Black gold: Equatorial Guinean oil for Europe

Published on

Translation by:

Gemma TurnerFrom 29 June to 3 July, the 19th World Petroleum Congress takes place in Madrid is attended by representatives from governments across the world, oil companies and international organisations

Whilst energy leaders discuss the future of the industry in Madrid, the price of a Brent barrel has risen past 130 dollars. On top of this the food shortage crisis threatens to last until 2010, putting the underdeveloped countries in a difficult position. The EU and other main international donors are offering fewer solutions.

Political and business leaders are meeting to discuss the 'challenges for the industry in a changing world.' They want to assure a 'continued, economically viable and stable supply that will satisfy the societies needs in a sustainable, transparent, ethical and environmentally friendly way.’ It is a wordy declaration of intentions which are far from the reality of the relationships between the countries that produce oil and those that import it. The countries that produce oil, in the most part, belong to the group of underdeveloped countries.

African oil

75% of the oil used in Europe comes from outside Europe. Almost 19% of this is imported from Africa. Although the oil producing potential of central Africa represents a maximum of 1.6% of the world’s reserves, their strategic interest is invaluable given the endemic instability of the Persian Gulf. The crude oil from the Guinean Gulf is easily accessible and is low in sulphur, thus easy to refine.

In fact, the main export to the EU from five of the seven countries that make up the Central African region (Cameroon, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea), is oil. In particular, crude oil represents 88% of Equatorial Guinea’s exports to the EU.

Contradictions in the EU

The EU cannot pursue its energy interests and be a world figurehead for international help and development. The new contenu treaty puts an end to the system of non-reciprocal commercial arrangements. It will allow the developing countries that signed the agreement to introduce their commercial produce into the EU without having to pay customs tax. Above all, they won't have to offer the same advantages as the European products. Due to this, the signing of the new economic collaboration agreements between the EU and six other regions (mainly ex European colonies or territories), will put an end to a model of cooperation that has converted the European Union into a world figurehead for international help and development.

The EU cannot pursue its energy interests and be a world figurehead for international help and development. The new contenu treaty puts an end to the system of non-reciprocal commercial arrangements. It will allow the developing countries that signed the agreement to introduce their commercial produce into the EU without having to pay customs tax. Above all, they won't have to offer the same advantages as the European products. Due to this, the signing of the new economic collaboration agreements between the EU and six other regions (mainly ex European colonies or territories), will put an end to a model of cooperation that has converted the European Union into a world figurehead for international help and development.

Another priority for Europe is to diversify their oil provision; they are looking toward Africa. However,Africa was not even mentioned in a green book published by the European commission in 2000, called ‘Towards a European strategy for the security of energy supply’. The continent of Africa was left for development discussions instead.

So, when the EU decided to approach its energy relations with the continent, it did it by launching the ‘energy initiative for poverty eradication’ during the world summit for sustainable development in Johannesburg (2002). Aalong general lines, this initiative claimed to bring electricity to rural zones. However it did not deal with the central problem of the conservation of the oil reserves of underdeveloped countries such as Equatorial Guinea by sustainable human and economic development.

Europe forgets the Equatorial Guineans

In Equatorial Guinea - the only Spanish speaking country in Africa - the per capita income has risen (thanks to oil) to 13, 167 euros (20, 510 dollars), one of the highest rates in the world. However, in this small central African country, life expectancy is as low as 43 years, 44% of the population do not have access to drinking water and the majority of the population, especially the 61% that live in rural areas, live in poverty. It is hardly surprising then, that this country comes 127th out of 177 countries in the human development index produced by the UNDP (United Nations development programme).

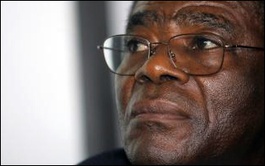

In Equatorial Guinea, only president Teodoro Obiang and his family (who control the interests of the administration and monopolise the country’s most profitable dealings), benefit from the income from oil, which makes up around 94% of the country’s GDP. However in May 2008, Teodoro Obiang retained his presidency by winning the elections with a surprising majority of almost 100% of the votes.

In Equatorial Guinea, only president Teodoro Obiang and his family (who control the interests of the administration and monopolise the country’s most profitable dealings), benefit from the income from oil, which makes up around 94% of the country’s GDP. However in May 2008, Teodoro Obiang retained his presidency by winning the elections with a surprising majority of almost 100% of the votes.

Whilst the continuance of a regime discredited by the international community seems to be assured, many of the EU countries led by France and Italy have recently decided to withdraw the aid promised to these poor countries. This means abandoning the objective of reaching aid equivalent to 0.7% of the European GDP before 2015. But what will happen now to the people of Equatorial Guinea if their biggest commercial partner and aid giver no longer wishes to participate in the distribution of black gold?

Translated from Europa quiere petróleo ecuatoguineano y punto