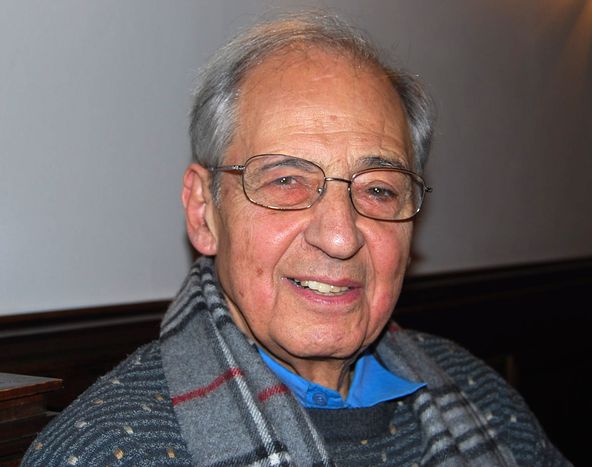

Agop J. Hacikyan: 'I don’t feel I am translating my culture into English'

Published on

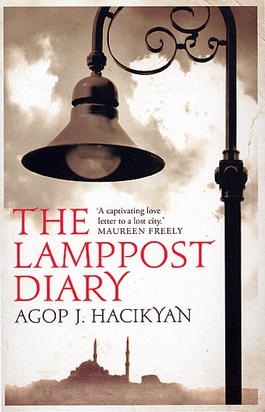

The playful Armenian-Canadian author talks his latest novel - hailed as a 'love letter to Istanbul' - straddling continents and his opinions on Turkey in the EU

The Lamppost Diary is hard to put down. The coming-of-age tale, set in Istanbul against a backdrop of the Armenian genocide of 1915 and the second world war, masters the clean fluidity of an author in control of every element of his work, without sacrificing the imaginative contribution of the reader. 'When you write fiction, you are free, you can exaggerate, enhance the event, and this was a writing where I felt very, very free,' explains Agop J. Hacikyan, his blue eyes glimmering with alertness. 'No matter what you write, there is always some sort of autobiography. In everything.'

Turkish is not the question

It's a few weeks before christmas when I meet Hacikyan in a cafe opposite his publishers in Westbourne Grove, London. The clink of tea cups and his smile are a welcome relief from the street outside, which is throbbing with festive hysteria. Hacikyan reveals that the novel initially began as a short story: in the first chapter, a seven year-old Tomas is told about the sudden death of his sister by a priest at his English and American school. But she had died one month before; his parents had not wanted to break the news. His ever-present smile momentarily extinguishes. 'You know, when something is sad, sadness can turn into the joy of art, usually.' The reader accompanies the protagonist throughout: Tomas growing up in Istanbul with his Armenian parents; Tomas and a teenage brush with terrorism; Tomas' stab at journalism; and Tomas abandoning Turkey for Canada. It's not unlike Agop himself, who, after successfully completing the first year of his engineering degree, also left Turkey to pursue his literary dreams, returning to settle in Montreal in 1957, after other spells in New York and a PhD in London.

It's a few weeks before christmas when I meet Hacikyan in a cafe opposite his publishers in Westbourne Grove, London. The clink of tea cups and his smile are a welcome relief from the street outside, which is throbbing with festive hysteria. Hacikyan reveals that the novel initially began as a short story: in the first chapter, a seven year-old Tomas is told about the sudden death of his sister by a priest at his English and American school. But she had died one month before; his parents had not wanted to break the news. His ever-present smile momentarily extinguishes. 'You know, when something is sad, sadness can turn into the joy of art, usually.' The reader accompanies the protagonist throughout: Tomas growing up in Istanbul with his Armenian parents; Tomas and a teenage brush with terrorism; Tomas' stab at journalism; and Tomas abandoning Turkey for Canada. It's not unlike Agop himself, who, after successfully completing the first year of his engineering degree, also left Turkey to pursue his literary dreams, returning to settle in Montreal in 1957, after other spells in New York and a PhD in London.

The independent Telegram Books, based in London, San Francisco and Beirut, has always championed the works of more oriental writers. Agop shakes off my attempt to pin a specific 'regionality' onto him. He writes in English,although in the past he has also written in French. So how does Agop feel about discussing specifically Turkish themes to an English language readership? 'Like any British-speaking writer who has written about subject on many other cultures,' he says. 'But I know about the culture I am writing about, I know it very well and I don’t feel any difficulty in that. I don’t feel I am translating my culture into English; I am writing about something which is what I am and what I know and what I see and this is it.' He swats away a question on how Turkish he feels. 'You have your culture but it is influenced by so many things; I married a French, my children are half-French, half-Canadian and my daughter has married a Colombian - so you tell me what I am now!'

Europe knocking on Turkey’s door

Agop's career spans forty publications; his previous novel A Summer Without Dawn (2000), on the Armenian people's struggle during world war one, was translated into seven languages. Yet despite this worldliness, Agop maintains a mischievous humour and refreshing sense of purpose in his attitude towards writing: a writer must have a certain ideology and philosophy, but also must entertain. 'Your ideology will never be as strong as when you put it through an interesting narrative. Then [people] read, they don't feel they are being lectured. Otherwise they can read a newspaper.' Hacikyan reads widely in English, French, Turkish and Armenian, and he counts Paul Auster, Philip Roth, Milan Kundera and William Saroyan, an American poet, also of Armenian descent, as some of his most obvious inspirations.

'Your ideology will never be as strong as when you put it through an interesting narrative'

Throughout the novel there is a sense of Europe knocking on Turkey’s door and Turkey resisting this approach and trying to maintain its neutrality and at the same time, stifling Turkish ethnic minorities. Silence is a constant presence in the novel; from older generations of Armenians frightened of discussing the genocide with their children, to the freedom of expression. As a young university student, the protagonist Tomas sets up a literary journal for Armenian writing, which then runs into problems. Today, there are 70, 000 Turkish-Armenians, the largest non-muslim minority group. Agop is fairly brief on the topic of whether future generations must confront this silence in order to successfully become part of the EU. 'That will be a long, long process,' he says, his face acquiring an almost nostalgic expression. 'When I write about Turkey, there is an influence of the place where I was born and the mentality. There is an unconscious interference in writing and its terribly good for us.'

In Agop's mind, it is impossible to detach oneself from your past and background; a writer feels they have to write something new. 'But its absolutely impossible, everybody has got a background!' he exclaims. 'You, your parents, your environment, your schooling - it's always there.' Perseverance is the keyword of advice that Agop passes on to other, younger writers. 'Also I would insist that a good agent can create miracles! Even when you are established,' he adds. A whiff of bleach curls around us; the café is shutting shop. 'I am very very lucky to be able to do what I have always wanted to do,' says Agop, his eyes twinkling again as we get up to leave.