At the Crossroads of History: Transylvania

Published on

Spread on the southern range of the Carpathian Mountains in Romania, around 200 villages and their patterns of settlement, built by German Saxon settlers and dating back from the 12th century, mark one of the last untouched Medieval landscapes in Europe, through their planning, agricultural practices and social traditions.

Seven of these villages with fortified churches are recognized as UNESCO’s Global Heritage Sites for their “specific land-use system, settlement patter and organization of family farmstead that have been preserved since the late Middle Ages.”

Despite the villages’ recognized international cultural value, post-communist aspirations for modernization and the large-scale migration of ethnic Saxons to Germany brought under threat this invaluable European cultural mosaic, combining elements of Romanian, Saxon and Gypsy Heritage. At the same time, many young Romanians, keen on embracing the commodity of Western European life, are choosing to build new houses with modern conveniences rather than renovating historical family ones, which are left to degrade or are simply demolished. Even when restoring these century-old houses, many people use cheap, poor quality modern materials, whose design is not in accordance with the architecture of these traditional houses, partly because those produced using traditional methods are scarce and expensive. This ultimately decreases the historical relevance of these places.

The Romanian government has struggled to preserve these cultural treasures from destruction, as it provides meager financial and regulatory support and the majority of funding supports agricultural activity. Global Heritage Fund (GHF), an international nonprofit, has taken interest in saving these village communities through documentation, awareness raising and outreach, as well as the revival of traditional and sustainable building crafts, by partnering with Associata Monumentum and the Anglo-Romanian Trust for Traditional Architecture (ARTTA), two private charities dedicated to protecting and maintaining Romania’s built heritage, alongside national and local authorities.

In order to assist with the urgent repairs needed to preserve thousands of historical houses, GHF has created an emergency repair fund, providing immediate mending and restoration of their structure, roofs or facades, which would otherwise be lost. GHF’s outreach lays out a plan to provide the tools and training to preserve the architecture using traditional construction methods and materials, such as hand-made bricks and terracotta tiles as well as wood brought from surrounding forests. As wood-burning and local tile kilns have been challenged by the presence of major manufacturers, GHF, alongside ARTTA, have raised funds through a 2013 crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo to construct a traditional kiln in the village of Apos. The kiln was completed in 2014 and will start production in the spring of 2015. Apart from ensuring the materials for authentic restoration, the kiln will also provide jobs to local communities and ensures that the knowledge of the handmade traditional methods of making bricks and tiles is preserved and passed on to new generations.

At the same time, GHF is also undertaking photographic documentation of these villages, in order to create an archive of current and historical photographs of the architecture and landscape of the region, while also supporting the implementation of local heritage policy, ensuring the protection of traditional structure by working with local and national authorities. One of the more recent efforts to document the remarkable beauty of these Carpathian villages was to commission award-winning illustrator, George Butler, to capture their communities and rural lifestyles. The illustrator spent two seasons living with the locals, in order to capture the “endangered, historic livelihood that often escape the media eye.” His work was displayed at the Romanian Cultural Institute in London between October-November 2014. The exhibited art work was available for sale and sold out in the first week with the proceeds going to support GHF’s work in Transylvania.

In order to continue raising awareness about these sites and funds for their restoration, GHF, in partnership with Original Travel, a responsible travel organization, is inviting all individuals on a special cycling tour across the Transylvanian landscape. The tour is taking place between June 2-6, 2015 during which time cyclists will cross ten villages as well as their surrounding hills, meadows and forests, raising money for every kilometer covered. Participants also have the opportunity to enjoy Romanian cuisine, and experience local arts such as Transylvanian art and traditional Romanian dance performances.

The funds raised from all participants will be used to support the Carpathian Villages Preservation Project and aims to achieve three main goals this year. The first is to expand documentation of some of Romania’s most significant rural heritage sites that will serve as a guide and reference point for regional officials, architects and villagers. The second objective focuses on public outreach via education and advocacy programs that will help to promote heritage protection, and finally to support the repair and restoration work on the traditional Transylvanian houses most in need.

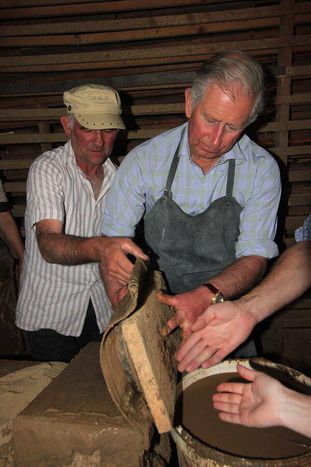

Some of the community development initiatives are already underway. In the summer of 2014, 60 house facades started being consolidated and restored, which pertained both to individual owners as well as the local council. In addition, preservation guidelines were drawn up to assist the local communities in understanding the importance of the architecture, the use of authentic materials over modern construction, and offering workshops to over 1,000 homeowners, a project supported by HRH Prince of Wales who opened his home as a model site in the village of Viscri.

There is a growing thirst for knowledge and dialogue among the local communities. Whereas in the past, villagers were often walled out of large-scale archaeology projects, GHF’s methodology places them in prime positioning for the long-term success and sustainability of a site. They are, after all, the site’s true stakeholders. This sense of identity and responsibility is a catalyst for development and economic growth, as equally so as having the site protected and well managed to benefit from incoming tourism.

The key is to diversify the local economy so it does not rely on one source of income, such as agricultural activity based on one or two crops, but to allow new opportunities for more people with a different set of skills and capabilities. At the world’s oldest known temple site in Turkey, local communities are practicing this approach, with the support of the GHF.

Gobekli Tepe is an ancient site rising from the dust, and developments here are not just changing the way archaeologists view religion and society, but also how heritage impacts the local community and stimulates in-country investment by private bodies and the government. Gobekli Tepe is one of GHF’s most successful projects worldwide.

These changes are best presented through the personal accounts of two workers – Tarik and Hikmet – both from neighboring Orencik Village, each in different periods of their lives. The son of a farmland owner, Tarik joined his brothers as a worker at Gobekli Tepe after the earth that sustained him and his family for many years revealed a Neolithic site under an excavation mission led by the late Dr. Klaus Schmidt. The land was expropriated by the Turkish government in the 1990s. Since then, Tarik’s father and three brothers have worked at the site as guards or workers and have earned their livelihood from the site’s preservation undertaking.

Tarik’s involvement in the project inspired him to pursue an academic education in business and tourism. The 25-year old is the first and only villager from Orencik to ever attend university. During his studies, Tarik has worked as a guide, accompanying foreign tourists around Gobekli Tepe, in English. These skills were not acquired in the classroom, nor were they acquired in evening classes led by international language schools, but from his interaction with people over the years. In late 2014, Gobekli Tepe received a visitors’ center, one that now employs Tarik for his experience and thorough understanding of the region’s cultural heritage.

Hikmet has worked at the excavation site alongside Dr. Schmidt from the very start, 18 years and counting. While the excavation seasons last only four months, during the spring and autumn, Hikmet has engaged in numerous construction projects over the years. Now in his 50s, Hikmet is an expert in the field, including archaeology and conservation practices. He has shared his knowledge and conducted held training workshops for many young villagers in earth structures and mortar up until March 2014. Hikmet has since been elected mayor of Orencik, his home village. Owing to his extensive experience and knowledge on Gobekli Tepe, he is working to improve the physical, socio-economical and tourism infrastructures in the village. Having seen first-hand the impact of community-driven development projects, Hikmet has set another goal, to be one of the stakeholders in similar initiatives, helping to build capacity in Orencik and generate higher income for its inhabitants, officially placing the village on the map.

The goal in Transylvania is very similar. All of the preservation work is implemented by experienced workers who are handing over the historic trade of traditional tile and brick production to the younger generations, many of whom are unemployed and without access to vocational opportunities. Although widely overlooked across the EU, the untapped socio-economic potential in this part of Romania is actually a driving force for GHF’s team and on-site partners. Seeing the case for Turkey, it’s hard to argue with the facts and the possibilities that projects of this nature offer to relatively impoverished communities. The Carpathian Villages Preservation Project is working to generate such opportunities by leveraging traditional trades and existing infrastructure with creative strategies to help diversify the local economy and generate jobs, relying on more than the region’s rich agriculture production.

In this way, local communities are motivated to claim responsibility and ownership for their built heritage. Cultural language in this sense is not just a verbal outlet, so to speak, but also one that derives its meaning from a shared history and monumental expression that has been passed on for generations by its master architects, the people.