Mental Blok: Talking to the Vlaams Belang.

Published on

By Rose Kelleher. Vlaams Belang’s views on Belgium and the European Union (1/2) What future for tiny Belgium? That depends on who you ask. A Brussels blow-in ignores warnings and talks to the controversial Vlaams Belang party. “I was once in a bar in Leuven, and I was drinking with some people. Someone recognised me and said “Don't talk to him! He's from Vlaams Belang.

” Out of five people, two of them shook my hand and said “Hey, nice to meet you I never met one”. Three others said “Don't speak to him, he is a devil” and they started telling their ideas about me. They think they know me. They don't know anything about me.”

Belgian politics are confusing at best. What foreigner is foolish enough to try to understand, let alone comment on, the seemingly self-destructive political disputes that are as familiar to Belgians as surrealist art or Red Devil defeats? Outsiders usually know little about the country's government, except that that there rarely is one. Few are familiar with the disputed BHV zone or the Flemish secessionist movement. But many have heard of the Vlaams Belang party. Cafebabel takes a deep breath and speaks to Belgium's pariah right-wingers.

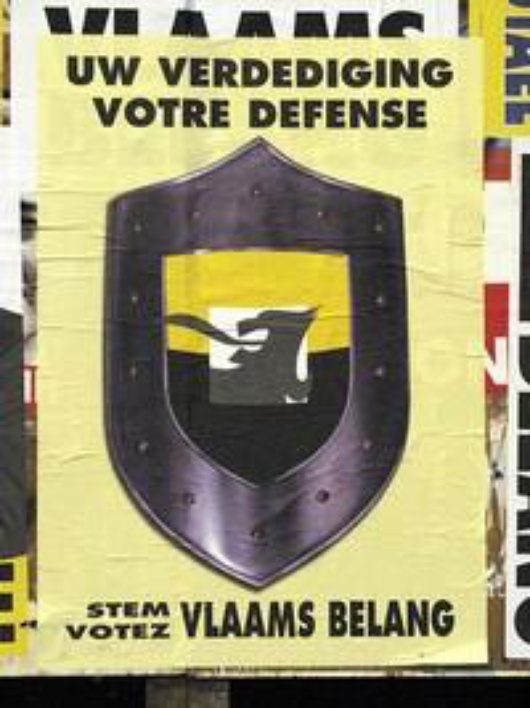

Housed in a looming office block on Place Madou, the Vlaams Belang national secretariat is inconspicuous except for signature yellow and black posters on the windows. It's 3.30pm on a Thursday and inside we find the brightly lit office immaculately clean but empty of staff. The room is overstuffed with leaflets and pamphlets in Flemish and French, and tables piled high with literature for sale. On the walls there are posters with “Republiek Vlanderen” and glass cabinets displaying party merchandise.

In an ideal world, Mr. Frédéric Erens, chairman of Vlaams Belang Brussels, would like to be seen as a member of a respected political party that promotes, among other things, better public transport in this city. After all, his party enjoys substantial support from the electorate. But not many people can get past the fact that he was once a member of the Belgian Front National. Or this party advocates for a white Europe. Or that there has been a cordon sanitaire on the party since the early eighties, which even a 2004 name change failed to remove. Or that “Franzen Ratten Buiten” (French Rats Out) is a sinister, if irrational slogan commonly heard among its supporters.

Can the Vlaams Belang be

separated from its extremist elements and its shady past? Have they, by virtue

of copping 15% of the votes among the Flemish electorate in 2010, earned the

right to be heard? Similar questions are asked in other European countries

(think Italy's Northern League, France's Front

National or the Netherlands'

Freedom Party). Should we

just ignore them and hope they go away? By talking about them, are we

legitimising, or worse, promoting extreme views? Last year in the UK, the

right-wing British National Party's

Nick Griffin was “legitimised” by a BBC invitation to appear on a “Question

Time” panel. It caused outrage as it was seen as an opportunity for him to use

the pulpit to air his dodgy views. Even Mr. Griffin himself told The Times newspaper that the BBC was “stupid” for allowing him on

the show.

them, are we

legitimising, or worse, promoting extreme views? Last year in the UK, the

right-wing British National Party's

Nick Griffin was “legitimised” by a BBC invitation to appear on a “Question

Time” panel. It caused outrage as it was seen as an opportunity for him to use

the pulpit to air his dodgy views. Even Mr. Griffin himself told The Times newspaper that the BBC was “stupid” for allowing him on

the show.

Mr. Erens says that journalists don't want to interview his party. He says “It is because the public have made up their minds about what Vlaams Belang is and what they stand for. For example, once a journalist wrote in a paper that we want women to stay at home, or that we have military camps. We are a caricature, people think we eat babies, lock children in the basement.” Mr Erens and colleague Mr. Wouter van den Meersch talk to cafebabel about Belgium, Europe, and the best place in Brussels for a coffee.

How would you describe the current political and social climate in Brussels? Frédéric Erens: “Brussels has many issues. The most important issue is that we have 19 different city councils, one regional council, 6 police zones, 19 social districts. It's too much, and they are not working together. They are often working against each other. Brussels used to be one of the richest regions about 20 yeas ago, now we are the poorest, with 20 to 22 % unemployment, and you see that number of people in school is falling.” And the austerity measures to tackle Belgium's national debt? FE: “Nobody speaks about Belgium's national debt, but it's one of the realities. You will never read about it in a Belgian paper. Why? Because it’s better to lie to people than to tell the truth. We have a debt of one hundred per cent. It's enormous, and the government is selling what they have in reserve, as well as a big part of real estate. It's really short term, it’s like they know the country will not exist in ten or fifteen years.”

Wouter van den Meersch: “From a practical point of view, I'd say these measures could be beneficial, hard medicine, perhaps. But I don't think of these kind of powers at the level of the European Commission. It's a bad idea to confer that kind of power to them.”

You resent supporting Wallonia economically. Why? FE: “Solidarity is not about government saying “give me your money, and I'll give you some back”. People feel more like they are robbed, and it's creating a system where the people on the receiving end feel bad. Everyone feels bad. It's really a problem of the Parti Socialiste. They want to keep the people poor so that they are eating out of the hand of the party. And they strike for everything. It's difficult to get people to invest in this atmosphere. And the unions are making money from unemployment. It is more interesting for them to have more unemployed people.”

If Wallonia was not poor,

would you still want a separate Flanders? FE: “Yes. And Wallonia

would be a very good neighbour. They would come and eat at my home, but we

don't have to stay married. Belgium is a country that was made in London."

If Wallonia was not poor,

would you still want a separate Flanders? FE: “Yes. And Wallonia

would be a very good neighbour. They would come and eat at my home, but we

don't have to stay married. Belgium is a country that was made in London."

And so Flanders is a country that you will make in Brussels? FE: "Brussels is a part of Flanders." What does the name “Belgium” mean to you? WvdM: “"Problem”. It's not a country, it's a political system.”

FE: “”Bad marriage”. I like Belgium, but it doesn't mean we have to stay together. Look at Czechoslovakia.”

Your party is quite skeptical of the power of the EU institutions? FE: “We are very eurosceptic, about the system and about the European Commission. The Europe that they are constructing now is not good. They want to make a Europe where twenty people are deciding for all the other countries and we do not agree.”

What do you like about Brussels? FE: “I like the Chatelain. I have a small child now, almost three years old so I spend time with pampers and giving baths and I don't really go out much. I like the market there on a Wednesday night."

WvdM: Place St Katherine. I have very nice memories from there. Inside the Brussels Central station also, it used to have a very nice atmosphere. But that was in the past. It has changed a lot. ”