Avignon: Reality, refugees and theatre

Published on

Translation by:

Gabriel UmanoDriven by a generation of committed actors, this year's Off festival in Avignon presented an unprecedented number of works devoted to migration. What can theatre achieve when the political scene across the continent is in turmoil? It's a vast question we took with us to one of the 133 theatres the largest live performance festival in the world brought to life earlier this summer.

It's 7 pm when we reach the rue des écoles and, despite the heat in Avignon, the actors are still ploughing through their performances. After politely refusing to take the umpteenth flyer we're handed, we enter the Manufacture garden, the "in of the Off" as some like jokingly like to call it. This specific theatre specialises in contemporary, socially-aware pieces and is very popular among the festival-goers. Tonight again, the garden is full of spectators. Everyone has come to watch No Border written by Nadège Prugnard, who spent two years in the Calais Jungle. But we have a meeting with Pascal Keizer, the president of Manufacture, who has decided to present a series of special pieces for this year's edition of the festival.

Walking the plank of empathy

This year again, Manufacture's programme is perfectly in line with the news. While the "In" festival by Olivier Py explores "gender, trans-identity and transsexuality", the Manufacture collective has chosen to form a partnership with the Arab Arts Focus (AAF) – an organisation in charge of promoting international shows from the Arab world – for the "Off" festival. On Manufacture's stages, the Manufacture-Patinoire and Château de Saint-Chamand, there are a total of seven shows (including five presented by the AAF) that focus on the Arab world and/or migration.

Was it the collective's intention to focus on this particular issue, though? Perhaps. But with a genuine smile, the president Pascal Keiser who looks a bit like Adrien Brody, prefers to put the spotlight on the work of the artists: "Our programme is a mirror-image of the artist's proposals this year. Many artists, writers, directors, photographers chose to focus on this theme which, we have to admit, has been pushed aside by the media for a year." He refers to the "Calais Jungle" and its dismantlement at the end of 2016, an event newspapers covered much less than the confusing "refugee crisis". He cites the screening of the film by Boris Kommendijk No Border, Guy Alloucherie, as well as the exhibition Ville de Calais by Henk Wildschut at the school of art, the fourth location chosen by Manufacture in the framework of the festival.

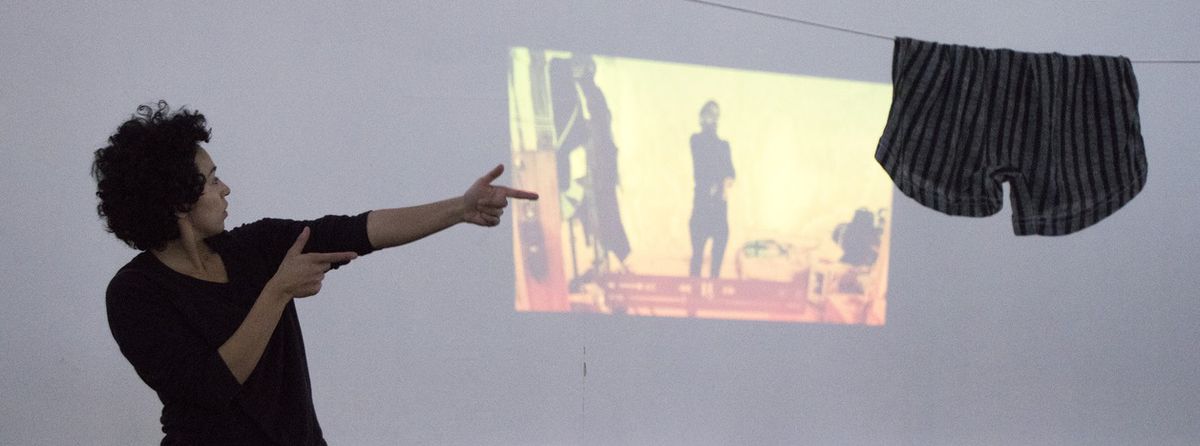

Readings, exhibitions, projections, shows and performances are all part of Manufacture's programme for the 72nd edition of the Avignon Festival. It's a diverse body of artworks that try to address all aspects of the so-called "refugee crisis", but also try to push their viewers out of their comfort zones. This is precisely what Palestinian choreographer and associate artist from Dance Base in Edinburgh, Farah Saleh, aims to do with her show Gesturing Refugees, presented in Saint-Chamand. With her piece, the artist questions, interrogates and destabilises her viewers.

"Theatre is a call to spectators at a given place. It's a very physical form of representation, which makes it different from many forms of media or other content. All the tensions, misfortunes, inequalities of the world are translated with much more force. Sometimes it's hard for some reductive minds to understand that we are facing characters and not facing what people think on stage, and that upholds a theatrical tension that is very strong."

To get there, we go to Manufacture before boarding the free shuttle bus. Once off the bus, we cross a small pine forest with the sound of cicadas in the background and finally arrive at the building, which also hosts a neighbourhood library. Farah Saleh meets us in the hall. At first, it's difficult to hear her slender voice, but a silence fills the room shortly thereafter. The choreographer explains to us in English that, before entering the room, her aim is to prepare us for our future status as refugees. Fleeing one's country doesn't only happen to others... better be prepared. With a firm smile on her face, Farah asks us to hand over our IDs: "It's important that you have nothing on you indicating your country of origin because, in case of arrest, the authorities won't know where to send you back to." Everyone is handed a small plastic bag in which to put their mobile phones, in case the boat capsizes. She also teaches us to whistle using two fingers under our tongues in case we need to alert the rescue team. Then, we're given one last glass of water – "it's drinkable, I've checked" – and we're off.

"Many people don't get it"

In the room, the chairs are placed on stage. We fill out an absurd questionnaire (brand of the shampoo we use, colour of our first bedsheets...) that serves to divide us into two groups. Two projectors simultaneously broadcast three testimonies of refugee dancers and choreographers, probably recorded during Skype interviews. The artists grab the public's attention by making them listen to their stories and traumas, and watch their body movements. These three men also address prominent questions they had in mind throughout their journeys: do I really have to hand over my papers? What memories will I hang on to in difficult moments? Will I forget what it is to love, what it is to laugh? On this hot summer day, we are no longer just reading their testimonies in the papers, we are living them.

However, at the end of the show, the word that stays in our minds the most is not "empathy" but "perplexity". Many people don't understand what they have come to see and are disappointed that they didn't get to sit comfortably in armchairs. Instead, they were seated on chairs on the stage and forced to participate. We take advantage of our trip back to speak to members of the audience. Under the shade of the pines, a group of sixty-year-olds rush back to the shuttle. One of them gives us a piece of their mind and even some suggestions: "If they would have put us in a boat it would have been different, but there...". Another group member expresses what embarrassed her the most: "She speaks English, many people didn't get it." In the bus, a woman hiding behind big black sunglasses notices our microphone and gets carried away: "I guess at first, the idea is that people are sorted out based on random criteria, that the gesture is related to past traumas but hey, I call it a lazy show." Her four friends agree. We ask one of them what the purpose of theatre is, then? She hesitates and responds, quite sure of herself: "It's an artistic gesture that allows you to transmit an emotion to an audience, to touch them with this emotion, so that they appropriate it." She pauses for a second before continuing, lowering her voice: "Maybe we're frustrated as they have been frustrated." Frustrated, angry, lost in the face of an unknown language that you don't master... Indeed, it seems that in a heartbeat, Farah Saleh succeeded in making us all apprentice refugees.

Writing out reality

But is this really the role of theatre? According to Pascal Keizer, theatre is a "cure for media amnesia". Certainly, but does it necessarily have to be expressed through tears? While the media informs, theatre moves? The Manufacture's president prefers giving his own definition: "Theatre is a call to spectators at a given place. It's a very physical form of representation, which makes it different from many forms of media or other content. All the tensions, misfortunes, inequalities of the world are translated with much more force. Sometimes it's hard for some reductive minds to understand that we are facing characters and not facing what people think on stage, and that upholds a theatrical tension that is very strong."

The man knows what he's talking about. He was at the heart of the controversy last year by programming the show Moi, la mort, je l'aime comme vous aimez la vie (meaning "I love death the way you love life", e.d.), a play adapted from a text by Mohamed Kacimi dedicated to the final hours of Mohamed Merah, which was poorly received by some families of victims. The Israeli culture minister even asked his French counterpart to ban the play. A terrorist as the protagonist of a theatre piece? Out of the question. At the time, the president of Manufacture didn't even flinch. The controversy remained at the foot of the ramparts. For almost 20 years now, Manufacture has been defending the notion of contemporary, innovative and committed theatre and, since Avignon, has become a breeding ground for "writing out reality". Gesturing Refugees is one of the most telling examples this year.

It's 7:30 pm and the reading will soon begin. We say goodbye to Pascal Keizer, who is on the phone, and cross the garden to enter the hall. As we walk by the bar inside, we imagine a sign saying "go cry elsewhere". A remedy for media amnesia, a support for reflections and debates... here, theatre speaks, it doesn't contemplate.

Cover photo © Ana Rodriguez

Translated from Réfugiés au théâtre : Avignon sur le pont