The young artist lending her paintbrush to Yazidi women

Published on

She may look fragile, but Hannah Rose Thomas is resilient, just like the women she paints with. The young English artist has been selling her paintings since the age of 18, spending the money to travel and do a humanitarian work in Mozambique, Sudan, Jordan and Iraq. In 2017, she completed an art project with Yazidi women in Kurdistan, giving them paintbrushes as a tool to share their testimonies.

In her speech at the Trust Conference in London last year, Hannah Rose Thomas had to be given a hand-held microphone. Her clip microphone, delicately attached to her black jumpsuit strap, wasn’t powerful enough to capture her gentle voice. It’s no surprise, though, given that the 24-year-old British artist has been the voice of the voiceless since she was a teenager.

Hannah’s work has taught her to look for “the beauty, dignity and resilience of the human spirit, even in places full of pain and darkness.” When she heard reports in the media of thousands of Yazidi women and children being held in captivity by ISIS, she decided to take action. In the summer of 2017, Hannah travelled to Kurdistan with her paintbrush in hand to carry out an art project.

Art as a tool for advocacy

By then, the young artist already had experience in humanitarian work. In 2014, she travelled to Jordan as part of her studies and organized art projects with Syrian refugees in collaboration with the UNHCR. She painted tents with them, which were later exhibited in Amman on World Refugee Day. During her final year studying history and Arabic at Durham University in London, Hannah’s work went on display. In 2016, Hannah went back to Jordan to work on an art project for the Relief International organisation, where she spent time with children in two separate refugee camps. Her belief that art can be a powerful tool for advocacy has allowed her to work with refugees since the age of 18.

When she took off last year with psychotherapist Sarah Whittaker-Howe, Hannah wasn’t expecting to walk into “one of the most heart-rendering experiences” she has ever faced. During her time there, the young artist both painted Yazidi women and taught them how to paint their own portraits. In doing so, Hannah gave them the tools they needed to share their testimonies and heal their mental wounds, hopefully allowing them to overcome part of the trauma they faced during their time in captivity.

The Yazidis are a Kurdish religious minority in northern Iraq. In 2014, the territory they inhabit – the Nineveh province – fell in the hands of the Islamic State (ISIS). Tens of thousands of Yazidis were forced to flee, and while there are still thousands held in captivity today, Hannah met the women who managed to escape. Sarah, the psychotherapist, was there to support Hannah in her art therapy project. Needless to say, traumas are not easy to heal and art therapy can go a long way if proper psychological help accompanies it. “[Western media] constantly speaks of and presents [Yazidi women] through a lens of violence and victimisation. However, this is not the story the women want to tell in their paintings,” says Hannah, referring to the miraculous strength that she found in these women whose lives had been ruined.

A new life

The project itself took place at the Jinda Centre (Jinda is Kurdish for “new life”, ed.), a rehabilitation facility in Dohuk, Kurdistan. “The aim was to teach Yazidi women to paint their self portraits as a means to share their stories with the rest of the world. For two weeks, I taught the women how to draw and paint, and Sarah recorded their testimonies,” Hannah explains. Many of these women have never had an education, learned to read or write, or even held a pencil. This is why, for the women, Hannah believes that: “Testimony is an important part of the recovery process.”

Through their paintings, Hannah got to learn the women’s stories. Participation in the project was entirely voluntary, but those who took part told Hannah that painting was a helpful distraction from their memories, grief and their daily struggle to survive.

Liza was the eldest of the group. She has four children, two sons and two daughters, who are all – except for the youngest – being held in captivity by ISIS. Their father died during the 2014 invasion. Liza’s story is just one of many heart-wrenching accounts of the suffering Yazidi women and children face.

But from what she experienced during her time in Kurdistan, Hannah noticed that ISIS did not succeed in breaking these women. Art therapy was a way in which these women could re-assert themselves.

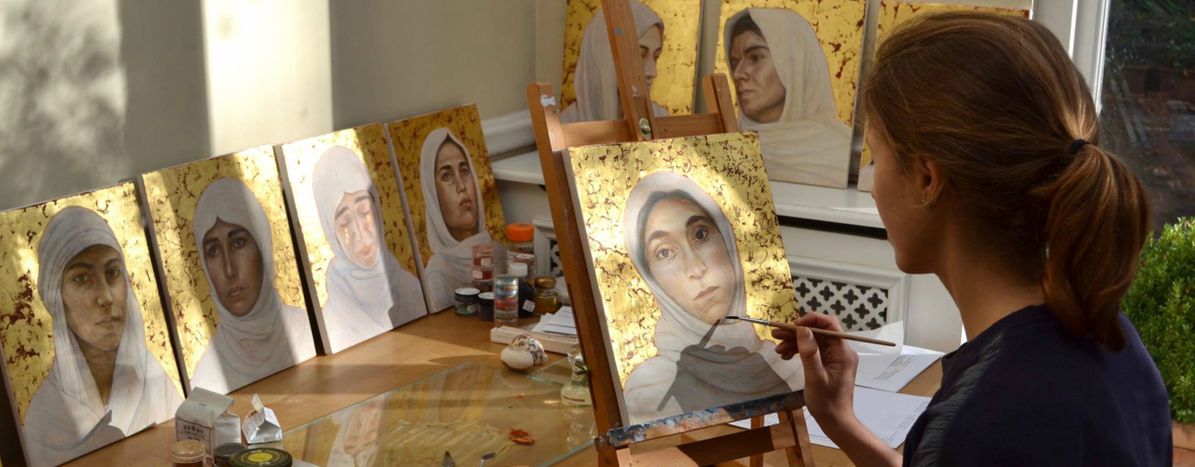

The paintings show colourful portraits of women with hijabs and eyes opened wide. One painting depicts a woman with tears in her eyes. This is the way in which the Yazidi women chose to portray themselves, touching the surface of their trauma and showing the world what they have been through.

“We must keep our hearts open”

Hannah says she will never forget the women with whom she spent time on a daily basis. “Following my return from Kurdistan, I began painting portraits of each of the women using gold leaf. Tears often fall while I paint and think about their stories; all of the loved ones who are still in the hands of ISIS and who they have lost. I hope to be able to use this exhibition as a way to advocate on their behalf,” she explains.

Hannah is the kind of artist who chooses to see the glass half full. Despite all of the cruelty, pain and conflict these women have seen, Hannah believes that – as a human race – we have more in common that what divides us. “We must keep our hearts open,” she concludes.

The self-portraits were first exhibited during the Trust Conference in London last year, but they have managed to make their way to the House of Parliament beginning on March 8th 2018 for International Women’s Day and will go on to be exhibited at the UN.

Holding the microphone close to her lips, Hannah concludes her speech at the Trust Conference by passing on one important message: “[The Yazidi women] wanted their stories to be heard, and they didn’t feel as though they were being heard by the rest of the world.” For her next project, Hannah hopes to be able to paint portraits of Rohingya refugees to raise funds in support of the humanitarian work that is being done in Bangladesh. Once again, she will be lending her gentle voice to those in need.