Aged three, Prishtina dances, designs but doesn’t debate

Published on

Kosovo is one of the most optimistic countries in the world with 70% of the population under the age of thirty. Music, bars and art dot my four days in its capital, Prishtina, three years after the city claimed independence from Serbia

It’s 17 February 2011 and Kosovo is three years old. The main pedestrian streets in the city centre brim full of people promenading. It’s like an image from a 19th century novel whose characters walk around to see and be seen. From the stage at the top of the street there are some sporadic programmes, such as a folklore ensemble in the early afternoon of children performing national dances in traditional costumes. Bands of drummers move along the street, animating the city’s men into dance.

Contemporary art scene in Kosovo: more dialogue!

The more cultural Prishtinali mingle in bars like Dit’ e Nat’, Kosovo's first bookclub hidden behind the Skenderbeu statue in a small sideway street off the central pedestrian street. Like Kriterion in Sarajevo, they are part of the organisation which participates in the international 4 tuned cities independent film and visual art festival. Low music in the background allows people to talk quietly in various languages. The surrounding walls are filled with mostly art, philosophy and social theory books in Albanian and English. If you are alone, maybe the bar’s cat will accompany you. However I am joined by young artists, including Majlinda Hoxha, who spent eleven years out of her country. ‘I’m very optimistic about the art scene now. It is being born,’ she says.

Art production remains traditional in a new-born country with such a deep trauma in the recent history. But considering Kosovo’s political, social and ethnic situation, I was not expecting a complete absence of engaged cultural and artistic practices, though Prishtina does hold some interesting installation and performances. ‘Young people and artists do not want their work to be characterised as political,’ explains conceptual photographer Majlinda Hoxha. In Kosovo politics is seen as something bad, representing the conflict and war. One part of the 2008 German federal cultural foundation publication Leap into the City is dedicated to the current state of culture in Prishtina, where Shkelzen Maliqi says ‘contemporary arts seen through its content seems very critical and reflects on something topical. In that sense contemporary art is very political.’ If the Kosovar philosopher and art critic is right, then why does nobody want to accept or acknowledge such determination?

Kosovo 2.0

Mejlinda Hoxha calls it a problem of disconnectedness. ‘It’s the result of the lack of criticism and theoretical analyses which would encourage communication between them, establish a base and induce creation of connections,’ she says. The contemporary artist Anita Baraku mostly produces installations and ‘action art’, and has seen many active female artists. ‘That scene is getting stronger,’ she adds, ‘but something like that has never been opened in a discussion. The critical scene here is very weak and inconsistent which is why it is very hard to have things analysed, systematised and given a bigger picture. There have been no public discussions in almost five years.’ The problem of the disconnectedness of actors on the visual arts scene rises from the lack of financial means which would provide sustainability for actors. Instead of networking, they compete. But there is a light at the end of the tunnel because the scene is very vibrant and has quite a lot to offer.

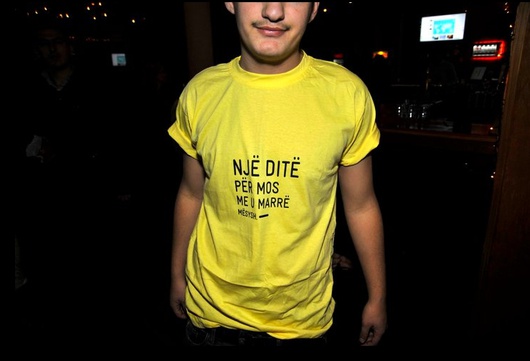

The Tingle Tangle bar in the city centre is run by programmers of the cultural space Manipulative Space Tetris. This alternative bar plays post rock music, is semi-lit with naïve drawings on the wall and shabby-girly decoration to warm you up and entice a familiar atmosphere. These new spaces, breathing with young and positive energy, hold the potential to encourage cooperation among their audience. Physical space has one potential, though the other is hidden in the virtual ones. ‘Kosovo youngsters are extremely active,’ says Eliska Slavikova who is at the bar. ‘They are much more open in the space of social networks.’ Kosovo 2.0 is one example of rather a small number of activists, progressive and eloquent young artists and thinkers.

The Tingle Tangle bar in the city centre is run by programmers of the cultural space Manipulative Space Tetris. This alternative bar plays post rock music, is semi-lit with naïve drawings on the wall and shabby-girly decoration to warm you up and entice a familiar atmosphere. These new spaces, breathing with young and positive energy, hold the potential to encourage cooperation among their audience. Physical space has one potential, though the other is hidden in the virtual ones. ‘Kosovo youngsters are extremely active,’ says Eliska Slavikova who is at the bar. ‘They are much more open in the space of social networks.’ Kosovo 2.0 is one example of rather a small number of activists, progressive and eloquent young artists and thinkers.

At the Kosovo national theatre the Bosnian musician Damir Imamović performs traditional songs from the region in a concert co-organised by the Heartefact Fund (HF) and assisted by the Youth Initiative for Human Rights’ activists. Sevdalinka is a music characterised by its melancholic tone and moderate rhythm, usually expressing deep sadness. Imamović speaks partly in English and partly in the Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian-Montenegrin language which is understood by the majority of audience. It’s not unimportant; in the streets in and especially outside of the capital, it is not recommended to speak these languages as a consequence of deep ethnic friction. The relief from this constant subconscious caution disappears into the ambience, creating an exhilarating atmosphere. ‘The theatre hasn’t been as full in years,’ beams a lady next to me.

Dit’ e Nat’, Fazli Grajçevci, 5, Prishtina 10000

This article is part of cafebabel.com’s 2010-2011 feature focus on the Balkans - read more about the project Orient Express Reporter

Images: main, cafe in-text © courtesy of dit' e nat'; branded T-shirt courtesy of Kosovo 2.0