At Home with Comrade Stalin

Published on

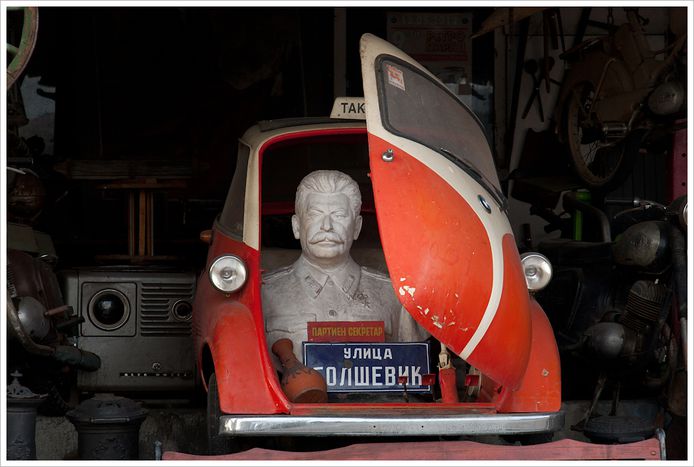

A cult of remembrance on two floors. In a museum in Joseph Stalin's hometown of Gori, the native Georgian is still celebrated.

My tour guide promotes the Stalin Museum as the most bizzare and exciting museum in Georgia. The museum was built four years after his death in 1957. At the bus terminal of the Georgian captial Tbilisi, the taxi drivers offer to drive me to Gori, without even asking about my destination — apparently I'm not the only tourist whom the supposed Stalin cult brings to his native town.

In the unspectacular, hot and dominated with one-storied buildings, each one resembling the other, the museum and its park are the centre of the city. Entering, I'm already greeted by a portrait of the dictator, as a group of Chinese tourists pose and smile for a photograph with Comrade Stalin.

The tour through the museum takes about two hours and shows Stalin as a young communist, a technological revolutionary and victor over Hitler, but I also see his private furniture, gifts from the state and him, and his railway car that's equipped with a bathtub and air conditioning. It's as though the aim of the exhibition is to impress the visitors with Stalin's extravagant estate, while on the side a few of his 'achievements', like the first Soviet tractor, are showcased. Nobody talks about the Great Purge that also took place in Gori.

However, my tour guide reads that the museum as been renovated and shows me Lenin's political testament, in which he warns of Stalin's thirst for power. Because the descriptions are mainly in Georgian or Russian, I don't know whether the museum has any interest to impart such information or whether it's simply not there.

After the tour, you can buy souvenirs, like a Stalin tea service or t-shirts in the gift shop. Instead, I ask the museum guide about why the museum isn't more critical. Objectivity, he says, is the reason why good as well as bad aspects of Stalin's reign must be presented. I wonder about the bad reasons. He asks me, astonished, if I hadn't seen the repression show room.

After the tour, you can buy souvenirs, like a Stalin tea service or t-shirts in the gift shop. Instead, I ask the museum guide about why the museum isn't more critical. Objectivity, he says, is the reason why good as well as bad aspects of Stalin's reign must be presented. I wonder about the bad reasons. He asks me, astonished, if I hadn't seen the repression show room.

While I'm lead there I realise why the room, with its unlabelled door which looks like a janitorial closet in the imposing house, didn't catch my eye. Behind that door is a small room with a suit and a dress are mounted on the wall. "The owners of these clothes died in the Gulag," the guide tells me. "That's it?" "That's it." And I'm back in the park, in front of the museum, where Stalin's birth house stands under a pompous canopy.

The constant refusal of the citizens of Gori to deny the darker side of Stalin's past could by explained by the Stalin-tourism that supports the city. But not only in Gori, but in all of Georgia, the attitude towards the most famous modern Georgian is not especially critical. Between 1921 and 1941, 72,000 Georgians were shot and 200,000 more were deported. Yet the Stalin cult doesn't suit Georgia at all, where almost everyone labels themselves as anti-Soviet.

Most Georgians don't differentiate between the Russian Federation and the Russian-led Soviet Union. The most recent conflict with their big neighbour was the conflict in 2008, where Georgia lost the territory of South Ossetia, which has declared independence. The wish for complete emancipation from Moscow and national pride mark the political thinking in Georgia; Soviet nostalgia is rare.

It seems as though Stalin isn't worshipped as a politician of the USSR, but as a Georgian. This simple reason is enough to create and maintain a cult around his persona, perhaps because the Stalin era was never completely shrugged off in Georgia. In the 1990s, the country struggled with fundamental problems and there was no time to think about the past. Today, the economic situation has improved for most Georgians. This new-found prosperity also affects how history is viewed, a Georgian acquaintance tells me. Most of the Georgians under 30 find the museum in Gori as peculiar as I. "Everything in Georgia changes," she says. "Even the museum won't always be here like this."

Translated from Gori: Zuhause bei Genosse Stalin