Juggling Origins on Wine and Crackers

Published on

French or German? Parisian or Berliner? It doesn't necessarily take a mixed background to have no ready answer to the origin question. But why does a mosaic life line have to be a source of confusion? How my personal quest for identity became a source of wonder and pride.

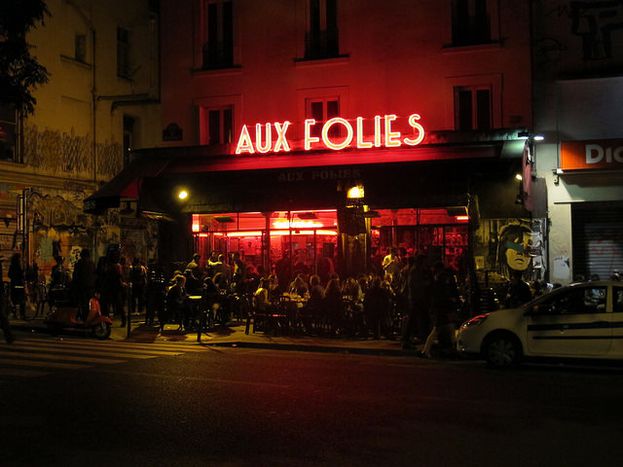

Amid the hustle and bustle of an early evening get-together, young people in artistic outfits are exchanging greetings, business cards and la bise, chatting happily away over wine and crackers on the capital curb. In this kind of situation, the question I love and dread most usually hits me fairly early on. "Where are you from?" What could be absurdly easy often transforms into an intermittent Q&A session in the course of which I will earn the badge of either "the French girl who isn't really French," "the world-savvy European who talks about India a lot" or "the German who confuses everyone because she seems so French." While this cross-cultural riddle-solving can be interesting, sometimes even hilarious over wine and crackers, it is more than a casual guessing game.

How many homes for one identity?

Wherever you are born, you will be graced, among other things, with a mother tongue, fond childhood memories of TV programmes, certain culinary preferences, a specific school education and different social quirks. It is as much about the Sendung mit der Maus, as about Bordeaux and your sense of humour – or the entire lack of it. But what happens once you leave home to live abroad, studying at various universities, adding to your language repertoire or falling in love with someone from another country? "Well, that one is a little bit difficult." Tim Mac an Airchinnigh, who was born in Dublin and is now studying for a PhD at a Parisian university, gives another stir to the sugar lump he had just dropped into his espresso when I asked for his thoughts on the concepts of origin, belonging and "feeling European."

Wherever you are born, you will be graced, among other things, with a mother tongue, fond childhood memories of TV programmes, certain culinary preferences, a specific school education and different social quirks. It is as much about the Sendung mit der Maus, as about Bordeaux and your sense of humour – or the entire lack of it. But what happens once you leave home to live abroad, studying at various universities, adding to your language repertoire or falling in love with someone from another country? "Well, that one is a little bit difficult." Tim Mac an Airchinnigh, who was born in Dublin and is now studying for a PhD at a Parisian university, gives another stir to the sugar lump he had just dropped into his espresso when I asked for his thoughts on the concepts of origin, belonging and "feeling European."

After prolonged stints in London, Switzerland and Australia, he feels a bit at odds between France and Ireland: "I think a lot of emigrants will identify with the feeling that we pay return visits to an increasingly foreign country. We lose touch with how the new buses work, who the local celebrities are, the changing price of drinks or groceries." Tim still returns to Dublin fairly often, but at the moment he is very happy with Paris as his new home of choice. Just think of the unique café culture, lovely food and wine, the luxuriously blasé feeling of a late Sunday afternoon. Tim's identity might have been largely moulded in Ireland, as he moved to France in his early twenties, but nowadays Paris with its myriad of little cafés and brasseries has a definite home feeling to it.

From New Europeans to the Euro generation

As we amble along the Canal Saint Martin, weaving our way in and out of a crowd of Saturday night art spectators, Sladjana Perkovic inadvertently smiles as I drop the origin question. "When I speak French, people often ask me where I'm from. Before I used to explain my origins, but now I'm not in the mood for that any more. So I say I'm French, but that French is not my mother tongue." Born in Banja Luka, a city in the north-western part of Bosnia, Sladjana came to Paris in her early twenties to study politics and communications. After seven years in the capital, she is not only a lovely incarnation of the quintessential Paris chic, but has also been a French citizen for the past twelve months. As we stop to look at an art installation – a suspended ice ball that slowly dissolves into the shimmering waters of the canal – Sladjana explains that to her France doesn't seem like a foreign country at all. "I have two homes: one in Paris and one in Banja Luka. I feel French and Bosnian at the same time, but when I'm abroad I feel European."

In recent years, the number of young people who, like Sladjana, agree on "European" as a second nationality has been constantly growing. International studies like the Youth and European Identity Project (2001-2004), initiated by researchers from different European universities, as well as most recently the Eurobarometer survey on New Europeans (2011) have shown that an increasing number of under 25-year-olds identify simultaneously as German, Czech or French as well as European. The list of midwives to this Euro generation is long; Erasmus, Schengen and EasyJet being among the most widely cited. Still, it is not just about less bureaucracy, more study loans and cheaper tickets. Feeling European is also a mindset of curiosity, adaptability and cultural passion, as grand as this might sound.

In recent years, the number of young people who, like Sladjana, agree on "European" as a second nationality has been constantly growing. International studies like the Youth and European Identity Project (2001-2004), initiated by researchers from different European universities, as well as most recently the Eurobarometer survey on New Europeans (2011) have shown that an increasing number of under 25-year-olds identify simultaneously as German, Czech or French as well as European. The list of midwives to this Euro generation is long; Erasmus, Schengen and EasyJet being among the most widely cited. Still, it is not just about less bureaucracy, more study loans and cheaper tickets. Feeling European is also a mindset of curiosity, adaptability and cultural passion, as grand as this might sound.

Multiple personalities for the European self

As the notion is gaining more validity, we passively, and sometimes actively, nurture our image as "young Europeans," until we can't solely call ourselves Irish, Bosnian or German any more. This realisation gently oozes in, most often with a reshaping of our social behaviour. The French custom of exchanging la bise in various social contexts is only one habit above many. Language also has its part in this subtly orchestrated personality development. The more fluent we become in another language, the more often we think and dream in it, the more real become our new personality facets. We are still sitting in the same café, three espressos down the line each, when I ask Tim if he has ever felt like he was suffering from a language induced multiple personality disorder.

With a little laugh, Tim assents. "Yes, it's very real and very odd. I think it's only when you reach a good level in a foreign language that you realise the new personality you've developed in the meantime. But no matter how well you speak, there will always be a lack of mother-tongue nuance in your new language, which makes your foreign persona more blunt, more audacious, with an entirely different sense of humour."

With a little laugh, Tim assents. "Yes, it's very real and very odd. I think it's only when you reach a good level in a foreign language that you realise the new personality you've developed in the meantime. But no matter how well you speak, there will always be a lack of mother-tongue nuance in your new language, which makes your foreign persona more blunt, more audacious, with an entirely different sense of humour."

Tim, who speaks English, Gaelic and French, sometimes wonders just when this French self of his emerged. But instead of seeing it as a danger, he enjoys being able to switch around. Sladjana also agrees that seven years in France have changed her a lot. As we walk down the canal towards the Place de la République, where an installation by Japanese artist Fujiko Nakaya envelops passers-by in a gentle mist, Sladjana is thinking about moving. Around us we can only dimly perceive the shapes of the many Parisians who are manoeuvring through the mist, giggling and laughing at the top of their voices every time a volley of wetness showers them from above.

Less politics, more passion

It might be that we are a very fortunate lot, privileged when it comes to social background, education and opportunities in life. But identifying as European is becoming less elitist and is often more of a geographical lifestyle choice than a political motto. Of course, we know that we owe our new freedom to the EU, but we have come to relate to it on a more personal level. It is no secret that this is exactly what Europe and the EU need: less politics, more passion. Less paperwork, more crackers. More often than not, our visions of Europe are sparked on a stroll to our favourite Parisian café, during an exchange year in Dublin or on an evening out in Banja Luka.

Waiting yet again for the inevitable question, this time over beers and a different kind of crackers on another capital curb, I am surprised to notice how I am beginning to face those four little words with less dread and more of a sparkle. "Where are you from?" Without over-simplifying or hiding away in mysterious generalisations, I embark on a discussion about what my cultural background is, where I have lived and where I am currently living, happily juggling my European identities – and everyone else's too. Yes, I am German. And yes, I feel French. I often live in Paris, but you will also find me in London, Berlin, Delhi, or even Melbourne. I am a city lover, an Asia fan, a foreign culture addict, and definitely European.

Waiting yet again for the inevitable question, this time over beers and a different kind of crackers on another capital curb, I am surprised to notice how I am beginning to face those four little words with less dread and more of a sparkle. "Where are you from?" Without over-simplifying or hiding away in mysterious generalisations, I embark on a discussion about what my cultural background is, where I have lived and where I am currently living, happily juggling my European identities – and everyone else's too. Yes, I am German. And yes, I feel French. I often live in Paris, but you will also find me in London, Berlin, Delhi, or even Melbourne. I am a city lover, an Asia fan, a foreign culture addict, and definitely European.

---