AKW Lobau: Vienna caravan communities away from it all

Published on

Translation by:

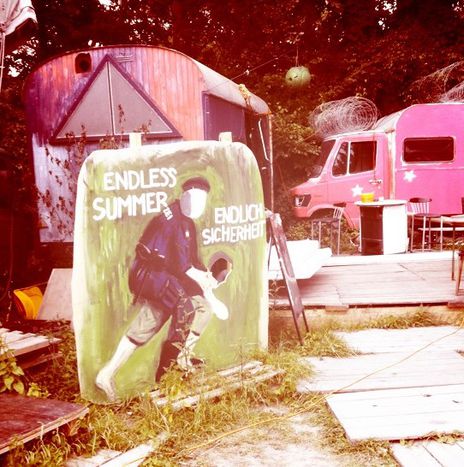

Annie RutherfordThe story of the caravan commune AKW Lobau demonstrates that Vienna is not nearly as bourgeois and narrow-minded as is always claimed. The community is living proof that alternative enterprises do have their place in the Austrian capital. A flying visit

Coffee is served with soya milk. With a broad grin on his face, Hans throws the old hose into the circle where his ‘flatmates’ are sitting. He has just built in a new 'safe to drink' hose. The others try out the now much more digestible drinking water. Hans has also bought molding plaster and brown paint. The community of the Vienna caravan commune AKW Lobau wants to start up an egg competition soon. The aim is to make and paint plaster eggs; because while the commune’s free range hens do lay eggs here and there, it's always hard to find them. The hens were Harald's idea. ‘Harald the hen-herd’, his mates tease the 23-year-old geography student, who has lived in the commune for quite some time.

Paying rent according to car length

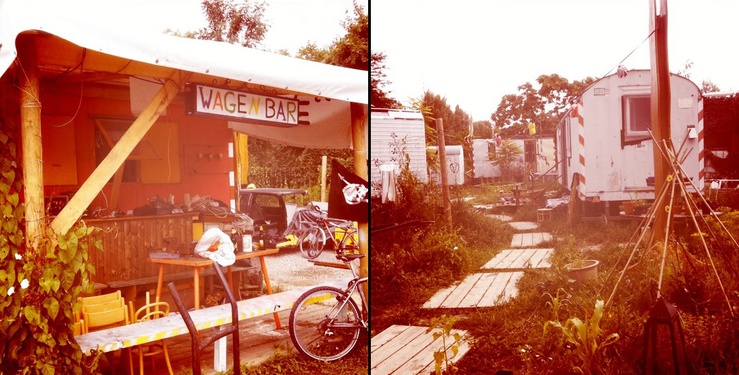

The story of the Vienna caravan communes started in 2006, when Martin, a 35-year-old psychology graduate and one of the commune founders and a few friends simply parked their caravans permanently in the industrial estate. The problems this caused were of course to be expected, as ‘permanent residency’ is illegal in the green spaces in Vienna. They had to leave, and they moved time and time again, until a year ago, when Vienna council rented them the plot in Lobau – entirely legally. Today about twenty vehicles, all as different as their inhabitants, are parked in the Donau-Auen national park in the the east of Vienna. Just as the price of bread in the famous Vienna cafes is based on ‘centimetres’, inhabitants pay rent according to the ‘length’ of the car. Otherwise there aren’t any rules – except for the plan for cleaning the toilet. Everyone is welcome. A few years ago an Irish guy even turned up by bike – and stayed.

The AKW Lobau is a kind of large shared flat, but out in nature – a motley and colourful mix of young people who don’t want to live according to the confined and often overly expensive conditions in the city. Harald calls it the ‘opening the door and standing in a meadow’ feeling. He even puts up with the half-hour bike ride to university because of it. ‘Being able to stand right in the middle of nature and encroaching relatively little on the environment,’ are the reasons that car mechanic Patrick gives for his decision to be part of the alternative life here in the commune. The community members grow their own vegetables. They try to live without using up too many resources but avoid being green idealists. Hans even installed solar panels on the roof of his caravan at the entrance, so that at least in summer he can create the necessary amount of electricity. Moritz comes to join us and bangs a bucket of full tomatoes down on the wooden table standing outside. He has fished them out of the bins of the nearby supermarket, a lifestyle trend called containering or freecycling. The tomatoes that are still good are set aside to be eaten, whilst the rest are reserved for a bloody mary shower for the Dutch member James’ birthday. Patrick says that he learnt here to live together 'according to the smallest common denominator’. Harald adds that he learnt how to ‘deal with conflicts’.

Bulldozer for breakfast

For the average city-dweller who sees the narrow, windy path leading past the different caravans, the trampoline and the communal bathroom, the idyll of the community seems complete. Moritz’s drumbeats sound from the music van but otherwise it is fairly quiet on the Friday that I visit. The hens are basking in the last sunbeams of the day. Yet this is all just an illusion because a large construction site is located very close by. Vienna city council wants to build a canal here in the next three years. The commune’s lease is also for three years. It’s understandable that the group feels cheated. No-one had expected a daily dose of pneumatic drilling for breakfast. The group still pays 10, 000 euros (circa £8, 700 pounds) rent annually.

Complaints from the neighbours, stirred up by local politicians from the right populist party the FPÖ (the freedom party of Austria), are also increasing - at least in the media. The community newsletter talks about noisy anarchists who mess up the surrounding area. However the group’s communal toilets are sparkling clean; cleaner than many public toilets. There’s even a bidet.

Meanwhile the information on the FPÖ website Wagenplatzstopp.at (‘stop caravan communities’) isn’t accessible anymore. ‘The communes are mainly in areas where there aren’t any neighbours,’ remarks David Ellensohn, chairman of the Vienna green party. ‘In the eyes of the FPÖ these are leftist radicals who are probably planning terrorist attacks. The FPÖ are tough guys who get scared whenever someone wears a headscarf or lives in a commune. They are scared of everything which is different.’ Alternative culture does have an indisputable value in a town which, like Vienna, is often dismissed as irretrievably middle-class. This is particularly the case now that the green party is on the city council. According to Jutta Kleedorfer who works for a better, creative use of Vienna’s living spaces, ‘the squatters have become a symbol for freedom, for people who are part of the image of the city and who stubbornly campaign for a local community.’ There have even been tours to the Lobau commune in the past.

Figurehead of a Vienna subculture?

‘There just isn’t enough political will in Vienna,’ laments Martin, co-founder of the commune. There is no tradition of caravan communes here the way there is in Berlin or Spain. According to Ellensohn, the greens are nevertheless planning a law for 2012 which should enable temporary residency. ‘At the moment we are working with stopgap solutions, we do need to provide better security for the future,’ the politician admits.

‘We have bought ourselves the peace and quiet’

Nobody in the commune is thinking tonight about new laws from far-off Vienna. A hip-hop band is now playing where the table had been standing this morning, while an electro DJ is presiding over what is normally an improvised football field. The community is holding a caravan park party. There is beer from the caravan bar and home-made cocktails. On the old backseat of a car people are smoking, while a fire is flickering in a container next to the dance floor. This is far from the Viennese stereotype of a narrow-minded petty bourgeoisie. But you do have to travel quite a way out of the city to experience a bit of Vienna alternative culture. ‘We have bought ourselves the peace and quiet,’ says Patrick.

How long the peace will last until the next eviction notice is hard to say. Another Vienna commune ‘Treibstoff’ (‘fuel’), who are currently parked on a plot at the Prater, have a contract until 31 August before they will be threatened with eviction. The caravan commune’s modern nomadism will just keep going until long-term solutions can be found in Vienna.

This article is part of cafebabel.com’s 2010-2012 feature focus on Green Europe. Read the official blog from the cafebabel.com team in Vienna

Images: Vintage © Katharina Kloss; Rest © Anne Lore Mesnage; video: (cc) haudraufundhauab/ Youtube

Translated from Von wegen weg mit den Wiener Wagentruppen