Between Football and Citizenship: The Strange Case of the Oriundi

Published on

Translation by:

Kait BolongaroIn the tradition of oriundi of the Italian national football team is almost a century old, but not without controversy. However, there are 'B league' oriundi, the foreign-born children of Italian immigrants who share the culture and identity of the country of their parents but have forever lost the right to Italian citizenship.

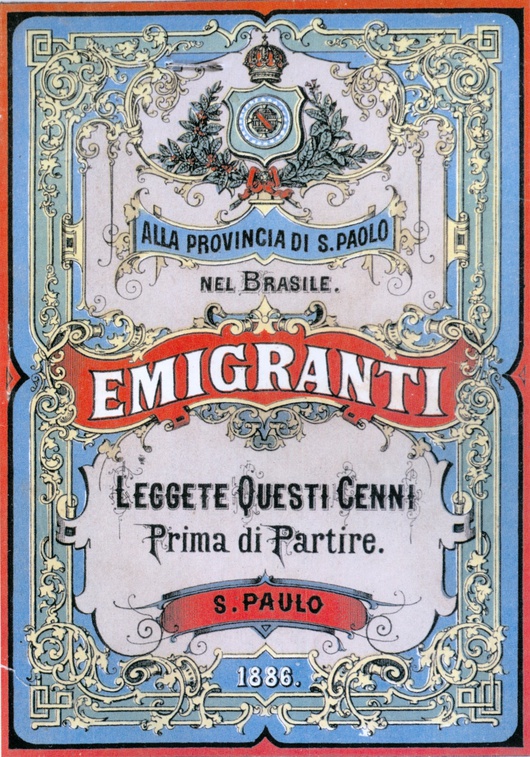

The Brazilian World Cup will be remembered as the tournament of double nationality. In a competition where there are at least 274 players with two passports, the football market virtually depends on the transfer of players from one team to another, within the no longer clearly defined borders between jus solis, place of birth, or jus sanguinis, blood line. In Europe, it is often the case of footballers, children of second or third generation immigrants; consider the national teams of Switzerland, France (Black, White and North African), Germany, Holland and Belgium.

However, Italy is different. In this case, the concept of oriundi comes into play. The term is derived from Latin and refers to foreign-born players who are given Italian nationality through an often-distant Italian ancestor. Today, Prandelli said that the oriundi are the new Italians, mentioning Gabriel Paletta and Thiago Motta as examples. However, over their history, the Azzurri have included at least 42 of these players on their roster, half of whom were Argentinean: beginning in the 30s with the quartet of Attilio Demaria, Enrique Guaita, Luis Monti and Raimundo Orsi to Juan Alberto Schiaffino, Omar Sivori, José Altafini and finally with Mauro German Camoranesi, part of the team who won the World Cup in 2006.

As Paolo Conte sings about South America: “the man who has come from far away has the genius of Schiaffino but religiously touches bread and watches his Uruguayan stars. Ah, South America ...” But what if the person doesn’t have the football genius of Schiaffino? The question arises because there are cases that are diametrically opposed to the Uruguayan champion, where the rules simply do not allow the nationality, once lost, to be recovered, regardless of how close the Italian ancestor is. In other words, if you can’t provide a stellar performance in football, any request for the nationality will be rejected. A nationalist slogan reads: “Nationality – if you don’t inherit it, you have to merit it, but can’t be given it.” Is playing good football the true marker of merit? What about the other potential Italians who aren’t lucky enough to be superstars?

As Paolo Conte sings about South America: “the man who has come from far away has the genius of Schiaffino but religiously touches bread and watches his Uruguayan stars. Ah, South America ...” But what if the person doesn’t have the football genius of Schiaffino? The question arises because there are cases that are diametrically opposed to the Uruguayan champion, where the rules simply do not allow the nationality, once lost, to be recovered, regardless of how close the Italian ancestor is. In other words, if you can’t provide a stellar performance in football, any request for the nationality will be rejected. A nationalist slogan reads: “Nationality – if you don’t inherit it, you have to merit it, but can’t be given it.” Is playing good football the true marker of merit? What about the other potential Italians who aren’t lucky enough to be superstars?

A five year window to reclaim your nationality

While the decades old oriundi tradition continues to serve Italy well during international football competitions, it has become the bane of existence for the descendants of more recent Italian immigrants. Somehow, it is easier for a football player with a great-great grandfather from Italy to become a citizen than it is for the children of thousands of Italians who migrated after World War II.

After 1945, as immigration laws hardened, many migrants were encouraged or forced to naturalise in their adopted country to remain there without a visa. Many of those who migrated before weren’t under such an obligation. Before 1992, dual citizenship was not recognised in Italy, meaning that any migrant who naturalised automatically lost their citizenship.

When the law changed, there was a five-year window to regain citizenship – but the government didn’t bother to tell any of its ex-citizens. No phone calls, letters, telegrams. In the prehistoric age without Internet, this meant that most weren’t aware that they could even get their citizenship back. Instead of retroactively decreeing that all former Italians could stop by the embassy to pick up their passports at their convenience in the future, i.e. no time limit, which would have saved a lot of hassle and heartbreak, the government decided that this limit was ample time to find out about the repatriation project.

This strategy backfired and has left the children of Italians, who often speak the language and share the culture of their parents, without any recognition of their Italian-ness. Laura D’Amelio, an Italian-Canadian, shares her experience on having her application for Italian citizenship rejected despite her strong family, cultural and linguistic ties to Italy.

No official recognition from Italy

“For the longest time, I assumed I was Italian. All four of my grandparents were born there, my parents were born there and every extended relative I know was pretty much born there. Except for me,” she writes. “When I went to claim my Italian citizenship a few years ago though, I was denied. Apparently there was this five-year window when Italian-Canadians could claim dual citizenship that I missed when I was young. I was, and am, upset.”

“For the longest time, I assumed I was Italian. All four of my grandparents were born there, my parents were born there and every extended relative I know was pretty much born there. Except for me,” she writes. “When I went to claim my Italian citizenship a few years ago though, I was denied. Apparently there was this five-year window when Italian-Canadians could claim dual citizenship that I missed when I was young. I was, and am, upset.”

The only path for citizenship for D’Amelio now is to reside in Italy for 10 years which would mean navigating a bureaucratic nightmare, marrying a current Italian citizen for 2 or 3 years, or work for the Italian government, such as in the armed forces, for five years. D’Amelio decided that she didn’t need the papers to prove she was Italian.

“To be told you aren’t Italian, when you always thought you were, is strange and confusing. It led me to the thought of who decides your culture or how your life is to be led? Those who issue passports or those who live it. I may not be able to live there freely, or be a “card-carrying” Italian. But I am Italian. I’m here to explore what my Italian life is – how I live it and who I am.”

The concerns and worries of people like Laura D'Amelio remain. If tomorrow you would like to prevent a tragedy like this from happening to your child, it may be a good idea to enroll him or her in an excellent football school and hope that he becomes a champion. Only then will they have a passport emblazoned with the words Italian Republic.

Translated from Lo strano caso degli oriundi, tra calcio e cittadinanza