Armenia: In the country of stones

Published on

Translation by:

Emily SpencerIn his book In the Country of Stones, published mid-June, the French photographer Nicolas Blandin tells us about his journey across Armenia. The story unfolds through the people he met and the landscapes of an "isolated" country.

cafébabel: Why do you call Armenia the country of stones?

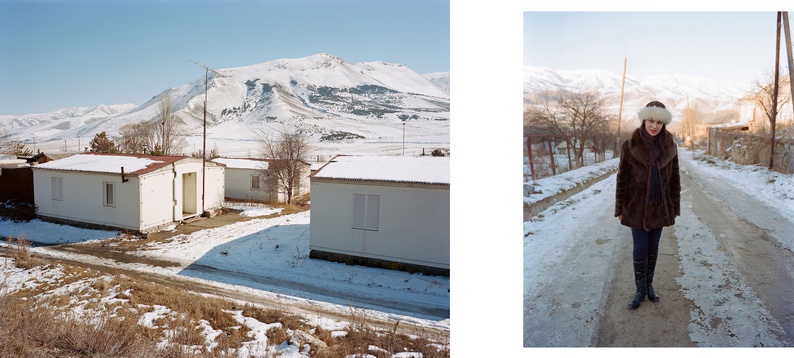

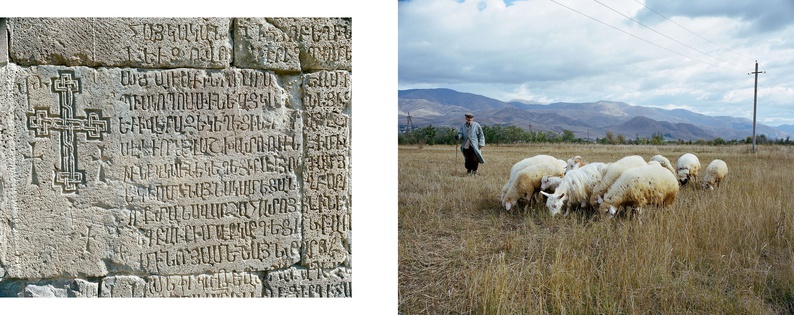

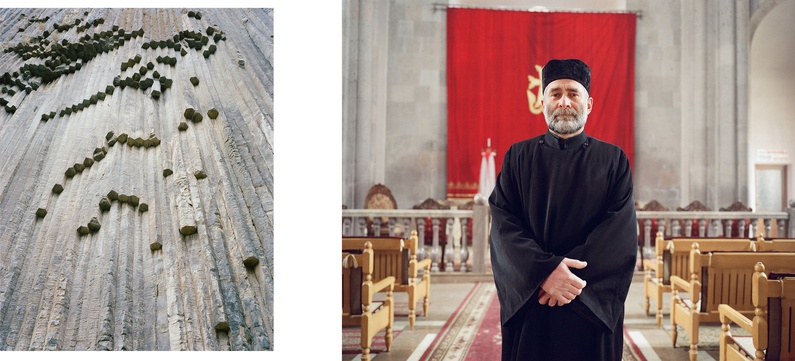

Nicolas Blandin: Armenia (called Hayastan in Armenian) is often nicknamed Karastan [NB. literally 'country of stones'] by its inhabitants, due to the vast mountainous regions and eruptive rocks that dominate the landscape. According to an Armenian legend, when God created the world, he poured soil and rocks through an enormous sieve. The soft soil landed on one side while the stones fell on the other, which is where Armenia can be found today.

cafébabel: Which version of Armenia did you want to present in your project?

cafébabel: Which version of Armenia did you want to present in your project?

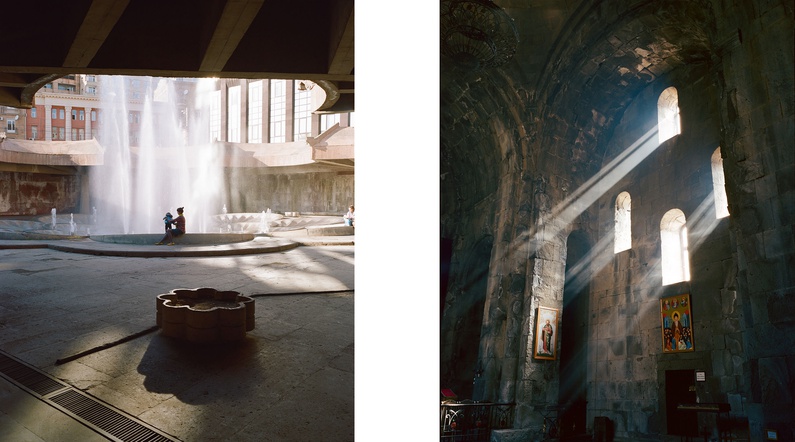

Nicolas Blandin: My pictures are, above all, the result of a very personal and subjective experience. I found several aspects of Armenia fascinating; the way that the history and collective memory manifest themselves visually in the landscape, whether it is through the imposing remnants of the 71 years of Soviet rule, the repercussions of the 1988 earthquake or even the issue of the Armenian genocide. I was also moved by the personal stories of the people that I met, and the symbols that showed the fact that Armenia was the first country to adopt Christianity as its main religion (in 301 AD). And finally there is the elusive nature of this isolated country - both geographically and politically - which seems to change according to its own rule, with undeniable moments of grace and beauty in spite of the economic difficulties and the ruggedness of the countryside.

cafébabel: What sort of trip did you make to Armenia ?

cafébabel: What sort of trip did you make to Armenia ?

Nicolas Blandin: I hitchhiked through Armenia with my girlfriend for three weeks in September 2013. We had heard about the legendary Armenian hospitality, but we hadn't expected the warmth, curiosity and benevolence that awaited us. Some villages receive so few visitors that, when foreigners do pass through, they are readily greeted and invited for a coffee. During the trip we had the feeling that, at times, we were reconnecting with long-lost cousins who we had decided to visit. I seized the opportunity to undertake some voluntary work at the Spitak YMCA in order to spend more time in the northern part of the country during the winter months.

cafébabel: What would you recommend to a young, European traveler?

cafébabel: What would you recommend to a young, European traveler?

Nicolas Blandin: Armenia is a country with a rich history, culture and contrasts. It is worth making a trip to, if only for its curious and open-minded citizens. The Southern Caucasus is a fascinating region. Visitors are placed at the crossroads between Europe, Russia, Central Asia and the Middle East.

cafébabel: Is it easy to travel through Armenia?

cafébabel: Is it easy to travel through Armenia?

Nicolas Blandin: With Russian and Armenian being the main languages, English is scarce. Even in Erevan, the capital city. Therefore, some resourcefulness is required in order to overcome the language barrier and the difficulties vis-à-vis the lack of infrastructure and information. However, the curiosity and benevolence of the Armenian people compensate for any inconveniences.

cafébabel: What sort of people did you meet in Armenia?

cafébabel: What sort of people did you meet in Armenia?

Nicolas Blandin: The fact that I was constantly on the move, taking photographs in all sorts of places, indulging my curious mind, allowed me to meet all sorts of people. I met young people, old people, locals, members of the Armenian diaspora in search of their roots, people whose family members are scattered all over the world, families who find themselves separated for several months each year while men work in Russia to make a living...

cafébabel: What was the strangest moment of your trip?

cafébabel: What was the strangest moment of your trip?

Nicolas Blandin: When we were hitchhiking near Khor Virap, we had a funny experience. A car stopped and we introduced ourselves in the normal fashion, but when my girlfriend said that she was German, the driver Samuel (who we later learned had lived for a year in Germany during the time of the GDR) said jokingly in German: "Was ist los ? Nichts ist los. Arbeitslos !" [NB. "What's up? Nothing! No job!"]

cafébabel: In Europe, Armenia is sadly still an unknown country. If you type Armenia into Google, the third entry that comes up is "the Armenian genocide." What, according to you, are the three best aspects of your country?

cafébabel: In Europe, Armenia is sadly still an unknown country. If you type Armenia into Google, the third entry that comes up is "the Armenian genocide." What, according to you, are the three best aspects of your country?

Nicolas Blandin: One of the many monasteries (some date back to the 4th century) perched on a hilltop, above a lake or a canyon, such as Khor Virap and its impressive view over the Ararat, Noravank and its red mountain ranges, Tatev or even Sevanavank, the Sevan lake, to name but a few.

The paintings of Minas Avetisian. His former residence in Jajur, close to Gyumri has been converted into a mini museum. And who can forget the green walnut preserves? Fruits, vegetables, lavash (a soft, thin unleavened flatbread) and the Armenian gastromony, in general, is worth the trip.

The paintings of Minas Avetisian. His former residence in Jajur, close to Gyumri has been converted into a mini museum. And who can forget the green walnut preserves? Fruits, vegetables, lavash (a soft, thin unleavened flatbread) and the Armenian gastromony, in general, is worth the trip.

cafébabel: The world is still very divided on the issue of the genocide. Did you manage to talk to Armenias about their painful past?

cafébabel: The world is still very divided on the issue of the genocide. Did you manage to talk to Armenias about their painful past?

Nicolas Blandin: It is clear to me that the Armenian people want the memory of the victims to be honoured and for the genocide to be officially recognised. But official recognition of the genocide is hampered by significant diplomatic, financial and territorial conflicts.

cafébabel: It's been 25 years since the fall of the Soviet Union. Do young Armenians remember this era?

cafébabel: It's been 25 years since the fall of the Soviet Union. Do young Armenians remember this era?

Nicolas Blandin: It depends on which young people you ask and how old they were at the time. For some, especially in the northern part of the country, the fall of the Soviet Union coincided with the fallout of the 1988 earthquake. Two shocking events that are hard to forget.

cafébabel: It is often claimed that former Soviet states are still 'divided'. How do young Armenias feel about their relationship with Europe and with Russia?

cafébabel: It is often claimed that former Soviet states are still 'divided'. How do young Armenias feel about their relationship with Europe and with Russia?

Nicolas Blandin: Since it became independent in 1991, Armenia has maintained a close relationiship with Russia, for economic and political reasons. The country is, effectively, geographically landlocked and above all politically blockaded by Turkey in the west and Azerbaidjan in the east. Faced with a lack of job prospects, many Armenians, young and old, are choosing to travel to Russia to work for at least part of the year.

That being said, young people are also looking west to Europe and the United States, which are home to a large Armenian diaspora. Armenia's foreign policy seems to be searching for more and more support from the West.

That being said, young people are also looking west to Europe and the United States, which are home to a large Armenian diaspora. Armenia's foreign policy seems to be searching for more and more support from the West.

__

__

To read : Nicolas Blandin - 'In the Country of Stones' (Juin 2017, Another Place Press)

Translated from Arménie : Au pays des pierres