S.

Danny S.

The beginning of this year saw one of the bloodiest terror attacks of the century. And we're not talking about France, but rather northeastern Nigeria. Yet compared with Charlie Hebdo, reports over Boko Haram's executed massacre have been reduced to nothing other than footnotes. It's time to look across the Mediterranean.

There can no longer be talk of business as usual in newspapers after the attacks on France. After the mass demonstractions in Paris and razzias (raids) on Muslims in Germany and other European countries, local newspapers have been provided with plenty of material; Europe has been revolving around itself. But the problem in Nigeria is no longer a local matter. Not long after Western media had commented on the situation, the Islamic sect Boko Haram succeeded in expanding its radius of influence to the bordering states Chad and Cameroon; both countries have been forced into military intervention.

Angela Merkel is considering to what extent the EU can logistically and financially support the African strike forces. Even the deployment of a multinational anti-terror unit is in consideration. But the Nigerian population sees itself as largely forsaken. "The international community has not acted with due haste against Boko Haram, compared with how it handled IS and other terror groups", says Odumu. His region hasn't been affected by Boko Haram's brutal attacks, "but every time a region in the North gets attacked, we all feel the pain and danger".

Looking toward where it hurts

"The safety of its citizens may be the government's obligation, but the terror generated by Boko Haram has taken on an overwhelming dimension", says Abraham Sunday Odumu, lecturer for Citizenship Education & Government at the Federal Polytechnic in Kaura-Namoda, northwest Nigeria. That's why the Nigerian government's efforts up until now haven't been enough, he claims. "More proactive measures need to be implemented." The fact remains, that although head of state Goodluck Jonathan wasted no time to publicly condemn the terror attacks in Paris, he has yet to say a word about the massacres in his own country. He seems to be very focussed on the most heated phase of the election campaign, carefully ensuring that the indirect acknowledgement of his impotence in the face of the terror sect doesn't lose him an electoral victory in the upcoming mid-February presidential election.

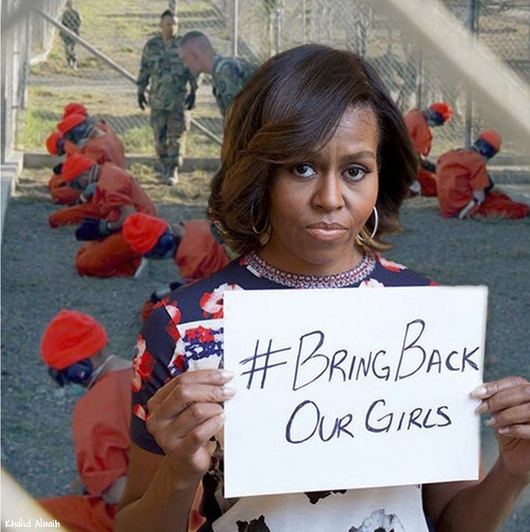

Through his pacifist rhetoric, Jonathan has been sinking in the eyes of not only exiled Nigerians, but also of Amnesty International, who consider "the engagement on the part of the Nigerian government against Boko Haram insufficient," says Christian Hanussek, Nigeria coordinator of the German branch of Amnesty. His words express what many Nigerians feel. The light at the end of the tunnel is dim: Jonathan at least distanced himself last Fall from the unofficial compaign slogan #BringBackJonathan2015, a distasteful play on words of the global online campaign #BringBackOurGirls. Supporters of the campaign demand concrete measures to liberate the girls from Chibok who were abducted by Boko Haram in April 2014. The rage that this slogan sparked among Nigerians reflects not least their bewilderment over the inaction on the part of the government in all things regarding Boko Haram.

Through his pacifist rhetoric, Jonathan has been sinking in the eyes of not only exiled Nigerians, but also of Amnesty International, who consider "the engagement on the part of the Nigerian government against Boko Haram insufficient," says Christian Hanussek, Nigeria coordinator of the German branch of Amnesty. His words express what many Nigerians feel. The light at the end of the tunnel is dim: Jonathan at least distanced himself last Fall from the unofficial compaign slogan #BringBackJonathan2015, a distasteful play on words of the global online campaign #BringBackOurGirls. Supporters of the campaign demand concrete measures to liberate the girls from Chibok who were abducted by Boko Haram in April 2014. The rage that this slogan sparked among Nigerians reflects not least their bewilderment over the inaction on the part of the government in all things regarding Boko Haram.

Yet despite all this, it would be a mistake to believe that only Nigeria's Islamic northern region is affected by grave violations of human rights. With its unresolved murders of journalists, Africa's most populated country ranks at number 12 on the Committee to Protect Journalists' 2014 Impunity Index. Just a year ago, president Jonathan implemented one of the most repressive laws in the world against same-sex marriage. And that's without mentioning issues ranging from police violence, inhumane prison conditions and inadequate state protection for women and children.

Christian Hanussek notes that it's precisely the security forces' violations of human rights that have led to a failed fight against the Islamists. Amnesty International demands that the "Nigerian state protect its citizens from Boko Haram in an orderly conduct and hold perpetrators accountable in court," says Hanussek. "Instead, innumerable people are being arrested by security forces, tortured and murdered. The international community must put pressure on the Nigerian government to fight Boko Haram according to constitutional laws".

In January, German Bundestag President Norbert Lammert called for a moment of silence for the victims of the Paris attacks, "as a symbol of our respect, our condolences and our solidarity". It is pointless to speculate whether the Nigerian victims would have received this same respect, had the massacres of Baga dominated the news at the beginning of January.

The reaction to the attacks on Paris show that the media will not allow itself to be muzzled. But as long as Europe continues to navel-gaze and deliberate overlook the mass murders in Nigeria, it makes an insufficient use of its vaunted freedom of press. Maybe it's time to borrow an overworked slogan from the Ferguson protests in America and bring #NigerianLivesMatter out on the streets. At least that would be a start.

Here you can read Part 1, Boko Haram: The Massacre in Charlie's Shadow

Translated from Boko Haram: Europas Nabelschau