Berlin - breakwater of nostalgia

Published on

Translation by:

Ed SaundersThe death and rebirth of two city icons provide an impressive picture of the nostalgia that characterises Germany

In one of the short breaks the clouds allow the tourists, a group of Chinese visitors pose for classic tourist snaps in old East Berlin. Whether at the feet of the statues of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, or in the garden between the administration building and the Karl-Liebknecht-Straße, the photographer tries out all possible poses, interspersed with gestures of annoyance. He gets increasingly dissatisfied with the setting of the photos: there is no way of hiding the ghostly image of an outsized building which looms like a corpse behind both the historical statues. This is the Palast der Republik (Palace of the Republic), once the former seat of the parliament of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the German communist regime, which until 1989 was under Soviet control.

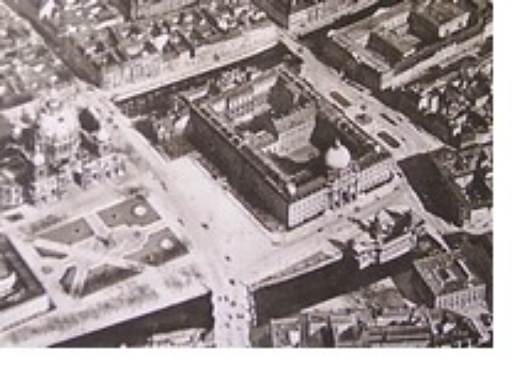

The dictator Erich Honnecker opened the Palast der Republik on the ruins of the historic Stadtschloss (City Castle or Palace) in 1976, once the palace of the Prussian Kaiser. The palace ‘served not only as the seat of the Volkskammer, the GDR parliament, but also housed a palace of culture, complete with concert hall, theatre, restaurants and various exhibition spaces and cafes, all of which was free for all. A real meeting place,' explains Alexander Schug, a 33-year-old German historian. The building, together with the omnipresent television tower, 300 metres high on the other side of the garden, forms an imposing architectonic interplay and a landmark that wanted to present an image of modernity and progress. This was the image that the Marxist German regime wanted to show the world. The new palace united all the luxury of the architectonic avant-garde and interior design of the seventies. Nevertheless, it already bore the contaminated seeds of a disease difficult to overcome: asbestos.

The dictator Erich Honnecker opened the Palast der Republik on the ruins of the historic Stadtschloss (City Castle or Palace) in 1976, once the palace of the Prussian Kaiser. The palace ‘served not only as the seat of the Volkskammer, the GDR parliament, but also housed a palace of culture, complete with concert hall, theatre, restaurants and various exhibition spaces and cafes, all of which was free for all. A real meeting place,' explains Alexander Schug, a 33-year-old German historian. The building, together with the omnipresent television tower, 300 metres high on the other side of the garden, forms an imposing architectonic interplay and a landmark that wanted to present an image of modernity and progress. This was the image that the Marxist German regime wanted to show the world. The new palace united all the luxury of the architectonic avant-garde and interior design of the seventies. Nevertheless, it already bore the contaminated seeds of a disease difficult to overcome: asbestos.

Like sharks hunting

I am convinced that we will be able to present a completely new Prussian imperial palace to the public by 2017,’ says Lür Waldmann enthusiastically, without batting an eyelid and with messianic zeal. A 52-year old lawyer, he is the textbook German of yore – like Odín, the chief god in Norse mythology - big, blonde, blue-eyed and powerful. With the strong gestures he makes, he seems to have come straight from the Valkyrie myth. He is supporting the full reconstruction of the Stadtschloss in Berlin, after the gradual destruction of the Palast der Republik is complete. In April 2003 the Bundestag decided the asbestos should be removed and the palace dismantled. The question is how the space freed up should be used in the meantime. Increasingly diverse ideas and projects are being proposed.

I am convinced that we will be able to present a completely new Prussian imperial palace to the public by 2017,’ says Lür Waldmann enthusiastically, without batting an eyelid and with messianic zeal. A 52-year old lawyer, he is the textbook German of yore – like Odín, the chief god in Norse mythology - big, blonde, blue-eyed and powerful. With the strong gestures he makes, he seems to have come straight from the Valkyrie myth. He is supporting the full reconstruction of the Stadtschloss in Berlin, after the gradual destruction of the Palast der Republik is complete. In April 2003 the Bundestag decided the asbestos should be removed and the palace dismantled. The question is how the space freed up should be used in the meantime. Increasingly diverse ideas and projects are being proposed.

One of these projects is called ‘We’re building the Schloss’, an initiative set up by Waldmann and an anonymous investor, who is donating ‘500 million Euros for the purpose of reconstructing an identical replica of the Stadtschloss – a pure Stadtschloss,’ as one of the numerous brochures says. ‘Everything is being done with the purpose of making the Kaiser’s residence understandable and accessible. We’re planning to integrate into the Schloss a gallery with shops, as well as a hotel and restaurants’. Very solid then, but not overly so. The government must first grant permission for the lease of the area, and give away the licence for such an initiative, which ultimately only serves pure commerce.

One of these projects is called ‘We’re building the Schloss’, an initiative set up by Waldmann and an anonymous investor, who is donating ‘500 million Euros for the purpose of reconstructing an identical replica of the Stadtschloss – a pure Stadtschloss,’ as one of the numerous brochures says. ‘Everything is being done with the purpose of making the Kaiser’s residence understandable and accessible. We’re planning to integrate into the Schloss a gallery with shops, as well as a hotel and restaurants’. Very solid then, but not overly so. The government must first grant permission for the lease of the area, and give away the licence for such an initiative, which ultimately only serves pure commerce.

‘The project will finance itself, and will save the government a lot of money’, Waldmann argues, ‘but at the moment, members of parliament of all parties are telling me that the land isn’t for sale.’ At the moment, the signs are not pointing to privatisation.

All this, in spite of the fact the German administration is not poor and the Berlin Senate will, in all likelihood, shell out 480 million euros to realise its own project: the construction of the so-called Humboldt Forum, a museum presenting the work of the Humboldt brothers, and showcasing the historic scientific collections of the Humboldt University and the Museums of non-European Cultures. If this plan is realised, only the main facade of the old Berlin Stadtschloss will be restored. The money for it – a futher 80 million euros – would then go to a special patron of another organisation: the Berlin Schloss Society. They would receive support, thanks to main sponsor Wilhelm von Bodin, a prosperous Hamburg businessman. ‘We aren’t making fun of the project,’ says Waldmann. ‘But we don’t feel it’s necessary to give so much space over to a few masks from Africa or Japan, that could be exhibited just as well in Paris or other European cities.’

Nostalgia like a loaded gun

Often the most nostalgic people are those who want to preserve the symbols and places of the communist regime. Like the union of young Berlin architects, the self-designated saviours of the palace, who want to overcome the ideological ‘Palace or Schloss’ conflict. They criticise the enormous costs incurred by both the private and state projects in building the Schloss (about 800 million euros). They propose preserving and using the palace as it is – a multifunctional building. ‘We can’t even afford a symphony orchestra, let alone a Stadtschloss,’ they say.

‘The people who want the Schloss are all fascists’, says Hannes, balancing a cigarette between his lips, whilst sitting in the kitchen of Oppelner Straße 42, in the heart of Berlin’s bohemian Kreuzberg district. It is the opinion of a student of political science with the assured tones of a rich son. An opinion in contrast to which, as Schug maintains, ‘as a historian you should remain neutral. So my work is historical review. What I think is a shame is the loss of an architectonic inheritance of a Prussian palace in the middle of the city, with all the militaristic reminiscences it brings with it.’ Schug has compiled a history of the Palast der Republik, together with history students Arne and Jan from the Humboldt University, for an exhibition in the Prenzlauer Berg Museum. They will now start to build a ‘historical archive of the building’.

Is only tourism king?

What reasons are there then to rebuild the old Schloss? ‘When I walk through Berlin, I see hugely diverse modern buildings. Within five minutes I know how they’ve been constructed,’ Waldmann continues his idea. ‘I could look at the Stadtschloss for hours, though, without getting bored, in the same way I could look at Versailles for hours.’ It sounds strange, but Waldmann does not consider himself to be nostalgic, quite the opposite. Frank Freiherr von Coburg is responsible for the ‘We’re building the Schloss’ organization’s communications. He explains caustically, ‘This doesn’t have anything to do with longing for kings or Kaisers of the past. Our project is solely aimed at the goal of attracting more tourists.’ A statement confirmed by Daniela Urbschat. The renowned art-photographer from Berlin, who has done photoshoots with figures like Queen Noor of Jordan and King Juan Carlos I of Spain, explains, ‘As a partner in the Waldmann initiative my support is based upon improving the city’s image, with the aim of getting people talking more about Berlin.’

Those who want to see and understand what the Palast der Republik was once like, have to content themselves with a visit to the GDR Museum. Demand for it is not that high – imagine a museum of Francoism in the middle of the important central Plaza de Colón, next to the principal avenue in Madrid.

Those who want to see and understand what the Palast der Republik was once like, have to content themselves with a visit to the GDR Museum. Demand for it is not that high – imagine a museum of Francoism in the middle of the important central Plaza de Colón, next to the principal avenue in Madrid.

In-text photos: Palast der Republik and tower (Jonas/ Flickr), Marx & Engels statue in Berlin's centre, Lür Waldman, de-asbestos-ing, Old Berlin panorama (FNS)

Translated from Berlín, el rompiente de las nostalgias