Badante: the ghosts of Italian society

Published on

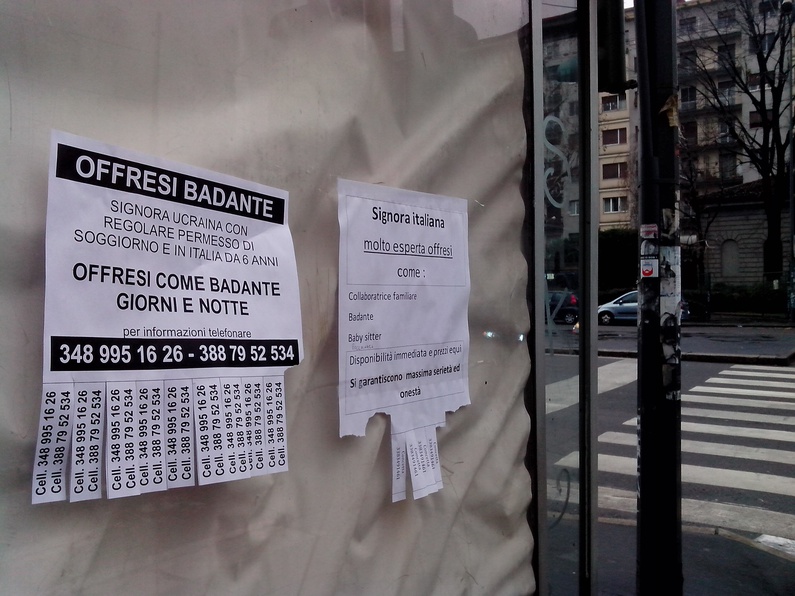

In Italy, they call them "badante" - female caregivers. While these women do essential jobs, ultimately they are exploited. Without labour rights and isolated from Italian society, they represent the growing feminisation of low-skilled migrant work.

The few people who know her in Italy call her Claudia. This 59-year old decided to spontaneously go abroad in the 90s after suffering financial difficulties in Bulgaria. She contacted a representative of an agency that mediates between families abroad and women from Bulgaria.

Before her departure, the company charged each person migrating 920 euros - a fortune in the 90s. The agency man also took their passports and kept them for an initial period. By such methods, the agency “secured” the women’s acceptance of the original arrangement. Given the women’s contracts went through the agency, they could pass on illegal charges many employed women each month.

When she arrived in Rome in the 90s, neither did Claudia know any foreign languages, nor had she ever previously cared for the sick or elderly. For many years she worked as an economist in a large company in Bulgaria.

We are talking while travelling on a train towards Florence. She is burdened with two giant bags full of gifts (including expensive Italian chocolates) and has to transport them to a driver in the city, who would then would travel to Bulgaria and deliver them to Claudia’s children and grandchildren. It is a complex transmission that could easily be replaced by courier, but Claudia prefers it this way. She sends money every month to her two older sons, who already have families and children.

"But they are already independent and mature people. Why do they still rely on you?" It’s a question that’s right on the pulse. Claudia tells me that this sometimes happens with mothers, especially with the Bulgarian ones.

Over the years, Claudia has taken care of different people in several Italian cities. Her first job was to care of a sick elderly woman. She was shown only once how to transfuse blood by the old woman’s daughter, who was a medical officer. Her duties involved this procedure on a routine base, as well as making injections, washing her patient, cooking, and cleaning the house.

After many years she managed to separate herself from the company, which initially transferred her to Italy – something, which is usually a very difficult step because such companies are notoriously protective of their income – the fees they charge people like Claudia.

Now, Claudia works for herself. However, she does not know what kind of pension she’ll receive in the near future.

Badante boom

The number of foreign domestic workers in Italy - almost all of them women - has been increasing in recent years. At present, they exceed 1.3 million people. It seems the latest government measures to regulate illegal immigration are still insufficient.

The so-called “badante” – carers of the elderly or domestic workers – come mainly from Eastern Europe: such as Romania, Ukraine and Moldova. Despite the large number of Bulgarians, their presence remains relatively small compared to those who come from other countries in Eastern Europe. A large proportion of these badante have a good level of education and skills acquired in their countries of origin. They often choose to have fewer qualifications, for even higher-skilled jobs aren’t well paid in their home countries.

Domestic workers in countries such as Italy fill holes in the health and social system. According to Antonino Ferara, a young Italian who works as an assistant in the NGO sector on projects related to regional Labour Agency, which support the integration of immigrants, this is a kind of “private” health system organised within the national health system. At his work he has met many “badante” from Eastern Europe. He also believes that term should be substituted with neutral terms like “domestic workers”.

Ethical issues

Antonino tells me that there are ethical issues that must be considered, starting with the fact that the emancipation of Italian women is in turn associated with the hard work of foreign women arriving in the country, having taken the decision to divide with their families.

In addition, there are psychological risks, such as the plain fact that the patients for whom the badante care for may die. These women depend strongly on the physical and psychological condition of the patients, which may impact their psychological condition.

These women do not feel that they live in a community, they are mostly “alone“. This is due to their working rhythm – they must provide “continuous” care for the elderly. They provide support in all aspects of everyday life, from food preparation to personal hygiene and cleaning the house. As a consequence, they often merge their life rhythm with the patient – without distinction between personal life and work,” says Antonino.

Furthermore, this right to a free day isn’t always honoured by the “family-employers”. It means these women rarely have any activities outside work – they are stuck in the home in which they work. And the emotional trauma of being away from their families is another issue.

Despite some emerging health problems, Claudia has still delayed her dream return - to Bulgaria, her family and the house in the countryside she built several years ago with part of the money she earned in Italy.

And after so many years with the families of others, it's safe to say Claudia deserves to enjoy the life she's worked so hard for back home - with her own family.