Berlin's multicultural music mix: subsuming Berlin

Published on

Street art like Welcome to Schwabylon is everywhere in Berlin. Schwabylon was originally coined in 1973 as a name of a huge Munich shopping mall which proved unsustainable - much like the concept behind another word the Germans invented in the 70s: multikulti.

Attempts to build a multicultural society ’utterly failed’, Angela Merkel surrendered in 2010 – but she surely wasn’t referring to one of the most exciting and progressive music scenes in Europe

In Berlin the party never stops. The city is vibrant, easy-going and full of interesting people. No one cares how you look and where you come from. ‘Cheap rent’ are magic words. Apparently, that's all creativity really needs. So who comes here these days and why? ‘Everyone who can, really,’ says Berlin-born DJ/producer of Bulgarian origin Stefan Goldmann. ‘Mostly you see two groups: middle class kids with some backing from their parents, and to a lesser degree, people from societies’ fringes. The first group moves in because they heard it is a party. The latter because it’s some place in the west. The astonishing thing is that you don’t feel the difference as long as you are around middle class people. They all speak English, dress the same way, listen to the same kind of music and totally pretend they have no culture different from anybody else’s. So there is not much noticeable cultural influence of migration.’

Multiculturalism 1994: when it was OK

German-Turkish DJ Ipek Ipekcioglu's career took off in an unwillingly caustic way. ’The promoter of the club asked me if I was a lesbian and Turkish, before begging me to DJ, the next three days we're having a queer oriental party and we don't have a Turkish DJ. I didn't know how it worked, I only had tapes. It had never crossed my mind to be a musician or a DJ.’ This was back in 1994 when the idea of multiculturalism and the so-called 'cultural quotas' did Ipek a favour. For a while she was the only one who played non-American music on the scene, with Turkish, Middle Eastern and Arabic sounds in her sets that later mixed with a electro. Today she is internationally sought after and acclaimed as one of Berlin’s most important cultural contributors. We meet in a street cafe between gentrified Kreuzberg and Neukoln (and FYI - it is not cool to call it Kreuzkoln anymore). On her living room table there is a DVD called Tokyo Godfathers, on her wall - some Indian posters and a huge photo of Istanbul. ’Sometimes it's hard to come out of the ethnic cliche, as I also do electronic stuff,’ she says. ‘People ask for ‘some Arabic' and I say 'But this IS Arabic'. It's just not what they're used to. Often people want the traditional things, but you have to teach them new sounds or find yourself other scenes.’ Ipek's rough estimate is there are five or six like her, so she is always looking around, willing to support newcomers playing ethnic stuff.

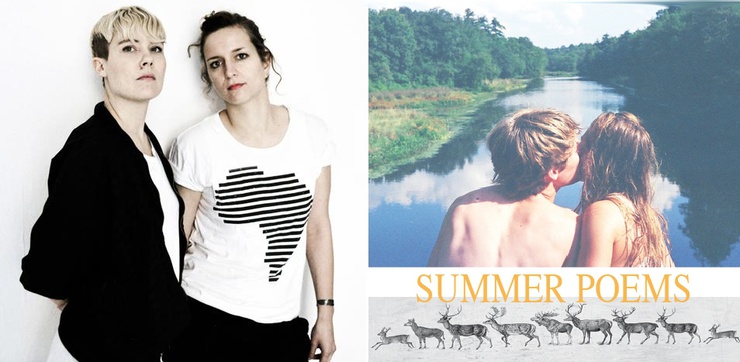

In general, music scenes like Balkan beat don't seem to mix. ‘They have nothing to do with the Berlin sounds, it just gets played. People lead parallel lives,’ says Berlin-based Frenchman Théo Lessour, author of the book Berlin Sampler. Stefan thinks that it’s only with the long-rooted minorities that you feel an influence on the population and music. This is why most Germans have some idea what ‘Turkish pop’ is. Others fill in slots that have been around through media and record distribution, like reggae. Sometimes there are breakthrough moments, like Nordic By Nature. The two Swedish girls promote Scandinavian music in Germany, DJ, have their own radio show on BLN.FM and organise concerts and parties such as the Berlin midsummer festival.

In general, music scenes like Balkan beat don't seem to mix. ‘They have nothing to do with the Berlin sounds, it just gets played. People lead parallel lives,’ says Berlin-based Frenchman Théo Lessour, author of the book Berlin Sampler. Stefan thinks that it’s only with the long-rooted minorities that you feel an influence on the population and music. This is why most Germans have some idea what ‘Turkish pop’ is. Others fill in slots that have been around through media and record distribution, like reggae. Sometimes there are breakthrough moments, like Nordic By Nature. The two Swedish girls promote Scandinavian music in Germany, DJ, have their own radio show on BLN.FM and organise concerts and parties such as the Berlin midsummer festival.

Vladimir Kaminer was also pretty successful with his Russendisko events, but that only went so far, says Stefan. 'People used to get wasted on vodka and dance to Vysotskiy – but that was about it.’ Still, he thinks when the music is really good it stays within ethnic ghettos. 'If Germans ever get to hear gypsy music it’s all brass bands from Romania,’ he explains, ‘but never the synth stuff gypsies listen to in their own bars and clubs. It’s all there, but that’s totally under the radar.’

Faraway, so close

Ethnic influences in music are too often simply used as a spice,’ says Andreana Slavcheva, former editor of online radio service Aupeo.com. ‘DJ don't really care about the essence.’ She thinks it is mostly an attempt to be creative, exotic or original. To confirm her theory, Theo Lessour tells me about a party he recently went to: 'The guy played only Malian tapes from an African label of the 80s. He was white and most of the people were white, there aren't many Africans in the city anyway. It was a fun hipster party with cheap African music made with bad equipment.’

'There is no social pressure to make it in Berlin. It's a little island where you can believe for a while that capitalism is not eating you every day'

On the other hand, Goldmann's latest techno track employs motives (that were not sampled, but composed and played by him) in the style of the very popular and much despised Balkan/ Bulgarian/ Turkish low-brow pop-folk genre aka chalga. ’The world is more than ready for chalga,' he says. 'I’ve played it anywhere from Italy to Japan. In Sofia, the ice is melting too. I played it on new year’s eve at Kino Vlaykova and people just started getting how awesome the whole thing is. It is the modern electronic music that comes from there, that no one in Berlin or New York or London can compete with so far. The potential is so massive in terms of modernity. I can occupy that.’

Make it in Berlin

Tim Thaler, co-founder and editor-in-chief of radio station BLN FM and professor of journalism, is at the charming slightly run-down Mitte apartment that the radio is housed in. We sit on the pavement outside, where we are soon joined by radiant and intimidatingly experienced DJ/booker/promoter Barbara Hallama, who is passing by on her bike. ‘I don't think i have seen a musician or a DJ make it in Berlin,’ he says. ‘They move here, they try to make it for a year, they see it's not working and they go back.’ Radical escapism is the essence, Theo concludes. 'There is no social pressure to make it. It's a little island where you can believe for a while that capitalism is not eating you every day, you can sneak out. People here believe they live differently.’

With 50, 000 DJs in town, the club circuit is impossible to get into unless you know insiders. Gigs in small bars are also extremely hard to get and also absurdly paid, if at all. You can start your own party, but it's not going to work either, according to Tim. It takes serious self-discipline to stay focused, as Ex-Berliner magazine's music editor David Strauss stated in a radio show on Spark FM: ’My intellectual ambitions have been subsumed by my Berlin-ish desire to merely get by.’

This article is part of the seventh edition in cafebabel.com’s 2012 feature focus series on multiculturalism in Europe. Many thanks to the team at cafebabel.com Berlin

Image: main © courtesy of Ipek Ipekcioglu official facebook page; in-text courtesy of © Berlin Sampler; © Nordic By Nature official page