Avignon Festival 2016: Theatre is dead - long live theatre!

Published on

Translation by:

Phil W. BaylesWith more and more elaborate set designs, screens and cameras on stage, and live music in the wings, theatre is evolving – but does it run the risk of losing something in the process? Two shows from this year’s Avignon Festival stand out: Ivo van Hove’s The Damned, and All Against All, directed by Alain Timár.

Everything is in place. The screen, the two Steadicams, the audience, the props, and of course the actors of the Comédie Française. If some spectators are surprised by the two cameraman on the stage, many will be unphased: the fusion of live theatre and film is in vogue these days.

Thomas Ostermeier used screens for his production of Hamlet, performed on this very stage at the Palais des Papes in 2008 before moving to the Schaubühne in Berlin. The Volksbühne theatre (also in Berlin) used Steadicams for its recent production of Castorf’s Die Kabale der Scheinheiligen. Das Leben des Herrn de Molière. Audiences in the United Kingdom are used to seeing plays from the National Theatre broadcast live to cinemas across the country.

Thomas Ostermeier used screens for his production of Hamlet, performed on this very stage at the Palais des Papes in 2008 before moving to the Schaubühne in Berlin. The Volksbühne theatre (also in Berlin) used Steadicams for its recent production of Castorf’s Die Kabale der Scheinheiligen. Das Leben des Herrn de Molière. Audiences in the United Kingdom are used to seeing plays from the National Theatre broadcast live to cinemas across the country.

As the sun sets over Avignon, the cameras are turned on and all eyes swivel towards the screen as the play begins. It’s practical, obviously, for those sat in the cheap seats who wanted to see the stage a little more clearly. But others will be annoyed – after all, they came to the theatre to get away from screens! Still, Ivo van Hove’s use of cameras is nothing compared to Castorf. In the latter’s most recent play, the audience spent four hours of a five-hour play staring at screen while the actors remained hidden by the scenery. Van Hove uses the screen as a tool, to shrink or expand the scene. As two characters meet in the middle of the stage, the screen shows us images of other actors changing costumes further off. Similarly, we get a tour of the interior of the Palais des Papes when one cameraman dashes off between the cold stone columns in pursuit of Elsa Lepoivre. It’s technically impressive, but not much more.

The actress confirms, somewhat surprised herself, that the troupe spent “just three weeks in Paris and then a week here, so the whole show came together in a month.” Van Hove, for his part, spent more than a year making technical decisions and designing the set. Guillaume Gallienne – a César winner who’s spent 11 years as a member of the Comédie-Française – loves to tell interviewers about long discussions with the director, only seldom talking about the psychology of the characters.

“The stage directions, the relationship between the video and the music, everything is meticulously planned in advance like it would be in an opera,” he says. “Our characters are never really discussed in terms of motivation or psychology: Ivo tells us to follow the music instead…” Right.

As a result, the critics praised the professionalism of the actors (since yes, rehearsing a play in three weeks is an impressive feat), and the richness of the play (its special effects, the live music, the faultless camera work) and… not much else. Even the most excited reviewers couldn’t help but note the moderate reactions of audiences that were slow to start applauding. The Damned is great theatre, yes, but it’s also bland. The noted theatre critic Jacques Nerson summed it up perfectly in his summary of the festival: “I was never moved by the show, I was always detached from it.” We admire, we fawn, but we’re never affected. Shocked, maybe, but not affected, since van Hove “is often trapped by fascinating but facile ideas.”

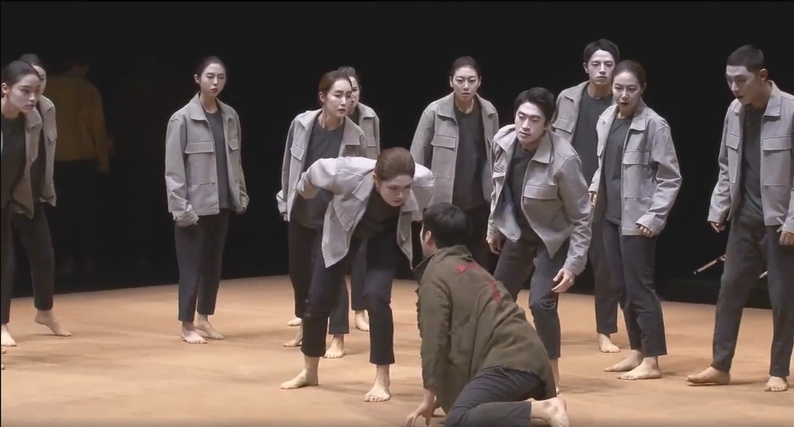

Surprisingly there’s no screen, no unexpected nudity and no terrible taboos to transgress in All Against All, a play written by Arthur Adamov in 1952 and directed by Alain Timár. Here it’s the power of the troupe, not the special effects, which the audience really notices. There are 15 of them (nine men, six women), swapping roles, singing, proclaiming the decisions of a government that could soon become our own – or maybe it has already? These are the real special effects: the magic of the troupe, the movements and chants timed to the millisecond, the strength and power they give to their lines flowing from their bodies to ours. There are 15 of them but they act as a single voice – one script, one play. As Timár says: “In what I call ‘poetic and symbolic realism’, the voices and gestures of the actors, the music and even the set design are all part of the same script.”

A return to the 'essence' of theatre

The costumes are left on in a line on the floor. Just like The Damned, nobody leaves the stage, and actors change costumes in full view of the audience. But the tables piled with glittering props in the Palais des Papes have been replaced by a stark austerity. There are three colours for three different castes of characters. Two styles: a simple knitted number as a mark of poverty, another more stylish outfit for the wealthy. Coats with a red sign for refugees, and overalls for the working people. Actors help each other change costumes in a matter of seconds in the semi-darkness as the live drumming of the excellent Young Suk echoes around the room. Nothing is said, but everything is clear.

When the last notes have sounded the troupe is revealed, standing at the edges of a white square. In one voice they announce the setting, the names of the characters and who will enter the stage. When their names are called, they take a step forward. In the background they remain neutral; they’re still actors, not quite themselves and not quite someone else. They’re just the supports, voices that are silenced for a moment. In the moments before they reply, their bodies contort and they become characters: Jean slumps down, depressed; Marie hangs her head in shame; the Mother limps with her back bent. One by one they step into the white square, where suddenly we see furniture in a room or walls on a street – we see where we are, without anyone having told us.

So much from nothing at all

Of course, certain words resonate – “refugees”, “camps”, “executions” – but nobody has started shooting, at least not yet. In comparison, The Damned sorely lacks finesse: it really wasn’t necessary to end that play with a cast member firing wildly into the crowd just in case anyone hadn’t yet understood the parallel between Nazism and modern day massacres. Timár has far more faith not only in his audience but also in the text and the players. The ‘camps’ they talk about are not the last remaining vestige of a war from another century. They exist right now, and we close our eyes to them while they’re built, these camps full of people who we don’t want to welcome and would rather keep out of sight and out of mind.

Jean and Zenno play executioners then victims then executioners again, bringing death and also fearing it. They aren’t strangers from foreign lands: their faces are white. Their absurd situation is also ours. We shut our eyes and our borders to these refugees whose lives are threatened, we shut them in camps, monitoring their comings and goings as if we too are threatened. Regardless of our gender, our religion or our wealth we are all potential victims. Suddenly we are alone, all against all, and any kind of unity seems very far away.

The play is long, but it doesn’t feel long because even though the script is as simple as that of The Damned, it takes time to digest what is going on onstage. A script like this doesn’t need any frills or flourishes. When it is respected, art like this comes within a hair’s breadth of genius. In the original film of The Damned, Luchino Visconti magnified the images to create something sublime. Timár, meanwhile, returns to the primal state of theatre, searching for that Greek catharsis in which the audience can scream out their deepest fears. As for van Hove, he flits between the two and in the process creates a painting. It’s a magnificent tableau, painted with the finest oils and brushes, but it doesn’t belong on a stage – it belongs on a wall in a gallery.

At the end of All Against All, tears welled up in every eye. The audience leapt to its feet, and cries of “Bravo!” rang out over the applause. They were blown away by the power of play, of the actors and the set designers who managed to make so much out of nothing at all – as opposed to van Hove, who made nothing out of so much.

Translated from Avignon 2016 : le théâtre est mort, vive le théâtre !