Orhan Pamuk's Museum of Innocence

Published on

The Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk selected exactly this scarlet house, dating back from the 19th century, for his museum. We explore this beautiful building, located in the midst of overflowing antique shops street in the Istanbul quarter of Çukurcuma (cats above and gulls below, this is the default symmetry of the Turkish capital):

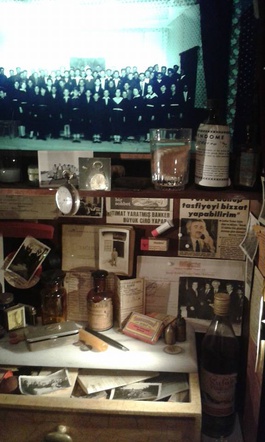

One of the first impressive things in The Museum of Innocence created by Pamuk and based on his eponymous novel, is the huge clock with a pendulum hanging between two of the three floors of the building. This temporal sword of Damocles, however, is overcome by a variety of subjects, all of which tell a story, as fictional as it is real. The collection includes over a thousand objects.

The institution was created by Pamuk, paid for with the Nobel Prize money for his novel "Snow." They say that the idea for the project came to Pamuk in the 80s, after a dinner between the writer with the last Prince of the Ottoman dynasty (who ended up in exile after the proclamation of the Turkish Republic). Reportedly, during his exile, the Prince was a Director of a Museum, and at the time of the dinner he was wondering what he could work on in Istanbul. Someone joked that he could take up a guide position at the Royal Palace museum. This brief remark may have inspired Pamuk’s idea for a man who is a guide of his own life and destiny, invisibly leading visitors through a house once inhabited by him. Several Turkish students are smoking cigarettes outside the building, before entering in the museum for some homework inspiration (Pamuk has not entered into the Turkish literary canon yet, but his books are slowly percolating through to extra-curricular classes).

The institution was created by Pamuk, paid for with the Nobel Prize money for his novel "Snow." They say that the idea for the project came to Pamuk in the 80s, after a dinner between the writer with the last Prince of the Ottoman dynasty (who ended up in exile after the proclamation of the Turkish Republic). Reportedly, during his exile, the Prince was a Director of a Museum, and at the time of the dinner he was wondering what he could work on in Istanbul. Someone joked that he could take up a guide position at the Royal Palace museum. This brief remark may have inspired Pamuk’s idea for a man who is a guide of his own life and destiny, invisibly leading visitors through a house once inhabited by him. Several Turkish students are smoking cigarettes outside the building, before entering in the museum for some homework inspiration (Pamuk has not entered into the Turkish literary canon yet, but his books are slowly percolating through to extra-curricular classes).

The students, all around 15 years-old, laugh awkwardly when it comes to Pamuk. They say he is not so easily accepted among the elders in Turkey because of his liberal views.

In the past, the 62-year-old writer has been sued by five Turkish citizens for insulting the Turkish state after making a statement in the Swiss media regarding the sensitive issue of the massacre of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, which many have labeled as genocide. Acquittal in 2006 followed, but the appellate court soon returned the case for retrial and Pamuk was fined 6,000 liras. A heavily discussed public figure, Pamuk reflects modern Turkey, although its kaleidoscopic nature can barely be accommodated even in his novels and this museum.

Recent public events are not without significance. After protests at Taksim Square, the civic atmosphere weighs heavy. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has spoken about the role of women, while there is even a debate for potential separate usage of the public transport by men and women. Such issues are indirectly or directly noted in Pamuk’s oeuvre. The modern Turkish women in his novels pay a price for their ‘free behaviour’ in a relationship before marriage or without it. “The Museum of Innocence” is one of Pamuk’s finest works. The writer has spent most of his life in a chair, writing (image born of his own self-reflection), inventing also his own manifesto on what the future of museums should be. The power of any individual destiny, which deserves to enter in a museum, is the basis of this concept.

Recent public events are not without significance. After protests at Taksim Square, the civic atmosphere weighs heavy. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has spoken about the role of women, while there is even a debate for potential separate usage of the public transport by men and women. Such issues are indirectly or directly noted in Pamuk’s oeuvre. The modern Turkish women in his novels pay a price for their ‘free behaviour’ in a relationship before marriage or without it. “The Museum of Innocence” is one of Pamuk’s finest works. The writer has spent most of his life in a chair, writing (image born of his own self-reflection), inventing also his own manifesto on what the future of museums should be. The power of any individual destiny, which deserves to enter in a museum, is the basis of this concept.

Four of the museum’s five floors consist of multiple displays, named after the individual chapters of the book. According to Pamuk, one does not necessarily need to read the novel for the museum to be understood. The museum tells us a lot about Istanbul, and especially the 30-year period from the 1970s to 2000. The museum collection is also full of photos revealing the life of the Turkish elite, shown in the novel by its protagonist Kemal, a wealthy businessman. Füsun, Kemal’s distant cousin and beloved, stems from the middle class.

In the museum’s halls, all the signs of everyday Istanbul life can be seen - utensils, pearl earrings, lipstick (stolen by Kemal from the bathroom of the already married Füsun), a scarlet dress – many objects reminiscent of Kemal’s love. With them, Pamuk aims to show that the stories of individuals can be more exciting than the representation of national history – and no less important. "Please reflect on my dilemma," reads one of Kemal’s omnipresent messages. "This is a more honest museum," said Katherina, a Greek student in anthropology who speaks in a self-restrained manner, stressing that the museum’s collections are essentially inexhaustible when it comes to analysis. "All museums aim to tell a particular story, often invented, and while this museum recognises a fictional narrative and in the same time it remains very real," adds Katherina.

In the museum’s halls, all the signs of everyday Istanbul life can be seen - utensils, pearl earrings, lipstick (stolen by Kemal from the bathroom of the already married Füsun), a scarlet dress – many objects reminiscent of Kemal’s love. With them, Pamuk aims to show that the stories of individuals can be more exciting than the representation of national history – and no less important. "Please reflect on my dilemma," reads one of Kemal’s omnipresent messages. "This is a more honest museum," said Katherina, a Greek student in anthropology who speaks in a self-restrained manner, stressing that the museum’s collections are essentially inexhaustible when it comes to analysis. "All museums aim to tell a particular story, often invented, and while this museum recognises a fictional narrative and in the same time it remains very real," adds Katherina.

She also points out that the museum shows how subjective one’s happiness or sadness can be, noting a caption inscribed on the top floor to recreate a room inhabited by Kemal: "I want everyone to know that I have lived a happy life."