Alessandro Mannarino: 'Italian brains have been infantilised by television'

Published on

Translation by:

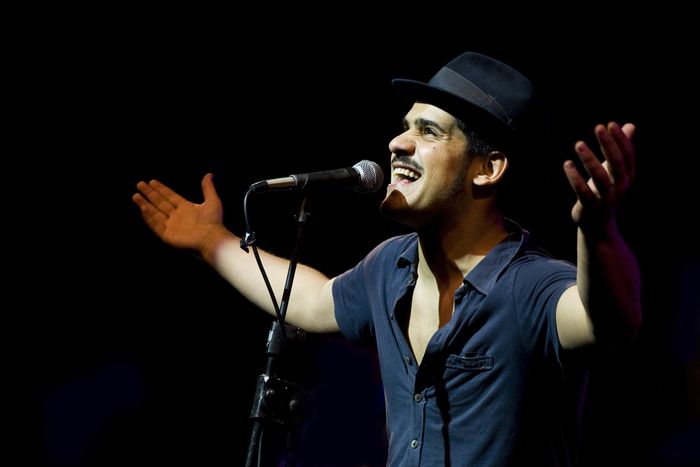

Sarah TruesdaleAn emerging talent on the Italian scene, the 30-year-old Roman combines poetry with sounds from around the world, shoots music videos in Roma camps and slams the way of thinking in his country

It’s four in the afternoon in San Lorenzo, an alternative multicultural neighbourhood which lies between Termini train station and the Verano cemetery in Rome. A silhouette familiar to those who have already seen this man onstage appears at the end of the road. Two black, curious and slightly astonished eyes sidle between hat and moustache, indicative of the style Alessandro Mannarino secretes.

Mannarino's alternative influences

Everywhere he goes the dimunitive star is greeted with cries such as 'Ale', well done, you're the best!' Only a year after the launch of his first album Bar della Rabbia ('Rage Bar'), Mannarino is already a star, and yet he pretends not to know it. The conversation quickly turns to the bar mentioned in his album title; this is part of his imaginary world, whose characters he incarnates onstage and who he sings about in his music. Prostitutes, alcoholics, sad clowns, charlatans, disappointed lovers: all find themselves at the Bar della Rabbia, where the wine flows. 'A glass of wine is always an excuse to let yourself go,' he begins, cradling his glass, 'to take off the mask that you wear every day. At the end of a long night of intoxication you can finally tell your own story and can perhaps paint yourself in a different light.'

Everywhere he goes the dimunitive star is greeted with cries such as 'Ale', well done, you're the best!' Only a year after the launch of his first album Bar della Rabbia ('Rage Bar'), Mannarino is already a star, and yet he pretends not to know it. The conversation quickly turns to the bar mentioned in his album title; this is part of his imaginary world, whose characters he incarnates onstage and who he sings about in his music. Prostitutes, alcoholics, sad clowns, charlatans, disappointed lovers: all find themselves at the Bar della Rabbia, where the wine flows. 'A glass of wine is always an excuse to let yourself go,' he begins, cradling his glass, 'to take off the mask that you wear every day. At the end of a long night of intoxication you can finally tell your own story and can perhaps paint yourself in a different light.'

A few hundred years ago, a few hundred metres away, Bacchus (Dionysus), the god of wine and intoxication, led Romans into dreamlike orgies; extreme outlets in somewhat tedious lives. In a Julius Caesar era, Mannarino himself would have been a bacchanalian DJ, entertaining the streets of Rome with music from the four corners of the earth. 'When I was twenty, I left home and spent the night wandering around Termini train station,' he continues. 'I started to get gigs as a world music DJ in bars populated by people of different ethnicities. That’s how I discovered ways of making music that were different to what I was hearing on the radio.'

Rome: its traditional music and Roma camps

Mannarino's musical universe and the melodies belonging to it found their voice in 'blues from Mali, klezmer music, Balkan music, in the bossa nova.' Mannarino also lays claim to the French cabaret artists and Italian cantautori ('singer-songwriter') and among all of these influences he has found a common rule. 'It’s a rule which exists in all popular and traditional music. Each song must carry in it a shock, a unique spark, which leaves an imprint, an idea.'

'The gypsies from Casilino 900 never did anything to hurt anyone'

But Mannarino's main source of inspiration is from his childhood. All of a sudden, his eyes sparkle and his moustache wiggles. His hand is under his hat, pushing back his hair, bringing back the memories. He remembers afternoons spent with his grandparents listening to traditional Roman songs. 'For me, Alvaro Amici and Gabriella Ferri were a bit like the gospel was to Ray Charles.' Mannarino put everything into a pressure cooker, waters it with nineteenth century poems from Trilussa, seasons it with the Roman dialect and pours the elixir into the streets of Rome. 'The Rome I sing about is the Rome of dreams, the Rome that I’ve lived, that I’ve walked, that becomes something different at night.' A distilled vision of an eternal city with two faces. The doorway to paradise for some, hell on earth for others. The gypsies of the Casilino 900 camp experienced the stigma of this two-facedness for years. Mannarino filmed his first music video for Tevere Grand Hotel in the biggest Roma camp in Europe. 'The gypsies from Casilino 900 never did anything to hurt anyone other than help a few more Italians see different clothes and different jewellery at those campsites through different eyes.'

Alessandro Mannarino, the anti-activist

Alessandro rejects the behaviour of the activist musician and refuses to become involved in politics. Before helping others he says he must help himself and that 'that’s a good start.' On his list of things which make him happy is, as soon as he creates a song, to repeat it 'twenty, thirty times over again' because it moves him and makes him dream. Then, it's about having fun live. 'Going onstage is a bit like living a dream,' he says. 'The lights go out as if you’re closing your eyes and entering into a different reality. If a song makes me dream, it can also make someone else dream.'

Alessandro rejects the behaviour of the activist musician and refuses to become involved in politics. Before helping others he says he must help himself and that 'that’s a good start.' On his list of things which make him happy is, as soon as he creates a song, to repeat it 'twenty, thirty times over again' because it moves him and makes him dream. Then, it's about having fun live. 'Going onstage is a bit like living a dream,' he says. 'The lights go out as if you’re closing your eyes and entering into a different reality. If a song makes me dream, it can also make someone else dream.'

When he's back on earth, Mannarino tries to avoid the pitfalls that come with quick success. Money is not a problem for him. 'I know how to live on very little and if I don’t have any money, I go and make some.' Nor does he believe that money is Italy’s problem. 'The problem with Italy today is way of thinking. In the last ten years, Italians’ brains have been deliberately attacked using television; they have been infantilised, numbed by sterile programmes, presented with representations of life as if it were a product, where anything is possible, where no-one does anything bad.' He finishes his glass. 'But it’s not like that. It’s not like that! And everyone knows that all too well.'

Bar della Rabbia (2009) was nominated for the Tenco Prize for Italian music (new talent category). Mannarino’s next album will be out later in 2010

Images: main image ©Sonia Maccari; ©Simona Mizzoni ; ©Mathilde Auvillain

Translated from Alessandro Mannarino : «qu’importe la chanson, pourvu qu’on ait l’ivresse»