Armand Gatti: reading poetry up trees

Published on

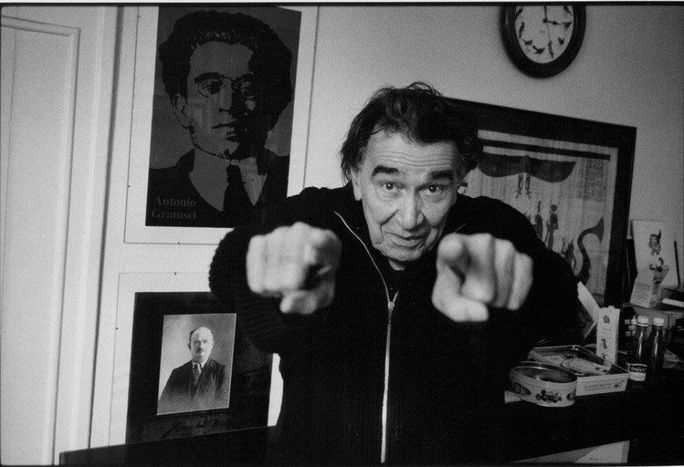

There are a thousand things to say about Armand Gatti, and a thousand questions to put to him - his output is vast and his enthusiasm great. Born in Monaco, the son of immigrant Italian parents, he joined the French resistance in the second world war. During this time, he was sentenced to death but pardoned, and was taken prisoner in Germany but escaped

He has since taken on the mantle of journalist, anarchist, scriptwriter and social activist.

A complex and controversial man, who is nevertheless admired, Gatti propagates his own myth. Like his namesake the cat, (‘gatti’ being the plural of ‘cat’ in Italian), he seems to have led many lives. There is however, one title which has remained constant throughout: that of poet.

On 12 April in Montpellier, the association Ideokilogramme welcomed Gatti for the final stage of a project which began in 2010: the exciting journey that has been 'La Traversee des languages' (The crossing of languages).

The medieval arches of the Salle Pétrarque have a softness and solemnity which seem befitting for the presence of a man such as Gatti. Seated alone at a table, encircled by some of those involved in the Montpellier project, whose admiration is palpable, Armand Gatti speaks. His words are as much History with a capital ‘H’ as his own story, with two becoming one and the same.

Time loses all sense of meaning as Gatti speaks, and one feels that for him, everything in life is intimately connected: the loss at the age of 18 of the woman he loved - a young Jewish girl sent to a concentration camp; that all important meeting with Mao Zedong in China; his theatrical exploits with his ‘Loulous’ (unemployed people, substance abusers and delinquents, with whom Gatti worked during his earliest experiences in the theatre).

‘One day, I realised what I wanted to say about the revolution: poetry’

One day Armand Gatti made the decision to abandon his career as a journalist to become a poet. He wanted to use the language of poetry to render all things tangible and make them accessible to everyone. The months spent in the underground forces during the war, in which he read Michaux, Gramsci and Mallarme up trees to keep himself from falling sleep whilst on watch, together with the meeting with Mao Zedong (‘Language holds the only truth!’) convinced him that the revolution and the struggle should remain a constant fixture in his life, and that he should continue it with words.

Gatti thus began to write, and decided to bring his texts to the stage. An anarchist attracted by communist ideas, he understood very quickly that in order to reach the public he wanted to address (the working classes and those on the margins of society) he would have to take an active role in the show himself. And so, he made his debut with his famous experimental theatre pieces - notably with the Loulous: amateur actors, who participated in projects lasting sometimes only two, sometimes ten months. Over time, both the show and Gatti’s scripts became more elaborate, feeding in turn the lines written and songs brought by the other players, who were all fully immersed in this experiment.

According to Matthieu Aubert, Gatti has that rare quality of ‘working with people as individuals’. Gatti and his young assistant first met in 2003, leading to their collaboration in numerous projects (in the framework of supported by Gatti’s organisation ‘la maison de l’arbre’ (‘the tree house’), most recently co-directing the project Traversee des languages in Montpellier.

The act of staging a showcase of around fifteen of Gatti’s works around a central theme of mathematics is, on first consideration, a daunting task. However, what remains today of this endeavour has, conversely, a rather playful feel: a blog consisting of participants’ stories collected during writing workshops; the motivation, three years later, for former participants to bring the project temporarily back to life and to welcome Gatti back into it; a book published by l’Entretemps, which retraces the three months of its creation. Finally, there is the letter read by Haciba Boucenna, written by the young Charifa Ahmiti, which declares that this drama, with its poetry, has had a lasting effect upon her.

In the Salle Petrarque, Armand Gatti reads a text by Francis Bailly, interspersed with songs and readings by the other participants. The subject matter is dense, and sometimes difficult to understand, but although you may find yourself lost, by the end, you have perhaps recaptured a sense of humanity.

The reading over, I manage to catch the attention of this venerable elderly gentleman (Gatti will be 90 next January). I manage two or three rapidly asked questions – about the roots which are so important to him, the loss of which he feels so greatly that he wants to render them alive again through his words; about poetry as the only solution; about Mao as the only model (‘after that, I saw tremendous things’). Finally, about trees, firmly rooted in the ground, but always with their eyes on the skies, like the home port of a poetry which is always looking to far off lands: the poetry of Armand Gatti, with which he invites us to follow him, wielding it as an instrument of revolution.

Author: Delphine Malosse. Translator: Tamsin Dearnley. Read the original article in French here.