Solidarity: the end of a myth

Published on

Translation by:

lucy thomas

lucy thomas

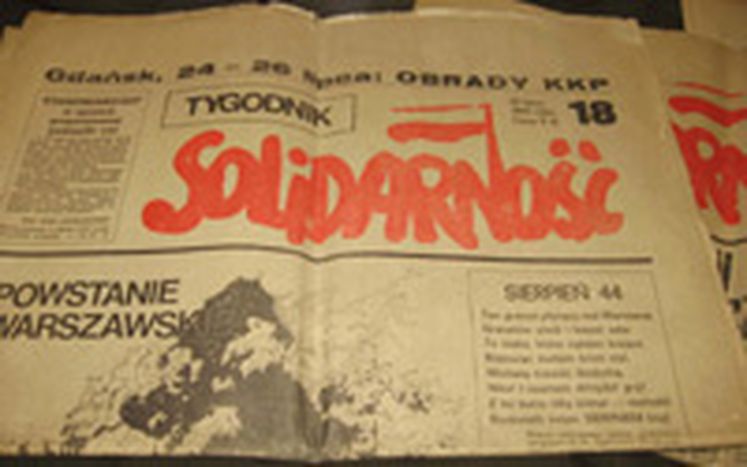

While the Polish trade union ‘Solidarity’ celebrates its 25th anniversary, what has become of Lech Walsea and his fellow freedom fighters?

Lech Walesa, Anna Walentynowicz, Andrzej Gwiazda, Karol Modzelewski, Zbigniew Bujak, Tadeusz Mazowiecki were the icons of ‘Solidarnosc’ (Solidarity), the first independent trade union of the ex-USSR, at the root of the general strikes at the work site at Gdansk in Poland, in August 1980. These names, well-known and respected by all, having contributed to the overthrow of the communist regime, launched the democratisation of the country and breathed the spirit of a brighter tomorrow into the heart of the Polish people.

Although their biographies are varied and their trajectories sometimes opposing, there is one thing all the founders of Solidarity have in common: the democracy for which they fought so unrelentingly does not seem to have brought what they had hoped.

After the 1990s, the members of the trade union followed different paths. Some have stayed active on the political scene and remain influential to a greater or lesser extent; others have completely retired from public life.

Politics, university or cinema?

The most famous personality, Lech Walesa, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1983, was the first Polish President elected at the free elections of 1990. Subsequently, his defeat in the presidential elections of 1995, then 2000, to post communist candidate Aleksander Kwasniewski showed that Lech Walesa - who had been an idol of Polish society at the start of the nineties - had lost the confidence of his compatriots, notably due to his moral conservatism and the important part played by the Catholic Church in political life.

Those who before were ready to “put their lives in his hands” would now rather that he sticks to his role as commentator on public life. Tadeusz Mazowiecki, one of Walsea’s principal advisers, co-author of Solidarity’s statutes - the first chief of a non-communist government- also lost the confidence and support of Polish citizens year after year. Having fallen out with Lech Walesa, his carrier developed in the international scope, when he became the UN’s special reporter on Human Rights in former-Yugoslavia. Today, he is honorary president of the centre-right party Union for Liberty (UW).

This draws parallels with the situation of Zbigniew Bujak. Former leader of Solidarnosc for the Mazowsze region (the centre of Poland including Warsaw) and hero of the clandestine resistance during the marshal law of the 1980s, he was deputy of the Polish parliament from 1989 to 1997.

After initially enjoying huge popularity, he won only 3% of votes in the Warsaw municipal elections in 2002. Today, Bujak, like Walsea, plays an observational role of national political unrest.

Karol Modzelewski, spokesperson for Solidarity, then senator at the time of the first democratic legislature, quickly withdrew from the public eye to pursue a university carrier, and has since taught history at the University of Warsaw.

Andrzej Gwiazda, co-founder of the union and former engineer on the work sites still criticizes Walesa, who, according to him, was allegedly a communist secret service agent. Imprisoned during the marshal rule, after 1989 Gwiazda was the leader of the alternative world order movement in Poland.

As for Anna Walenrynowicz, 76 years old, she is equally displeased with the former Solidarity leader. She was sacked on 7th August 1980 for illegal union activity, and set off worker strikes which led to the creation of the union. She is featuring in the news as she wants to bring to justice the German cinematographer Volker Schlöndorff, who is currently shooting a film in Poland about her life. She has accused him of “treating my biography in a vulgar way”.

The harder they fall

The actors behind Solidarity were allies in the 1980s, but it appears that apart from a few poignant examples, the protagonists are today divided, and oppose rather than support one another. For the first time, the duel at the last legislative and presidential elections did not take place between the right, as represented by the former and current militants of Solidarity, and the left, composed of the former members of the unified Polish workers party (PZPR). Instead, the true rivalry appeared between the coalitions and militants resulting from Solidarity.

The ex-allies angered each other and brought affairs to public attention which never should have been highlighted. It is understandable that on launching oneself into an election, each party or candidate has as objective to win; but is it fair game to do this by any mean?

Quarrels and resentment create a situation in which the young may feel inclined to think that their respect towards Solidarity is more based upon events seen in the history books rather than that which they see in reality today. The icons of Solidarity have ceased to be credible examples.

Translated from Co się stało z ikonami Solidarności?