A people of many identities

Published on

Translation by:

paul mcintyre

paul mcintyre

The transmission of culture within Romany populations is very much an oral tradition, something which causes great difficulty in defining such a multi-faceted identity

The lack of authentic documentation on the Roma makes one tend to rely on the often vague information relayed by the media, which tends to neglect the many nuances which characterise these millions of people scattered throughout Europe and Asia. Despite this, there is nothing more interesting than exploring the hidden depths of their cultures and arts.or Often dismissed as ‘chicken thieves’ or quite simply ‘thieves’, the Roma have endured a tainted reputation since their earliest peregrinations. Their very name, moreover, appears to cause confusion for the Gajo, the non-Roma. This term is derived from the name of King Mahmud Ghazni who drove the Roma from India during the 11th Century, thereby becoming the enemy. But what is the difference between the Roma and Gypsies, Tsiganes, Bohemians, Manouches …

The lack of authentic documentation on the Roma makes one tend to rely on the often vague information relayed by the media, which tends to neglect the many nuances which characterise these millions of people scattered throughout Europe and Asia. Despite this, there is nothing more interesting than exploring the hidden depths of their cultures and arts.or Often dismissed as ‘chicken thieves’ or quite simply ‘thieves’, the Roma have endured a tainted reputation since their earliest peregrinations. Their very name, moreover, appears to cause confusion for the Gajo, the non-Roma. This term is derived from the name of King Mahmud Ghazni who drove the Roma from India during the 11th Century, thereby becoming the enemy. But what is the difference between the Roma and Gypsies, Tsiganes, Bohemians, Manouches …

According to Valeriu Nicolae, director of the European Roma Information Office (ERIO), founded two years ago in Brussels, there are no clearly established divisions. He describes himself simply as Roma. “We recognise each other clearly amongst ourselves, and it is sufficient to say only one word in Romany to know whether or not we belong to the same culture.” It is, however, the word “Egypt” which has for so long provided the root of the name for the Roma of several European countries, “Gypsy” in English and “Gitan” in French for instance. It is indeed towards Egypt that another part of the original population migrated, hence the confusion among Europeans as to their name. Social exclusion has also been a defining feature of the everyday Roma life since their earliest days: The French term “Tsigane”, the Italian “Zingaro” and the German “Zigeuner” all refer to the ancient Greek word “Atsinganos”, meaning “pariah”. The word “Bohemian”, on the other hand, has a less obvious meaning. This was originally used to describe someone who was furnished with a letter of recommendation from the Kings of Bohemia. Meanwhile, “Manouche” refers to the ethnic group the Sinti, the Roma of Piémont. Today though, the preferred term is simply “Roma”, signifying “man” in Romany, a language close to Sanskrit.

Culture and traditions

Are there, however, as many cultural differences as there are names? Valeriu Nicolae explains: “We share a common base of words which we use to indicate food, travel, time, fire…Other words have been adapted to different regions, to their societies and their politics. The same is true of our traditions. Certain Roma in Romania have adopted traditions which are different to those of Roma in France, for instance. People evolve according to where they live, as is the case for all people everywhere!” Hundreds of poetic traditions evolve and are perpetuated from one generation to another and it is their non-Christian side more than anything else which has been criticized over the centuries.

Centuries of adversity

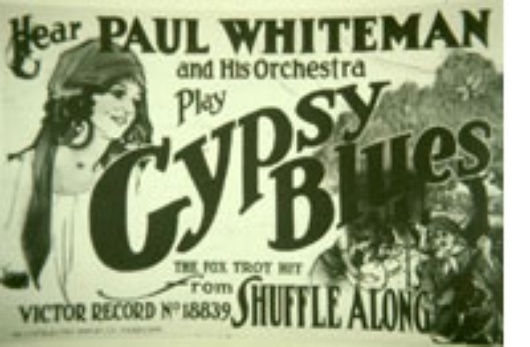

If for a long time their culture has appeared a closed one in the eyes of the critics, the Roma are actually masters of various forms of expression which today lend them a rather positive image in certain domains. Their music is without doubt their most lauded art thanks to – amongst others – the virtuoso violinist Rinaldo Olah, who merges comedy and tragedy in the feverish and bewitching notes which emanate from his golden fingers. Again, let’s cite the Gipsy Kings, this charismatic group who have without doubt aroused widespread interest in Roma music. Equally, other art forms are beginning to attract interest: theatre, photography and the circus are all becoming not only the means of expression of a collective identity but also efficiently substantiate and promote their cause. Gypsy’, a young Czech rapper of Roma origins declared at the release of his third album, “I use Tsigane instruments and don’t forget my musical roots – I simply turn it towards the future.”

Different directors draw inspiration for their films from this ill-treated minority, attempting – depending on the script – to produce them in either realistic or fanciful manners. Emir Kusturica dreams up romanticised, absurd lives, inviting the public to open themselves up to a different view. For Nicolae, “Kusturica films unusual, colourful Roma characters who become embroiled in the most extravagant adventures. Although we are not like that, it is normal to embellish reality in order to make a pleasing film. This is part of the beauty of cinema.” With his film Le Temps des Gitans, for example, Kusturica depicts the daily life of the Roma, played in Romany by Roma actors. Its release provoked some strong reactions, with the Roma declaring themselves satisfied to see a film “of their own” enjoying success, notably at the Cannes Film Festival.

In Swing, Tony Gatlif recounts the story of now sedentary Tsiganes. What particularly strikes the viewer is the “anthropometric identity card”. Introduced in 1912, these booklets which included both a photo and fingerprints of the carrier, served the Tsiganes as passports. Furnished with this document, they were obliged to present themselves to the relevant council authorities to mark every journey. This practice was only abolished in 1969. “It’s very important for people to recognise that these documents were issued by the French government and constituted a form of repression. This marked the beginning of the Manouche Holocaust. There is no need for castigation but it is very important for people to know, just for the record”, comments Nicolae before adding that “at a time when each of us is losing his traditions, the Manouches are suffering the same lot. Their children don’t speak Sinti (Romany mixed with Alsacien). They have absolutely no knowledge of their past. Some are ignorant even of the Nazi Holocaust. On top of this they are losing their musical heritage.” Even today the music of the Roma still enchants. Their concerts and festivals are multiplying, from France to Norway…Cultural events are scheduled almost everywhere: from festivals in homage of the jazzman Django Reinhardt to the Gypsy Swing of Angers or the Iagori International Festival of Gypsy music which has taken place in Oslo for the past six years. It appears that interest in Roma culture transcends all borders, wending its way along the road to what seems to be an incomplete multicultural European society, without the presence of an active ‘minority’ of over 12 million people.

Translated from Identitées bafouées