Turkishness, minorities and women - Istanbul's nationalist taboos

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)The concept of ‘defending Turkishness’ allowed the atrocities committed on the country’s tiny Armenian population and repression of its other main community, the Kurds, to be minimised as the years went by. Artists, writers, directors and students are going against the tide of nationalism and the silence imposed on ethnic minorities

‘The Armenian genocide really means a lot to me,’ says Tayfun Serttas of the mass killings of Ottoman Armenians in 1915. We are sipping a cup of Turkish tea in a quiet coffee shop in Beyoglu, a district of Istanbul located on the European side of the city. Tayfun has spent thirty years as a Turkish writer and artist, and often includes the theme of minorities and cultural heredity which have been left in his country as a leitmotif of his work. The audacity with which he speaks is of a jarring candour; don’t forget, that we are in Turkey. It’s a country where being pulled up to stand in front of a tribunal for having ‘insulted Turkishness’ could be a very high probability for any one of its citizens.

The Turkish law has often caused revolts. 'Insulting Turkishness' is a crime enshrined in article 301 of the penal code. For years it has punished anyone who has openly questioned the issue of minorities or the government of prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in this country. Even though article 301 goes against article 10 of the European convention of human rights (which protects the freedom of expression – ed), and even though it was officially modified in 2008 (the word ‘Turkishness’ was replaced with the term ‘the Turkish nation’), the text is still in vigour. Just look at how writers, journalists, students, citizens and other personalities like nobel prize winner Orhan Pamuk have been treated.

‘Even the concept of archives is taboo for the authorities in my country’

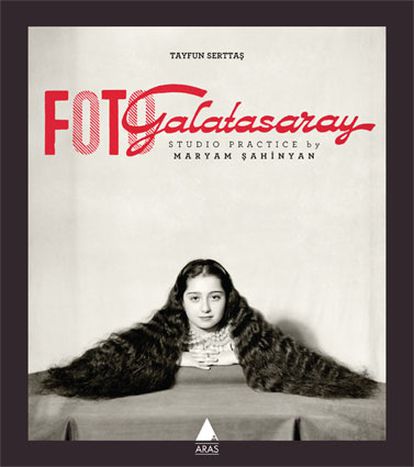

Nevertheless, Tafun lives for the thrill of the chase and the truth. ‘I wanted to know which artists came from the country’s ethnic minorities. We don’t know anything about them, there’s not a trace of their existence in any encyclopedias or museums,’ he adds, as we visit the editorial offices of Aras Yayınclık. The Armenian publishing house is the last one in operation in Turkey, and has published the fruit of work from the last two years of research, plunging through the archives. One of the discoveries includes Foto Galatasaray, a marvellous collection of 1, 000 photos, some of Armenians, taken over a period of fifty years by the photographer Maryam Sahinyan. ‘Even the concept of archives is taboo for the authorities in my country,’ says Tayfun. ‘Putting your nose in these kinds of documents means shining a light on a history which they have tried to demystify and erase over the years. Having said that, newer generations are more conscious of this and open to dialogue. The cultural fire of the revolution has been lit, I am sure of it.’

A film to break the silence

Çiğdem Mater is less optimistic. The famous activist (‘I’m just a director,’ she clarifies) speaks bitterly as the mid-afternoon heat chokes the neighbourhood of Elmadag. ‘Nationalism will always be a stumbling block. And Turkey is a conservative country.’ Mater is an editor at an independent news site called Bianet, hosts a radio programme on women’s rights and has just over 20, 000 followers on twitter. Above all, Çiğdem Mater is a director and co-producer of Armenia Turkey cinema platform, a cinematographic production association where the seventh art is used to ‘say the things that we haven’t been able to say in years, and to help us meet one another’. Since cinema platform was founded in 2008, it has helped directors work on a mutual dialogue of reconciliation between the two communities.

‘It’s true that things are evolving. The newer generations are protesting in the streets. But the truth is that Taksim square is the only place in Istanbul where people come together. It's like Hyde Park, where everyone has the right to their little bit of ground,’ adds the director ironically. ‘There was a genuine mourning period after the death of Hrant Dink (the journalist and editor-in-chief of Agos, a weekly Armenian newspaper, was assassinated in 2007 by a nationalist Turk who disagreed with his articles about the Armenian genocide - ed). However, Çiğdem is remaining prudent. ‘That doesn’t mean that all of those thousands of people who took part in the funeral in 2007 are ready to recognise the Armenian genocide and Kurdish identity today. It just helped ease their conscience.’

Feminist review

Will Turkey one day be able to see pasts it historical myopia and encourage a broader intercultural dialogue? ‘That’s what we’re trying to do by explaining our stories and the difficulties that the women of this country have to face, no matter what community they come from. Domestic violence against women and the Kurdish question are crucial issues for our magazine,’ explains Ayca Gunadin, who is not yet 20 years old. Along with Burcu Tokat and Esra Aşan, she is a member of a group of female activists publishing a university newspaper called The Feminist Approach to Culture and Politics ('feminist yaklasimlar kultur ve siyasette'). The publication aims to breach the silence with which these themes have been shrouded in over the last decades.

‘Artists can adventure in areas which politicians don’t have access to,’ the writer Elif Shafak told me in March in London. Her name also hit the headlines after she offended the Turkish national identity for a single sentence which appeared in her sixth novel, The Bastard of Istanbul (2006). ‘Art and literature have the power to go beyond cultural and identity barrier. Art can create connections between human beings; it’s the identity which swirls around political speak which creates divisions.’

This article is part of the fifth edition of cafebabel.com’s flagship project of 2012, the sequel to ‘Orient Express Reporter II', sending Balkan journalists to EU cities and vice versa for a mutual pendulum of insight. A huge thanks to Burcu Baykurt and Cansu Ekmekcioglu

Images: main courtesy of © Aras Yayınclık/ Tayfun Serttas blog in-text: 'Neighbours' by Armenian filmmaker Gor Baghdasaryan, courtesy of © ATCP official facebook page; Burcu and Esra by © Maria Teresa Sette/ video (cc) SaltonlineIstanbul/ youtube

Translated from Turchia, sfida ai tabù nazionalisti