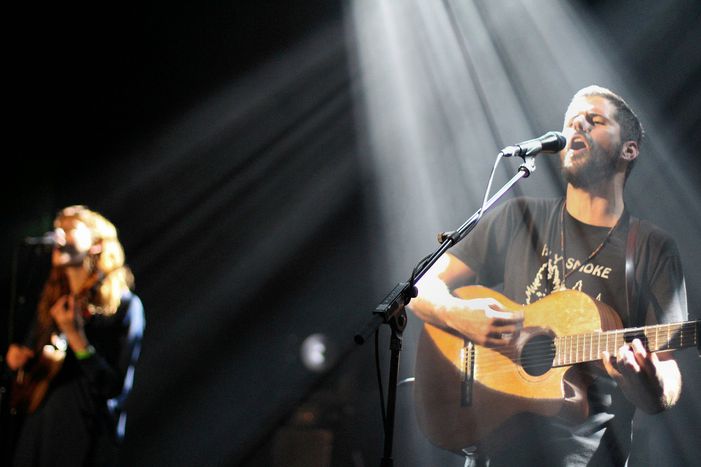

Nick Mulvey: "Without obstacles, without limitations"

Published on

British folk singer-songwriter Nick Mulvey has had a whirwind year. Since releasing his first solo studio album First Mind in May last year, he's picked up a Mercury Prize nomination, toured the world, and gotten married in Bhutan.

He tells us about leaving Portico Quartet, studying music in Cuba and not trusting David Cameron.

It’s been nearly one year you released First Mind. What have you done since then?

It has been an amazing year, and a very busy one. Touring almost all the time, supporting the album around Europe, America. The group of people I’ve been working with has enlarged, and it's become a family. My wife Isadora is playing with me as well. We got married in January - we took some time in Thailand and spontaneously decided to get married - then we got an invitation to go to Bhutan. It was very immediate. It was the first international music festival in Bhutan ever. They invited us to perform in the festival. And we had a very special traditional Bhutanese wedding ceremony.

The administrative aspect was in Thailand but the ceremony aspect was in Bhutan, very authentic. It was in the 15th century Buddhist monastery on the mountainside, near the capital, conducted by an abbot. The way of life and the practice of this monastery have been unchanged since medieval times. We sat in the middle, the two of us in traditional clothes as everybody was making a lot of offerings and symbolic gestures. My friend and my father were there too.

It was a big move to go solo. What exactly was the need you felt at that time?

It was really about living my truth and owning my creativity. So within Portico Quartet, I needed to make a change, I needed to grow, to try new things. On a very special level, I wanted to play the guitar, and I was playing the hang for a very long time. I wanted to sing, and wanted to do the lyrics as well as I didn’t make the key things in the band.

Did you get bored at some point?

It was time for a change in my life. I was getting a bit tired, but I was also getting a bit uncreative. As I remember, it was a very specific moment when I said to the guys that I was leaving the band. I was thinking for a while, maybe a few months, and then talking to very confident friends. Basically, it became very obvious that I was on a very different base, on a very different journey. And we were in a service station on the motorway in Southern Germany. They were talking about music and how to make the next album. And when you’re four people, sitting around a table talking about the new direction, the new concrete action, for me it was really obvious I felt like now I had to say something. I just said, “Guys, I don’t know if I’m gonna part of this.”

It was time for a change in my life. I was getting a bit tired, but I was also getting a bit uncreative. As I remember, it was a very specific moment when I said to the guys that I was leaving the band. I was thinking for a while, maybe a few months, and then talking to very confident friends. Basically, it became very obvious that I was on a very different base, on a very different journey. And we were in a service station on the motorway in Southern Germany. They were talking about music and how to make the next album. And when you’re four people, sitting around a table talking about the new direction, the new concrete action, for me it was really obvious I felt like now I had to say something. I just said, “Guys, I don’t know if I’m gonna part of this.”

There was a bit of shock and then a bit relief and a realisation, an immediate acceptance because we all knew in our heart that it was not really a decision, it was happening already. A natural flow. The truth.

You're creating music much more different from the jazz of Portico Quartet. What's your aim as a songwriter?

My aim as an artist is to really allow my expression to live, to be without obstacles, without limitations. As a writer, I’m always trying to think ‘musically’ and second, thematically. Afterwards. I’m always trying to communicate with your subconscious, to your right brain. And concepts, ideas, this stuff comes later. And then I see the words.

You said one time, “I want to warm the room”. What did you mean?

I want to communicate. I want to have a conversation, I don’t want to be hard to understand or difficult to interpreted. Mostly, songs like ‘Meet me there’ are very open.

At 18, you decided to study guitar and percussion in La Havane. How did you get in?

It was interesting and very typical of modern Cuba because a friend travelled there and spent one year in the school. He told me about it. When he came back, he told me "Nick you have to go there." When I said it’s typical, it’s because the school is half-Cuban, half-international. There are 2,000 people and for the Cubans it’s super competitive, for the international students, it’s a good level but because you’re paying, it’s easier. If you have some standards, and enough money, you can get in. But the level of the Cuban students was so high. They could play everything.

How did you deal with the society in Cuba? I felt a bit of shock. First, I tried to make sense of the country and after a while, I stopped and it was much better. I had my own experience of Cuban bureaucracy and everybody notices all the clichés like the taxis are old Cadillacs. But I had one interesting experience when I played my own songs with a young Cuban musician. He was interested in my songs and asked me “Oh, you play your own songs?” I replied, “Yeah, of course.” And then I realised that they never play their own songs. They all played in a Cuban style, in a traditional style and if they compose their own songs, they would compose it in the style of the Cuban music. But they found me crazy and it’s the main difference I experienced between us.

How did you deal with the society in Cuba? I felt a bit of shock. First, I tried to make sense of the country and after a while, I stopped and it was much better. I had my own experience of Cuban bureaucracy and everybody notices all the clichés like the taxis are old Cadillacs. But I had one interesting experience when I played my own songs with a young Cuban musician. He was interested in my songs and asked me “Oh, you play your own songs?” I replied, “Yeah, of course.” And then I realised that they never play their own songs. They all played in a Cuban style, in a traditional style and if they compose their own songs, they would compose it in the style of the Cuban music. But they found me crazy and it’s the main difference I experienced between us.

You seem to be very eager to discover new different cultures. Where does it come from?

A combination of things. First, our generation: we have the iPod shuffle. You listen to Radiohead and then Biggie Small and then Queen. It’s natural for our generation to listen everything and the whole of music history is available on your phone. And also, within my family, there were a lot of different styles, we had a very nice album in French called Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares, for example. But the main reason why I was interested in music was a reaction against the music of my country. I was interested in music if it was from a different decade or a different continent. When I was a teenager, I wasn’t interested in Arctic Monkeys, The Libertines. I was interested in music from Africa or Southern America. But in recent years, that changed and I’m listening to Arctic Monkeys now, the first album. In the last two years, I've been more into the music of my country.

You said your father had a big influence on you. What the best thing you learned from him?

He showed me the first chords on a guitar. He was playing every night to my brother and I before going to bed. So it’s the very early influence of music I had. And the music after normalised my life. He played the Beatles all the time or old American kinds of spiritual songs, sort of Gospel, Simon and Garfunkel. And then he brought a lot of ideas into the house: Buddhism and yoga especially, meditation and mindfulness. He got into that when I was in my teenage years.

The UK Prime Minister David Cameron once said he enjoyed cooking while listening to you. You reacted saying you were “a bit sick.” Why? What he said was kind of strange. Cause he said exactly: “I listened to Nick Mulvey while I’m cooking but it’s a bit grungy”. You could use any words but I think there is one word you can’t use to describe my music: it’s “grungy”. It’s really really, really not grungy. I actually think he had been advised by someone to say something cool. On a personal level, everybody is welcome to listen to my music of course. But, you know, I don’t trust David Cameron. I don’t trust any or many politicians, certainly not him. So it’s a strange compliment.

The UK Prime Minister David Cameron once said he enjoyed cooking while listening to you. You reacted saying you were “a bit sick.” Why? What he said was kind of strange. Cause he said exactly: “I listened to Nick Mulvey while I’m cooking but it’s a bit grungy”. You could use any words but I think there is one word you can’t use to describe my music: it’s “grungy”. It’s really really, really not grungy. I actually think he had been advised by someone to say something cool. On a personal level, everybody is welcome to listen to my music of course. But, you know, I don’t trust David Cameron. I don’t trust any or many politicians, certainly not him. So it’s a strange compliment.

The general elections are coming soon. Are you keeping a keen interest?

I’m really interested in the state of the world. But I don’t believe that the current system will fix itself. I believe that we need new systems. So voting is kind of strange isn’t it? Voting is like reproducing the same system. But also I do understand we are in this current system, so there could be something more interesting to do, like using your vote somewhere. I haven’t decided what to do at this stage because I maybe will vote cause I don’t want UKIP to be elected.

Generally, I’m not a fan of politics. I mean, I think it’s systemically corrupt so it doesn’t matter who takes over - and I think Obama is a good example of this – because the position is corrupted. And I tell you what - the politics becomes spiritual for me because most people find issues at the global scale overwhelming. And I think to myself, "Where can I have influence truly?" And then the question of global realities becomes much more down into here and now, to my own life and if it can change my own life. And change my own attitudes, my own developments. So the question of the political becomes more spiritual because it’s more about me confronting my own witnesses, my own greed, my own base appetite. I don’t believe I can really affect things beyond my own life.

Nick Mulvey - I Don't Want To Go Home, the latest single from his debut studio album, First Mind