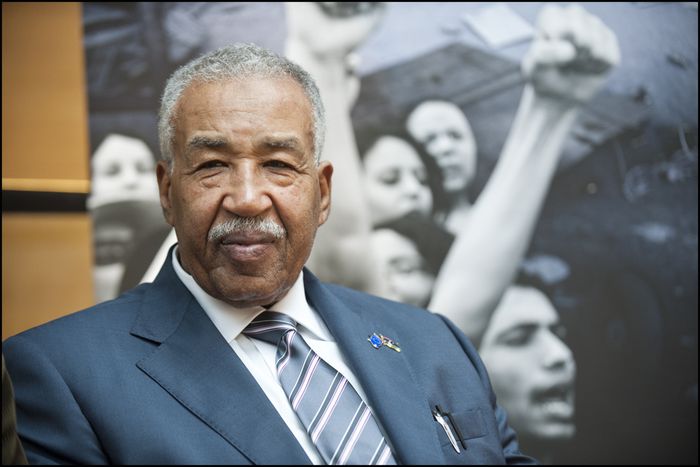

Activist Ahmed el-Senussi: Libyan prince and human rights hero

Published on

Currently a member of Libya's national transitional council, the prince was in solitary confinement during his imprisonment and did not speak to a single person for nine years. We meet in Strasbourg where the former prisoner of conscience was one of five Arabs to win the Sakharov freedom of thought prize for 2011

With the death of Vaclav Havel and Kim Jung-Il only a few days apart, it is as if vacancies have appeared on both ends of the spectrum of Good and Evil. What made the one man a great advocate of democracy and human rights and the other a deranged despot, historians and psychologists will have to decide. Curious to find candidates to follow in the footsteps of Havel, what better place to start looking than at the awards ceremony of the Sakharov prize for freedom of thought?

Prince and the pea

Named after the famous soviet dissident and human rights activist, this prize is an annual event since 1988 held by the European parliament to honour those who have fought for human rights - and who have paid the price. Sometimes, such as in the case of Mohammed Bouazizi, it is the ultimate price. Bouazizi, one the Sakharov laureates this year, died after setting himself on fire in protest against the regime of Ben Ali in Tunisia. Where he arguably started the arab spring, others across the region carried on the torch.

Five of them were singled out for this year's Sakharov prize, including the Libyan prince Ahmed el-Senussi. One of the world's longest serving political prisoners, this softly spoken relative of Libya's first, last and only king is 77 and spent 31 years of his life in Colonel Gaddafi's prison with a death sentence constantly hanging over him. Now he has to sit through forty individual interviews in a day, attend a press conference and deliver a speech to the members of parliament, all of whom give him a standing ovation. That is, with the exception of the members from the Dutch right-wing party for freedom headed by Geert Wilders. The prince is muslim after all. It will lead to a small scandal on twitter and in the Dutch press, but el-Senussi just shrugs it off with a resigned dignity.

Libya 2012

'I want reconciliation in Libya,' says the prince, hands folded neatly in his lap. 'Those in Libya who committed serious crimes should have a fair trial, but only those. The people overthrew the dictator with help from Europe, but there was no war between the people, no civil war. Just a fight against the regime. Libya is one big family.' Prince el-Senussi points to women and young people as two of the main driving forces behind the uprising. Although they had much to lose, they fought the good fight and made huge sacrifices. According to the prince, this should translate into increased political rights for women under the new regime. 'Young people too made huge sacrifices - and not just during the arab spring, which was on all the televisions. When I was in prison, 1, 200 young educated people were executed in one day in the same prison. We heard them screaming, but the media never reported it, no one in the west ever heard about it.' Still, the prince is happy with the role that the western media – both new and old - played in the recent struggle in Libya. Young people should be guaranteed free access to social media such as facebook and twitter, which the prince considers 'part of democracy'.

'When I was in prison, 1, 200 young educated people were executed in one day in the same prison'

Modestly, the grateful prince points to his Sakharov award as being a symbol of the end of Libya's isolation, rather than being his personal award. Still, he acknowledges that the people of Libya are happy that it has been awarded to him. He cites Nelson Mandela a role model; like him, prince el-Senussi found strength in prison. 'We did not lose hope. I did not abandon my human dignity. We always thought our dreams would come true, whether we would see that day ourselves or not. Now, freedom has finally been achieved. If I could remain optimistic in prison, I can certainly be so now.' That goes for the future of Libya as well as for his personal life; he learned that his wife had died while he was in prison. The prince is now actively representing the rights of political prisoners in Libya's transitional government. He has just one message for Europe and his grey moustache twitches as he delivers it: 'We are not terrorists, just because we are muslims. Do not treat us as such.' As Havel before him knew, with freedom come responsibilities. Time for the next interview.

Image: (cc) European Parliament