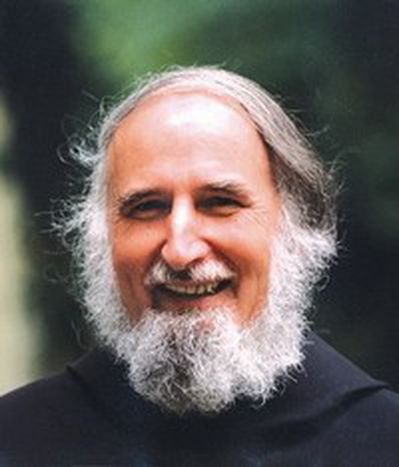

Anselm Grün: 'we should be asking ourselves what we can learn from Islam’

Published on

Translation by:

Claire McBride

Claire McBride

The Benedictine monk and author, 62, on splits within the Catholic Church, Islam plus dialogue and a humane globalisation

Far away form the noise of the city, in the middle of mountains and picturesque villages, the Münsterschwarzbach monastery towers majestically. The place has become a spiritual pilgrimage in the historic region of Franconia mainly because of Father Anselm Grün, a shy priest with a characteristic pointed beard. He has become something of a popstar of the Catholic Church in Germany. His esoteric devout works such as Finding Your Inner Balance ('Zur inneren Balance finden', Herder Spektrum, 2006) and A Happy Heart (aka 'Herzensruhe', Herder Spektrum, 2000), are bestsellers and have been translated in to more than 28 languages. Thanks to these works the Benedictine monk is counted amongst the most important and contemporary authors of spiritual literature around the world.

Father Anselm greets me early on a Saturday morning at the gates of the monastery and leads me – at my request – to the monastery’s only café, the perfect place for brunch. Surrounded by spiritual looking women however, a retreat seems in order: with a cup of tea we move to a quieter room next-door, where Grün begins to tell me about his life.

Now aged 62, he explains that as soon as he had completed his A-Levels he decided on a life as a monk, and joined the community of the Benedictine monks at the Münsterschwarzbach monastery. Not without scepticism mind you: ‘of course I had doubts in the beginning, I doubted whether life as a priest would be too restrictive for me. I wondered whether life without marriage was really possible and could I suppress my sexuality.’ Even today when he says that the decision for a religious life ‘proved to be my calling,’ he still has his moments of sadness: ‘Sometimes I find it painful that I have not been able to marry and have children’.

Father Anselm speaks softly and slowly, occasionally sipping his cappuccino whilst he talks about his time studying in Rome. His theological studies fell during the time of social change at the end of the sixties, when student protests in several European countries were demanding a better world. ‘At that time these feelings were being expressed even by us. We rebelled against the old customs and the fuddy-duddy rituals’ - for a church which preached more about issues relevant to the time and which made the people the main focus of its teaching and life.

Christian mysticism and modern psychology

This idea of being closer to the people characterises Grün’s work and is the foundation of his success. He connects Christian mysticism with modern psychology and far-eastern philosophy. ‘I have an easy language which isn’t valued,’ which he cites as an important reason for his success. A language which nevertheless receives criticism: in the conservative realms of the church especially, many fear a watering down of Catholic principles because of spiritual openness and the more liberal stance of Grün’s philosophy. ‘I speak a different language than many conservatives. I come into contact with many people in many different circles,’ he notes, somewhat embarrassed.

So is Grün an innovator, a forerunner even, of a small religious revolution? ‘I consider myself to be in union with the Catholic traditions,’ says the priest, avoiding the issue. When he speaks of Pope Benedict XVI, whom he has not met personally, the Benedictine monk is upbeat: ‘an opportunity has started under the new Pope. I don’t believe that he has anything against my theology.’

‘In this time of movement and change, young people are looking for stability and clarity,' says Grün, on the increasing appeal that the Catholic church has for young Europeans. 'Today’s youth are often not connected with the church and are curious about it. This is the best chance for the church to show that it is authentic and that it offers spirituality’, explains the theologian.

Striving for a big heart

The search for healthy spirituality is a central aspect in Grün’s theological work. ‘There are forms of religion that are sick and fanatical, not only in Christianity but also in other religions,’ he says with concern, on the tendency for religious fanaticism. Father Anselm has found the key to a holy, non-fanatical form of faith in the founder of the Benedictines: ‘For Bendictines from Nursia (after the first Saint Benedict of Nursia, founder of the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino), the sign of healthy spirituality is a big heart.’ A big, pure heart has openness, tolerance and a capacity for understanding and empathy.

And what about the relationship between the Catholic Church and Islam? 'On the one hand it is important to establish a good dialogue, so that we can both respect each other’s traditions,' says Grün rather hesitantly. 'However we still have to criticise intolerance which we still see in many Islamic countries. What we need is a critical dialogue.' At the same time, the Benedictine warns about the danger of projecting images of Islam as an enemy. Instead 'we should ask ourselves what we can learn from Islam,’ as he refers to the liberal Sufi tradition.

Father Anselm admits that even his own church is in no way free from intolerance. We speak about the Catholic church’s stance on homosexuality. ‘There are definitely dark sides here,’ says the theologian, deep in thought. 'It is particularly problematic when the Catholic faith is pulled up for discriminating against homosexuality which has happened in several eastern European countries. We have to make sure we don’t see homosexuality as a sin,’ emphasises Grün.

Father Anselm constantly refers back to his main principle of a big heart. With this idea he outlines the philosophy of humane globalisation. ‘If globalisation only benefits the strongest in society, then it will be a curse’. He appeals to the responsibility of a global economy, demanding ‘net product through high regard for one another’. In his regular management seminars, Grün teaches that business and management should be undertaken with an open heart, tolerance and with understanding and empathy instead of thinking of oneself all the time. ‘The aim is not to judge, but to be understanding’ - the principle commandment of the Benedictines.

This 'Brunch with ...' was first published on 2 July 2007 on cafebabel.com

Translated from Anselm Grün: "Homosexualität ist keine Sünde"