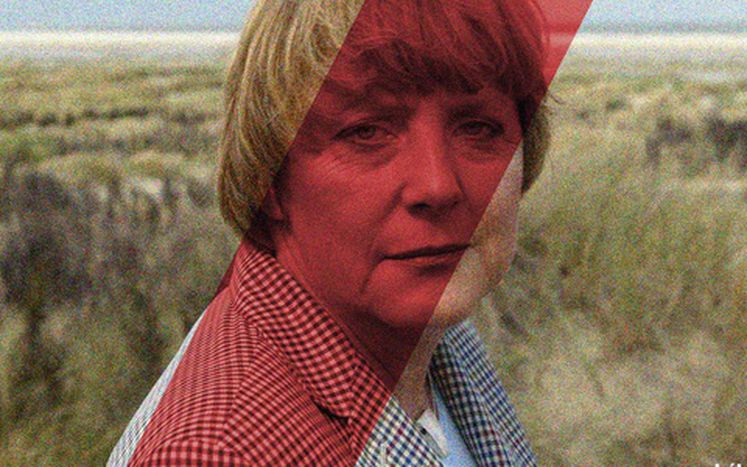

The aftermath of the German elections What next for Angela Merkel

Published on

Translation by:

Garen Gent-RandallWhen they went to the polls in September, Germans were not just electing a leader for their own country. They were electing someone who will play a significant role in the fate of Europe as a whole.

At least, that's what Ulrike Guérot, the director of the Berlin office of the European Council on Foreign Relations, has concluded. During the elections, she wrote an analysis entitled 'What Europe expects from Germany and what Germany will not do', which was viewed a surprising number of times (1.2m downloads - Ed.). During the parliamentary elections of 22 September 2013, the chancellor Angela Merkel and her CDU/CSU party (a conservative union - Ed.) emerged victorious with 41.5% of the votes. However, she will have to make concessions to her rivals, the SPD (Social Democratic Party - Ed.), in order to form a 'grand coalition' government.

Things are not what they seem

In Europe, Germany is widely perceived to have economic hegemony over the whole continent, a perception whose flames national newspapers are only too willing to fan. Everyone thinks that Europe's future depends first and foremost on Germany's political choices. But the key currently lies in knowing whether the SPD will be able to influence the foreign and economic policy that chancellor Angela Merkel has thus far pursued. Nothing could be less certain. If you were to believe Ulrike Guérot, Germany is constitutionally and socio-economically stagnant, and its position on Europe will remain largely unchanged. Why? First, the image of a Germany which imposes its leadership on others isn't a popular idea amongst Germans, for obvious historical reasons. That's why it 'doesn't see [or refuses to see] that Europe has been served to it on a silver platter.' Second, let's not forget that Germany remembers its indenture to the United States only too well, only regaining full sovereignty in 1989. This is why Germany's economic domination is not matched by a strong strategic military policy.

It's clear that the external perception of Germany's economic clout doesn't correspond with the reality on the ground. Of course, some people will point at the figures published by the consultancy firm McKinsey in July 2012. It shows that because of the asymmetry between national economies which operate under very different leaderships, the profits generated by the introduction of the euro are not at all evenly distributed. In all of the eurozone combined, economic activity generated €300bn in ten years: 50% in Germany, 25% in northern Italy (a major exporter) and 25% in other countries.

There is not only one Germany

But make no mistake. Ulrike Guérot recognises the fact that this disparity may be difficult to comprehend. Germany's economic success, although phenomenal on paper, does not necessarily reflect the reality on the ground.

The truth is that there is not just one Germany, but three. A poor East Germany. An old West Germany, which, like the Rhineland, was once prosperous, but whose infrastructure (notably transport) was weakened by the costs of reunification, eventually leading to progressive structural decay. Finally, there is South Germany, the rich exporter, the only Germany to have benefited from the profits generated by the euro.

Relying on Germany to help its neighbours through troubled economic times would be a tall order. Currently, Germany has neither the ambition nor the means to take on this paternalistic role. Even if the SPD understands the scale of the grievances of European states (as seems to be the case), particularly when talking about stopping social dumping, they have very little room for manoeuvre. The way Germany's economy and society works can't be changed that easily, and even less so in the case of a coalition formed by two opposing parties. The SPD has numerous policy aims which include a minimum wage of €8.50, the development of transport links, and a 'social Europe'. However, whether these aims can come to fruition in the grand coalition is another matter entirely.

Translated from Allemagne : après les élections, où en est-on ?