18, 648 ‘legal’, industrial deaths in Europe

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)'Produce, consume, die’: the soundtrack for European industrial casualties is provided by eighties Italian punk group CCPP. For the third consecutive year, accidents and serious injuries are up by one quarter and a fifth respectively. Overview spanning Poland and Italy via the UK and India

In a speech to the Counsel and Care charity in London in September, David Blunkett said that ‘people should work until they are incapacitated.’ The British former work and pensions secretary thinks this would keep the population in good shape. Work yourself into an early grave, he means - the topic is definitely fresh on the European agenda, as the polemic about having a 65-hour work week is ongoing.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there were 18, 648 ‘legal’ deaths in the European Union between 2003 and 2005, with almost 14 million accidents. If you count the annual deaths for every hundred thousand inhabitants, the most dangerous country to work in is Portugal (3.2), followed by the Baltic states and Malta (2.2 to 2.8). The figures vary between 1.8 and 1.9 in the Czech Republic, Spain and Romania, and countries in worse-off situations, such as Bulgaria, Ireland, Italy, Cyprus, Austria and Slovakia, which hit the European average of 1.5 – 1.6. On the lighter side, the United Kingdom (0.3) and Holland (0.4) are the safer countries to work in.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there were 18, 648 ‘legal’ deaths in the European Union between 2003 and 2005, with almost 14 million accidents. If you count the annual deaths for every hundred thousand inhabitants, the most dangerous country to work in is Portugal (3.2), followed by the Baltic states and Malta (2.2 to 2.8). The figures vary between 1.8 and 1.9 in the Czech Republic, Spain and Romania, and countries in worse-off situations, such as Bulgaria, Ireland, Italy, Cyprus, Austria and Slovakia, which hit the European average of 1.5 – 1.6. On the lighter side, the United Kingdom (0.3) and Holland (0.4) are the safer countries to work in.

Death by silence

These figures don’t mention the number of deaths which are impossible to define: for example, of illegal workers or immigrants whose bodies disappear, hidden by their pretender employers or recruitment intermediaries. It’s hard for family members and loved ones to notify local authorities of such disappearances, because of language problems, or not knowing exactly where the victims were working, or because of the struggle to get the authorities to respond accordingly and change old customs.

Around 100 Poles disappeared in the Apulia countryside in southeastern Italy

Around 100 Poles disappeared in the Apulia countryside in southeastern Italy, a famous tomato-cultivating region. Fourteen corpses were deported, but how they died remained a mystery. Letters from relatives which were sent to various institutions were never answered, at least until the Polish police decided to publish these on their own website in 2006. Italian writer Alessandro Leogrande even wrote an investigative book about it, Uomini e Caporali (‘Men and Corporals’, Mondadori, 2008).

The problem especially concerns Europe’s young women, who are ‘put on the streets,’ writes Paola Zanuttini in Il Venerdì di Repubblica (Friday at La Reppublica) weekly. ‘Guns and drugs soon follow the deaths, it’s a mafia triptych.’ The WHO figures also don’t include deaths caused by professional illnesses, which according to the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (ESHO), count up to around one hundred and forty thousand deaths annually.

Forgotten catastrophes

The WHO identifies two main sectors where deaths most often occur: in construction (30%) and in industry (20%). The former is characterised by the growing number of illegal workers without contractual rights, victims of the caporalato phenomenon (a system which takes advantage of immigrant workers in the agricultural sector in southern Italy). In the the latter, industrial accidents arise from the numerous fires, explosions and chemical diffusions, which often have a widespread impact on the atmosphere and the health of people in the surrounding areas.

The WHO identifies two main sectors where deaths most often occur: in construction (30%) and in industry (20%). The former is characterised by the growing number of illegal workers without contractual rights, victims of the caporalato phenomenon (a system which takes advantage of immigrant workers in the agricultural sector in southern Italy). In the the latter, industrial accidents arise from the numerous fires, explosions and chemical diffusions, which often have a widespread impact on the atmosphere and the health of people in the surrounding areas.

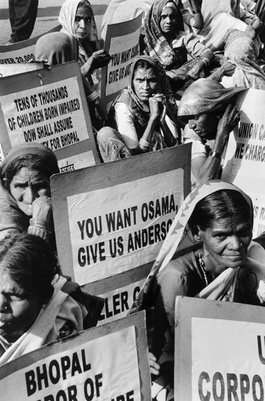

Just look at the twenty-eight who died at the Nypro chemical plant in Flixborough (near Scunthorpe), England in 1974, or the 23 who died at the Enschede fireworks disaster (Vuurwerkramp), a firework storehouse in Holland, after an arson attack in 2000. Unfortunately, the resonance of these tragedies rarely cross national borders to strike the European collective conscience. What about the horrors taking place outside of the EU? The Bhopal industrial disaster in India killed more than 3, 000 in 1984 because of a pesticidinal plant. More recently, explosions at the Gerdec army depot in Albania on 15 March 2008 killed 23. In both cases the plants were not in operation. In both cases, American multinationals were involved, including the Union Carbide Corporation (taken over by Dow Chimical) and the Southern Ammunition Company.

European media, wake up

In Poland, deadly accidents are considered to be ‘normal,’ sums up Anna from Krakow. ‘We don’t talk about that much,’ she says. The Halemba mining disaster killed 23 in the colliery in the town of Ruda Slaska, a southern industrial province of Silesia, but it didn’t seem to touch the public opinion. And even if the number of related disasters is dropping in Spain in general, they still continue to take place in the construction and transport sectors. Italy was relatively safe until a fire killed seven at the ThyssenKrupp steel mill in Turin in December 2007. ‘White deaths’ were back in the public eye: books, films, television reports and articles formed part of the outcry.

There was a similar reaction in Toulouse, southern France in 2001, when the AZF fertiliser plant belonging to Grande Paroisse (a Total affiliate), left twenty-nine dead. False allegations by the then-prime minister Yves Cochet and dailies Le Figaro and Le Parisien – especially in the wake of 9/11 - that this was linked to a terrorist act diverted the subject of hazardous industrial processes. The Grande Paroisse and former director Serge Biechlin are still awaiting trial. It should have begun on 29 September before the correctional tribunal in Toulouse, but it has been delayed to 29 February 2009.

Translated from L’Europa delle morti sul lavoro