Afterbabbel: All Ears

Published on

Translation gives you two poems instead of one. What could be better? Twice as many opportunities for possible 'ah's and 'oooh's as well as scrunching of the nose. Welcome to 'Afterbabbel', christened after the final chapter’s title in David Bello's splendid book on translation Is that a Fish in Your Ear.

Because we love what poetry does, as well as what happens in translation, Afterbabbel takes the form of reviews in dialogue. First we read the book, a collection of poetry from anywhere in the world, translated into English, then we meet over a cup of coffee, sometimes over Skype, always in different locations. Then we babbel.

Book: All Ears by Ludwig Steinherr

Translator: Paul-Henry Campbell

The gist of it: playful philosophical poems with surprising extended metaphors. Lots of exclamation marks.

A favourite quote: ‘Stars are sober creatures, but the paper napkins are dreamers.’

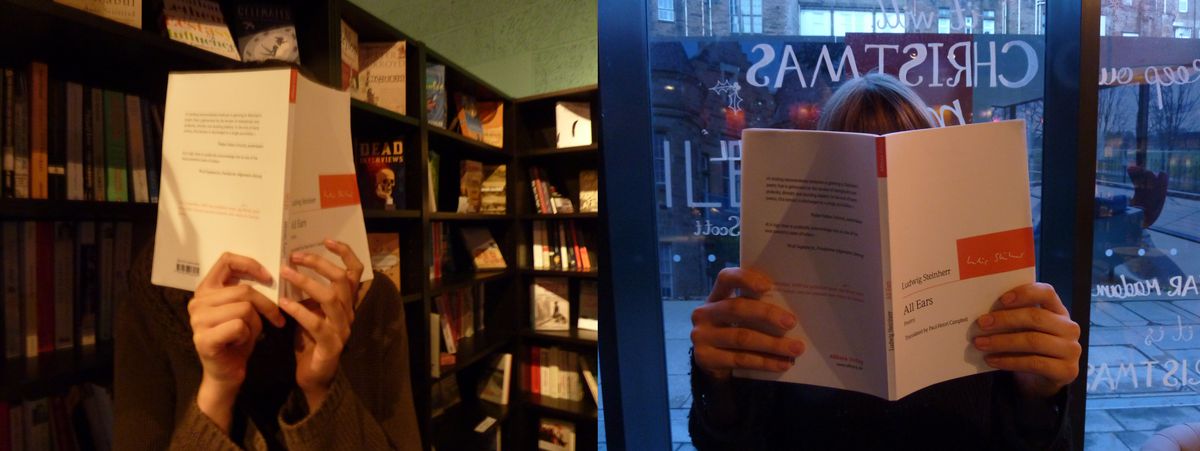

Discussed at: Looking Glass Books, Edinburgh

Jessica: Are there religious poems in All Ears, do you think?

Annie: I think there are philosophical poems. It depends how you deal with things like ‘the body of Jesus’. Take Philip Pullman’s The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ. I would say that’s not religious, although it’s a religious theme.

J: That’s true. Pullman’s novel is part of the Canongate myth series, so he basically treats the Christian story as one of many, many myths. I feel that this is the case with Steinherr’s poetry as well. After I’d read the whole collection I found myself writing a list of all the characters that were in there. There are loads of them – historical figures like Nero, as well as gods and goddesses from Greek mythology. And then there’s Jesus. Steinherr uses all of these communal stories as vessels for what happens in the poems.

A: He doesn’t treat Christian concepts much differently to ideas from classical mythology. And although classical mythology was a religion, you’d no longer describe it as “religious”.

J: Yes, you talk about Greek mythology as stories – that’s myth. What Philip Pullman does, and what Ludwig Steinherr does, is to put Christian symbols and narratives on the same level as those stories and treat them as myth.

J: What do you think about exclamation marks?

A: I got so annoyed with the exclamation marks! That was one of the reasons I wanted to see a German copy, to see whether they’re matched by exclamation marks in the German original, or whether they simply work in the original. There’s an overuse of exclamation marks – they made points which were good points seem trite.

J: I agree. When I started seeing them, I just thought, Oh God, please stop. There are a few poems in which I think it works. ‘The Sudden Jolt of Autumn’ is made up of four sentences all ending in exclamation marks. That makes sense because it’s at the heart of the whole poem. It’s very short and it’s about shouting. Yet in some poems, say ‘The Senusuous the Utmost Abstractness’, I thought, ‘Why are you shouting at me?’ I think the best poems in the book are the quietest ones.

A: My favourite part of the book is the one line poems in the fortune cookies chapter at the end. I loved ‘Every triangle is lonesome and kisses its own elbow.’

J: Yes, I’m definitely going to read those again. I wanted to write those down and put them around the house. ‘Listen to your umbrella, it is versed in the language of shadows.’

A: I loved ‘The shortest distance between two points is God,’ which I suppose is religious; it absolutely captures the way faith bridges gaps.

J: The fortune cookies say a lot about the rest of the poetry.

A: Yes, they feel like condensed versions of the other poems.

J: They work so well when they’re just single lines. That was something I found difficult with parts of the book. You find yourself asking, why is this a poem? There are so many images which are almost independent, if that makes sense.

A: It does. ‘The Sudden Jolt of Autumn’ was one of my favourite of the longer poems, and it shows what Steinherr does wonderfully: this juxtaposition, the extended metaphors of two images which are absolutely stay together.

J: Are welded together, even.

A: Yes, and that gets lost when the poems bring too many images in.

J: I like this poem, ‘Maybe Gold’. It’s just lovely. And it doesn’t have any exclamation marks! Was there anything that annoyed you about the poems, other than the exclamation marks?

A: I sometimes felt they didn’t need to be so explicitly philosophical. I like the philosophical in them – but you don’t need to put the word ‘metaphysical’ in there for us to understand that it’s metaphysical. That can have a bit of a distancing effect.

J: Whereas poems like ‘Maybe Gold’ work so much better. You see the images, instead of reading ‘the metaphysical shone through the bark’.

A: I do really like the first poem, which imagines furniture coming to life. It’s a very playful, philosophical poem and that works.

J: Maybe it’s to do with humour.

A: I think quite often the philosophical in the poems is humorous but sometimes the humorous isn’t quite strong enough. Maybe that’s a translation thing, perhaps it comes across better in German.

J: Yes, it might be.

A: There were a couple of things where I would have liked to see the original: ‘in’ and ‘into’ seemed to be muddled up for example, and in German the difference is shown through different cases, not different words. There was also one point where something was in the continuous past tense and it felt odd. German doesn’t have the continuous past tense, so I wonder if there was a particular word that prompted that translation?

J: Yes, that’s interesting – the way you can feel that kind of thing in translation. Do you know, there’s this one chapter title, ‘Schneewendeltreppe’. [Although the book is entirely in English, the chapter titles are also given in German - ed.] That’s much, much better than ‘Spiral Staircase of Snow’. Why don’t we have composed words in English?

A: What do you think Steinherr would look at, what would he notice in Looking Glass Books?

J: I think he’d mention the writing on the window.

A: The fact that it’s not writing on the wall, perhaps?

J: It’s like writing on the wall. But transparent – or something.

A: What’s transparent? Knowledge? Communication?

J: Language.

A: Which is actually a wonderful metaphor for translation.