Albanophobia: land for Harry Potter villains?

Published on

Pop culture won’t cease to derive from stereotypes and prejudice. One Serbian journalist, who tentatively packed her bags for Tirana, finds out whether this is a revealing sign of ever-present albanophobia or anti-albanianism

Throughout the Harry Potter books the evil villain Lord Voldemort flees to a land called Albania on several occasions; it’s a place covered with dark forests and which is full of evil creatures. If you skipped British writer J.K. Rowling's franchise and watched mainstream Hollywood action movies (we’re thinking Casino Royale in 2006 or Taken in 2008), Albanians become the masters of criminal organisations. Whether it can be considered as an authentic term in social sciences or not, 'albanophobia' has made it as an expression onto the pages of Wikipedia and 2010 eponymous Anglo-Saxon paperbacks. The general definition of it is towards Albanians being ‘criminal and degenerate: albanophobia or anti-albanism is ‘more widely spread in countries that have large Albanian ethnic minorities, such as Serbia, Macedonia and Montenegro and in countries with numerous Albanian immigrants, like Greece and Italy’.

Getting Belgrade closer to Tirana

I experience some of that phobia while booking a ticket for a flight from Belgrade to Tirana; seems to surprise my travel agent. There is no direct transport from the two capitals. A direct flight operated by the Serbian airline JAT was cancelled in 2008. Other ways of travelling to Tirana include going to the city of Ulcinj in Montenegro and taking a mini van or a cab from there, or to go to Prishtina (which a lot of Serbs are still afraid to do) and take a bus from there. I end up flying via Rome for around 200 euros. Whilst packing my bags I receive more calls than usual from friends and family with one recurring sentence: ‘Be careful while you're in Tirana’ - despite the fact that none of them have actually travelled to Albania. The negative stereotypes about Albanians have been deepened in Serbia by Swiss council of Europe rapporteur Dick Marty and his report on Serbian organ trafficking by Kosovars in Albania in December 2010. It's ticked the Albanians off too: most recently, a libel suit against the claims by an Albanian family was dismissed in June 2011.

'Whilst packing I receive more calls than usual from friends and family with one recurring sentence: Be careful while you're in Tirana’

It's in the fields of culture and science these prejudices are best overcome. In 2010 universities in Tirana and Belgrade signed a cooperation agreement which welcomed Albanian guest lecturers at the department of albanology in Belgrade.Merima Krijezi, departmental assistant, says relations between the two countries are taking a positive pace after a long period of stagnation. ‘The media in Albania have a positive attitude,’ she explains. ‘In the Serbian media there isn't that much information about it. For instance, when the Belgrade national theatre played in Tirana, the Albanian media reported on it but an Albanian string quartet visiting Belgrade didn't receive much media attention.’

Ottoman and Greater Albania

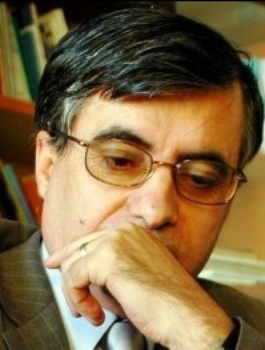

To my surprise, professor Shaban Sinani can speak a bit of Serbian. The Albanian researcher is specialised in ethnology and regional issues, and contextualises that all kinds of xenophobias in the Balkans were born with the creation of the first borders in this region. ‘During the Ottoman empire there were no borders and no misunderstandings between the Balkan people,' he tells me at Tirana international hotel. 'That was the only good thing about the reign.’ Sociological surveys on ethnic distance in Serbia show a high level of animosity towards Albanians. For example, whilst the Road out of brotherhood and unity - ethnical distance of citizens of Serbia study, published earlier this year, cites that the ethnical distance toward Albanians is slightly decreasing, results showed that 70% of interviewed wouldn't want to get married to an Albanian. Those relations are apparently not an issue in Albania at all. It's quite the opposite. ‘People here, especially young people, don't really have a formed opinion about Serbia because they generally don't know a lot about it,’ says one young Albanian.

To my surprise, professor Shaban Sinani can speak a bit of Serbian. The Albanian researcher is specialised in ethnology and regional issues, and contextualises that all kinds of xenophobias in the Balkans were born with the creation of the first borders in this region. ‘During the Ottoman empire there were no borders and no misunderstandings between the Balkan people,' he tells me at Tirana international hotel. 'That was the only good thing about the reign.’ Sociological surveys on ethnic distance in Serbia show a high level of animosity towards Albanians. For example, whilst the Road out of brotherhood and unity - ethnical distance of citizens of Serbia study, published earlier this year, cites that the ethnical distance toward Albanians is slightly decreasing, results showed that 70% of interviewed wouldn't want to get married to an Albanian. Those relations are apparently not an issue in Albania at all. It's quite the opposite. ‘People here, especially young people, don't really have a formed opinion about Serbia because they generally don't know a lot about it,’ says one young Albanian.

One other reason that albanophobes use to justify their fears is the plan for creating a Greater Albania. The term was widely used in the Serbian and Macedonian media during Kosovo's claim for independence from Serbia and during armed conflict in Macedonia in 2001. Greater or Ethnic Albania is a term that includes territories in the region mostly populated by ethnic Albanians (Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia, Macedonia and Greece). Professor Shaban Sinani shakes his head vigorously. ‘This term was not created by Albanians,’ he emphasises. ‘It was a creation of nazi fascists, by Mussolini and the Third Reich. For sure, there is no project for Greater Albania anymore.’ Though this is an abuse of history in modern politics, a 2010 Gallup poll carried out in cooperation with the European Fund for the Balkans, cited by Macedonian TV Kanal 5 conducted in 2010 shows that a large number of Albanians support the idea of Greater Albania.

Don't forget the Greeks

Meanwhile, an upcoming registration initiative shows that Albanians have their own similar fears toward Greeks in the south of their country. A popular census coming up in November 2011, The Red and Black Alliance, has started an initiative to collect 50, 000 signatures in order to ban questions on nationality and religion from the registration form. In a café not very far from the point for petition signing in the downtown of Tirana, activist Endrit Shabani expresses his fear of wrongful national declaration during the registration. Although questions on nationality and religion are normally included in other European countries’ registration forms (but are not obligatory to respond to), in Albania they haven’t been asked during the popular census for over seventy years. Thus there hasn’t been any recent official exact data on the number of minorities in Albania. '30, 000 poor families in the south of Albania get some sort of pension from Greece,' explains Endrit. 'If they don’t declare themselves as Greek, they won’t get that financial help any more. On the other hand, if they do declare themselves to be Greek, it’s going to bring up ethnic tensions in Albania. The registration is supposed to be a statistical process, not a process that can cause legal implications. But thanks to the law on registry that our government has adopted, every self-declaration stated in the registry will not have to be proved and will overlap data in personal documents, such as a passport.'

Whilst the Balkans may be known for nationalistic disputes, Albania as a country has managed to stay out of it. The main focus since it emerged from communism in 1991 has been accession to the European union. In fact, Albanians have shown the highest rate of euro-optimism in the region. As for albanophobia, according to Gallup research carried out earlier this year, more than 60% of Albanians are convinced that the image of their country is positive and improving within the EU; far from what the Dark Powers of today's literature might have us think.

This article is part of cafebabel.com’s 2010-2011 feature focus on the Balkans - read more about the project Orient Express Reporter and read articles from the mission here

Images: main imdb Casino Royale official still; Prof. Dr. Shaban Sinani courtesy of official facebook page; campaign image from The Red and Black Alliance