Berlin film festival: 60 years of masterpieces

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah TruesdaleThe Berlin international film festival (or Berlinale) has been fraught with political struggles. Created by the allies of west Berlin right under the noses of communist dictators, it was a way of opening a window to the 'free' world. Over the years, it has developed into an unmissable world cinema event

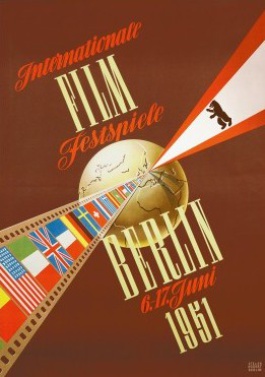

It didn’t take long for the Berlinale to become an arena for ideological debate. It was English filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock who, in 1951, inaugurated the first festival and so firmly anchored it in western European and American cinema tradition. When Willy Brandt, the mayor of Berlin at the time, gave the opening speech of the festival in 1958, he underlined its importance as a symbol of a tolerant city, open to the world, in opposition to the communist behemoth. Several days later Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the soviet union, presented an ultimatum to the allies to leave west Berlin. It wasn’t until the 1960s, when the festival was privatised (until then, it was in the hands of the west German government), that it was opened up to Europe and the east, but still not without some tensions.

Cold war

The controversy marked by the cold war didn’t stop there. In 1970, O.K., a Michael Verhoeven film which portrayed the rape and murder of a young Vietnamese woman by American soldiers, caused a scandal and led to the festival being cancelled. Even so, the jury dared to award him the Golden Bear, which was considered by some of the organisers to be unforgivable. In 1979, The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino) delivered a critical examination of communist Vietnamese society: the film went down badly in communist states, and some boycotted the festival. The Berlinale was also the scene of disputes between communist states: Der Aufenthalt ('The Turning Point', 1983) by Wolfgang Kohlhaase, which portrayed German prisoners in Polish camps immediately after the end of the war, was pulled from the festival by east Germany after protests from the Polish.

The controversy marked by the cold war didn’t stop there. In 1970, O.K., a Michael Verhoeven film which portrayed the rape and murder of a young Vietnamese woman by American soldiers, caused a scandal and led to the festival being cancelled. Even so, the jury dared to award him the Golden Bear, which was considered by some of the organisers to be unforgivable. In 1979, The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino) delivered a critical examination of communist Vietnamese society: the film went down badly in communist states, and some boycotted the festival. The Berlinale was also the scene of disputes between communist states: Der Aufenthalt ('The Turning Point', 1983) by Wolfgang Kohlhaase, which portrayed German prisoners in Polish camps immediately after the end of the war, was pulled from the festival by east Germany after protests from the Polish.

As well as being the location for ideological disputes, the festival has supported an artistic, provocative avant-garde. The 'new wave' of directors in the sixties which pushed aside cinematographic conventions, seeing them as narrow categories that had had their heyday, was a feature of the festival. So, French-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard received the Golden Bear in 1960 for À bout de souffle ('Breathless'), which introduced new narrative standards. Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni was honoured for his film La notte (1961), as were German directors such as Werner Herzog, winner of the Golden Bear in 1968 at the age of 26 for Lebenszeichnen ('Proof of Life') and president of the jury that year, or the incontrovertible Rainer Werner Fassbinder for Die Ehe der Maria Braun ('The Marriage of Maria Braun').

This defence of the avant-garde was also apparent in 1976 when Ai no corrida ('In the Realm of the Senses') by Japanese director Nagisa Ôshima was banned in several countries but shown during the festival. Partway through the first screening, the reel was confiscated by the German police because of its 'pornographic' content. Since the Berlinale is celebrating its 60th birthday, it will be showing a selection of these masterpieces mentioned above, including Akira Kurosawa’s Ikiru (Doomed, 1952) and Central do Brasil ('Central Station', 1998) . As could be expected, the festival’s producer has decided not to show O.K.

Translated from Berlinale: 60 ans de cinéma et de politique