Afterbabbel: A Rug of a Thousand Colours

Published on

Translation gives you two poems instead of one. What could be better? Twice as many opportunities for possible 'ah's and 'oooh's as well as scrunching of the nose. Welcome to 'Afterbabbel', christened after the final chapter’s title in David Bello's splendid book on translation Is that a Fish in Your Ear.

Because we love what poetry does, as well as what happens in translation, Afterbabbel takes the form of reviews in dialogue. First we read the book, a collection of poetry from anywhere in the world, translated into English, then we meet over a cup of coffee, sometimes over Skype, always in different locations. Then we babbel.

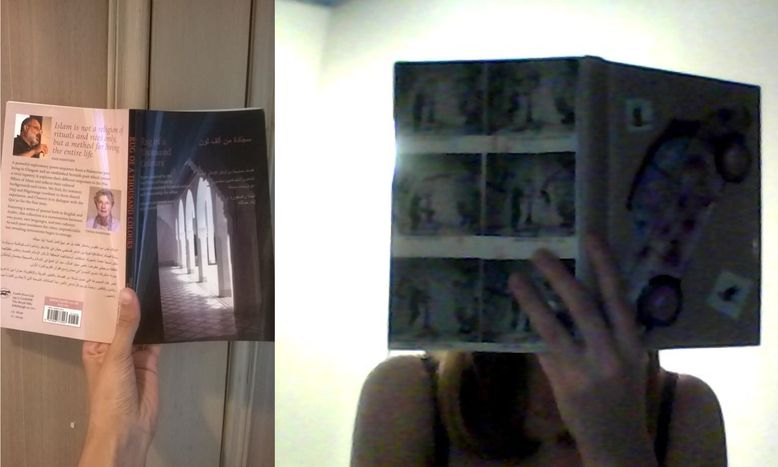

Book: A Rug of a Thousand Colours by Tessa Ransford and Iyad Hayatleh

Translator: Err, Iyad Hayatleh and Tessa Ransford...

The gist of it: A Scottish poet and a Palestinain poet now living in Scotland write poems based on the five pillars on Islam and translate each other's work into their own language.

A favourite quote: 'Cleanse my soul for thirty days with the beauty of forbearance/and let me reach the day of Eid/a new person, with a new dress.'

Discussed: over skype, in Edinburgh (UK) and Göttingen (Germany)

Annie: What do you think is the effect of having everything in both languages? Not just the poems but the introduction, prologue and essay at the end of the book?

Jess: Well it all comes down to the question, can you read both languages? As neither of us is able to do that, you know from the outset that you are going to be almost shut out from half of the book. You have to be constantly aware that here are things you will miss. I like how, even though it is published by Luath in Scotland, it’s not just the poems that are translated and the rest is in English, but that every piece of text has two versions. It’s very democratic, in a sense.

A: I really like that too. Tessa Ransford told me that in a way it was an absolute nightmare to produce, as everything had to be written and proofread in English as well as Arabic. Also, Arabic books are normally read in the opposite direction (back to front), so it’s interesting that although the languages are on equal footing, you are still imposing, in a sense, one format for the book.

J: That is a really good point, and one that is easy to forget as an English-speaking reader, that it’s not just the words you are blind to, but a whole structure of reading.

A: I’m trying to remember this myself, but how did you read the book?

J: I read it from cover to cover, I think.

A: Really? I read one poet at a time, maybe because at first I found myself identifying more with Tessa Ransford’s poems.

J: I have a question for you, what did you make of the fact that, after all, this is not a levelled, mutual translation?

A: Oh you mean because Tessa Ransford doesn’t read Arabic? I don’t know, and I thought it was so interesting! She writes so much about the book being a dialogue in the introduction, and it made me think of how this is much more common than we think. Poets meet up and translate each other’s work together, or poet and translator sit down and translate something. And I think I like that despite the fact that Tessa Ransford can’t speak Arabic, they still did this as a project and it didn’t become crippling. I do, on the other hand, find this ‘translation’, when you don’t speak the language you are translating from, a little bit odd.

J: Problematic, I would say. If anything, I would have wished for that to be more overtly acknowledged. It is wonderful that it is a dialogue and that that’s the intention, but the fact remains that one person does not speak the other’s language, and it would have been even more interesting if that had been reflected upon more, almost making it a part of the collection. I think that would be my main critique actually.

A: It’s funny, because it means that Hayatleh’s poems were translated twice, once by him into English, and then by Ransford working on the style. I know various projects where this is being done. In a way it’s almost sad because obviously not everyone speaks Syrian or Arabic, but you do have all these Syrian poets who do speak English and are willing to take part in the translation of their poems. Is that always going to be unequal?

J: The problem that it brings up for me is that this kind of process, to some extent, turns down the need for English speakers to learn other languages. This has always been the great thing about translators, that they are the people who know both; they are the vessels, as it were. This doesn’t happen here, and there is an element of that which I’m slightly uncomfortable with, because in practical terms, that means that there is one less reason for people to learn other languages than English. I do very much admire the effort behind it, though, and the ambition to create the work in spite of these linguistic obstacles.

A: A really lovely, albeit odd, thing would be if poets translating other poets in this way came into learning the language in the end.

J: You could argue that poets who translate others without knowing the language do it on the merit of being poets. That is their language and expertise, the poetical context of poetry in English which they bring to the table. It makes the skill of poetry itself valid, but it shouldn’t overshadow, I think, the linguistic skills of translating.

A: I think some of the poets I most admire are those who are both amazing poets and also translators. The German poet Jan Wagner, for example, has translated poets such as Simon Armitage and he says that the translation enriches his own poetry, because he is forced to think very carefully about why he chooses a particular image.

J: That would be the ideal case, wouldn’t it?

A: What were the differences between the two poets and cultures that you picked up on?

J: That is so difficult. One of the things I notednoticed was this idea of poetry versus prayer. Many of Hayatleh’s poems felt to me a lot more like prayer. Ransford’s poems, even though they deal with spiritual issues, felt more like what I am used to reading as poetry. I think it has to do with the form of address and the role of the ‘I’.

A: I interviewed John Burnside once and he said he loved reading poetry in Italian because they can talk about the soul and you can’t do that in poetry in English. Tessa writes in the introduction that she made some of Hayatleh’s poems less flowery. Maybe it is to do with that; in contemporary English poetry there isn’t the close link to matters of religion.

J: I guess it’s to do with how secular a society is at a particular point in time as well.

A: What I found with Hayatleh’s’s poems was that they were less defined by religion and more by his exile.

J: Absolutely! And I think that is where they find common ground, the works of both poems, in talking about what home means. It’s like a lowest common denominator. One of my favourite poems in the collection is the one about Pilgrimage by Tessa Ransford.

A: Do you think that it matters not knowing the references in Hayatleh’s poems?

J: I feel like if there is something that jars me and I need to look it up I will.

A: There is a community that will be able to read both, though, and have both sets of codes.

J: It reminds me of listening to the American author Junot Diaz talking about his novel The Brief Wondrous life of Oscar Wao at an event once. He was very conscious of how different the same book would be to different people. His grandmother from the Dominican Republic would completely relate to the Spanish words and the political history, whereas a twelve-year old science fiction geek would be entirely in the know when it came to those sections of the book. I love that.

A: With A Rug of a Thousand Colours, just like with Diaz’s book, you become aware of it, don’t you? That this is actually the case with most books. The effects of cultural codes are so intricate that one book will never be the same read for two readers.