Animated Dreams in Tallinn: film articulates art and the market

Published on

Translation by:

Matthew PagettWhile the older generation of illustrators, working from former soviet studios, export their art thanks to public financing, the younger ones attempt to reconcile artistic creation and getting paid. The local festival kicked off on 19 November

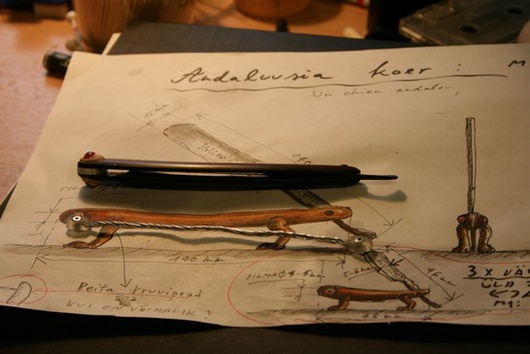

Vlan. A car door slams loudly in a blast of cold Nordic air. Depressing. In an old sock factory, at the end of a dark corridor filled with inanimate bodies, a small sign indicates the Nukufilm studio. A strange wooden character is suspended from the ceiling, a totem blackened by a candle. ‘This is the God of Nukufilm. Each time that a short film is finished, we light the candle, praying that he will have a long life.’ A blond head atop a deprecated sweater has just opened the door to what animated Estonian film does in its most artisanal and driven: puppet films.

History of a fight for independence

Nuku means ‘puppet’ in Estonian. With the cartoon-geared Joonisfilm, the studio represents the jewel of Baltic animated art. ‘Author's cinema,’ says Mait Laas, a director in his forties and child of a place that is both enchanting and dusty. He speaks of visual works, the former articulate stars of the big screen who now sleep in the windows of museums, and the efforts made by the studios to stay standing, after independence and the soviet retreat in 1991. ‘There is a very big tradition of animated film in Estonia. Our studio celebrated its fiftieth anniversary last year,’ he says. ‘We represent Estonian cinema in Europe, from the various artisan works to the latest technology. But without public money, we wouldn't exist.’

‘Refreshing’, ‘unusual’, ‘schizophrenic’... Estonians are often at a lack of words for accurately describing the universe that animates the films of this tiny little country in the north east of Europe. Poetic, sinister, definitely for adults, elaborately alive when the puppets suddenly appear, multicoloured or sepia, daring. And above all, unsellable! On a wall in the Nukufilm studios, a map of the world is dotted with drawing pins. In Europe, an army of points agglutinates. ‘This is the map of the festivals in which our films are shown,’ Mait says. ‘Without these trips in the European Union, favoured by the creation of networks like Anoba (Nordic and Baltic animation), and sometimes to the ends of the earth, there wouldn't be Estonian cinema. Short films don't go over well in theatres. And on TV, it's televised series for children that are hits.’ Author's cinema flourishes in craggy terrain.

‘Refreshing’, ‘unusual’, ‘schizophrenic’... Estonians are often at a lack of words for accurately describing the universe that animates the films of this tiny little country in the north east of Europe. Poetic, sinister, definitely for adults, elaborately alive when the puppets suddenly appear, multicoloured or sepia, daring. And above all, unsellable! On a wall in the Nukufilm studios, a map of the world is dotted with drawing pins. In Europe, an army of points agglutinates. ‘This is the map of the festivals in which our films are shown,’ Mait says. ‘Without these trips in the European Union, favoured by the creation of networks like Anoba (Nordic and Baltic animation), and sometimes to the ends of the earth, there wouldn't be Estonian cinema. Short films don't go over well in theatres. And on TV, it's televised series for children that are hits.’ Author's cinema flourishes in craggy terrain.

Unique plots

‘Somewhere in Europe, at the edge of a large sea, the village of Gadgetville’. In a colourful décor, several generations of little Estonians have on television the marvellous adventures of Lotte on television. She is a little dog girl with a palm tree on her head. Eesti Joonisfilm, the Estonian animation studio founded thirty-one years ago, counts on this flagship project to bring the necessary funds to artistic enterprises that are much more risqué.

For Priit Pärn, the most famous Estonian author, Lotte (and her spin-off products) is a mediocre provider for the ‘economic survival’ of the cartoon studio, one of the only ones in eastern Europe to have survived the end of the Soviet bloc. ‘The television channels explain to you what they expect from you. They impose too many rules, limits,’ he says straightforwardly. ‘We are such a small country, we can't fight on the terrain of mastodons and commercial series, those from the very large European studios,’ adds another director, Rao Heidmets, who revindicates his well-trained ‘crazy muscle’ with fantasy.

Priit Pärn is another teacher and founder, in 2006, of the Tallinn animation school. The 67-year-old holds dear his independence and freedom to write unique plots. In his most recent forty minute film, Life without Gabriella Ferri, a couple wrap themselves in a sticky, sensual dance, a fish in one hand, a knife in the other, whilst their child, closed up in his room, hits his head against the wall. Disturbing to say the least, and evocative of a menacing society where even family links crumble.

Priit Pärn is another teacher and founder, in 2006, of the Tallinn animation school. The 67-year-old holds dear his independence and freedom to write unique plots. In his most recent forty minute film, Life without Gabriella Ferri, a couple wrap themselves in a sticky, sensual dance, a fish in one hand, a knife in the other, whilst their child, closed up in his room, hits his head against the wall. Disturbing to say the least, and evocative of a menacing society where even family links crumble.

Let them eat

On the steps of the old guard of mad pencillers, the young artists of Tallinn also attempt risqué adventure. However they hope to leave precarity behind, which quickly becomes a synonym with creativity. It's simple: they want to earn their living. Manager Martin Rääk and his creative colleagues installed their lair in an old wooden house transformed into a design workshop. Thanks to a few good contracts signed with Estonian television, their small company, Tolm Studio, is on track.

On the steps of the old guard of mad pencillers, the young artists of Tallinn also attempt risqué adventure. However they hope to leave precarity behind, which quickly becomes a synonym with creativity. It's simple: they want to earn their living. Manager Martin Rääk and his creative colleagues installed their lair in an old wooden house transformed into a design workshop. Thanks to a few good contracts signed with Estonian television, their small company, Tolm Studio, is on track.

‘There is a place to take, between the old short films of Nuku, you know, the dinosaurs, and other activities that allow a company to function,"’ says Martin. ‘It's a dream to be able to dedicate ourselves only to our personal projects, but we hope to be able to alternate that with a developed commercial and visual activity,’ adds Joosep Volk, a young 27-year old director. And if possible, with a bit of humour: ‘When we Estonians try to be funny, it's always a failure. Our universe is depressing, because of our past.’

‘There is a place to take, between the old short films of Nuku, you know, the dinosaurs, and other activities that allow a company to function,"’ says Martin. ‘It's a dream to be able to dedicate ourselves only to our personal projects, but we hope to be able to alternate that with a developed commercial and visual activity,’ adds Joosep Volk, a young 27-year old director. And if possible, with a bit of humour: ‘When we Estonians try to be funny, it's always a failure. Our universe is depressing, because of our past.’

Nostalgic and sad, deep. The older ones don't hide it: ‘When I try to make a funny film, naive like they know how to do in the west, it always ends up being depressing!’ says Rao Heidmets. At the end of the month of November, now in the tenth year of Animated Dreams, the Estonian animation festival, ‘the animation gang will happily reunite in the old Cinema Soprus in the historical centre of Tallinn. It’s a family festival where it will be about fun; the bringing together of several generations, professors and students, schoolmasters and bad boys.’

Nostalgic and sad, deep. The older ones don't hide it: ‘When I try to make a funny film, naive like they know how to do in the west, it always ends up being depressing!’ says Rao Heidmets. At the end of the month of November, now in the tenth year of Animated Dreams, the Estonian animation festival, ‘the animation gang will happily reunite in the old Cinema Soprus in the historical centre of Tallinn. It’s a family festival where it will be about fun; the bringing together of several generations, professors and students, schoolmasters and bad boys.’

Many thanks to the cafebabel.com Tallinn team - in particular Giovanni Angioni

Translated from Cinéma d’animation : articuler l’art et la bourse