Günther von Hagens: dead bodies 'Plastinator'

Published on

Translation by:

Nabeelah ShabbirThe German anatomist has created quite a furore with his ‘Body Worlds’ exhibition throughout Europe. Since November 2006, visitors to the Plastinarium workshop in Guben have observed how corpses are plasticised

Macabre? That’s one way of describing Günther von Hagens’ latest stunt. German magazine Bild alleged that he would sell plasticised preserved corpse pieces as ‘an unusual gift or that perfect ornament for your living room’ to ‘private individuals.’ After general outcry, von Hagens retracted his unlikely business plan comments on 5 February 2008.

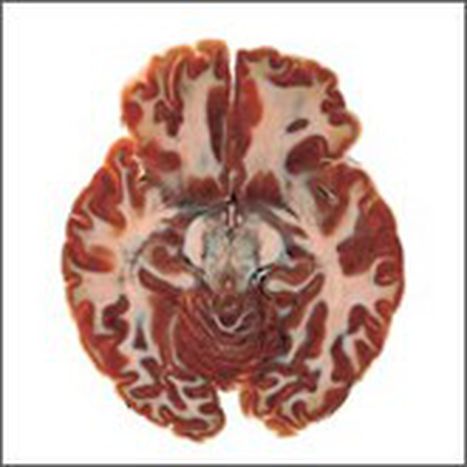

His ‘Plastinarium’ workshop has been open since November 2006 in Guben, a small town near the German-Polish border. Countless people have come to see exactly how his preserved corpses are produced.  Coming into the ‘most unique public plastination workshop in the world,’ you find yourself amongst the living. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons plays softly from loudspeakers above. Brains accumulate on shelves. Plasticised limbs await transformation, like violins awaiting tuning. A group of skeletons wearing bowler hats greet the incoming visitor, a visual reminder of Guben’s hat factory roots. ‘Now I get what this is all about, it's not as scandalous as is made out,’ comments Mateus, an architecture student from Dresden.

Coming into the ‘most unique public plastination workshop in the world,’ you find yourself amongst the living. Vivaldi’s Four Seasons plays softly from loudspeakers above. Brains accumulate on shelves. Plasticised limbs await transformation, like violins awaiting tuning. A group of skeletons wearing bowler hats greet the incoming visitor, a visual reminder of Guben’s hat factory roots. ‘Now I get what this is all about, it's not as scandalous as is made out,’ comments Mateus, an architecture student from Dresden.

Since his first exhibition of plasticised human corpses in China in 1996, von Hagens has found himself having to constantly justify himself and his work. ‘Body Worlds’ has fascinated and horrified more than twenty million people worldwide. In 2004, German magazine Der Spiegel went as far as intercepting emails to accuse von Hagens of illegally ‘working’ on the dead bodies of executed people in China. The 'Plastinator' denies this.

The Plastinator of dead bodies, originally from Tueringen, continues to hit the headlines. And not just because he manipulates his corpses into posing for aesthetic scenes, making them look like poker players or sports stars. Witches too fly over vertebral columns, and characters from the sunken Titanic float around them with their arms flaying. ‘By presenting himself as an artist-anatomist, he stands on the borderline between art and inherited anatomy of artists and Renaissance-era doctors,’ says Käthe Katrin Wenzel, who published her PHd thesis Meat as an art material - objects at the interface of art and medicine (Berlin) in 2005. ‘He is absolutely consistent in the ambivalence of his plasticised forms.’

Butcher’s art, or anatomy?

Being in ‘Plastinarium’ reminds you of being in a butchers; scarlet figures, their veins and arteries visible thanks to a special process, shine in a blue light at the butcher’s counter. In the ‘human pieces workshop’, you are free to touch and pick up the prepared plasticised slabs, which have been sliced to discs of 2.5mm. ‘The technique of plastination is a completely new technology which highlights aspects which have never existed before. That’s why there is a huge gap in terminology on the subject,’ says Liselotte da Fonseca from the University of Hamburg, who is co-editor of a series about the long-term consequences of plastination. ‘It’s a human corpse, but at the same time it is 70% plastic, pigmented and cut and worked on as if it were chopped meat (‘flexible as a baby’s dummy’, as von Hagens himself once put it). For Fonseca, our concepts on art and nature are enlarged in this way.

Yoga Lady, 2005 (Photo: ©Gunther von Hagens, Institut for Plastination, Heidelberg, www.koerperwelten.de)

Yoga Lady, 2005 (Photo: ©Gunther von Hagens, Institut for Plastination, Heidelberg, www.koerperwelten.de)

Meanwhile, von Hagens stands accused of trying to equate art with anatomy. ‘He very often goes for a stylisation of his plastinates which take a step ahead of a simple obligatory pose,’ judges Wenzel in her book. Von Hagens himself confirms this hypothesis of designating one of his creations as ‘aesthetic anatomy’. ‘This person uses the privileges of art like a parasite, to transgress moral and legal frontiers of the human body, and all in the interest of his body limb business. You can consider Stalin an artist too in that case, and forgive him all the sumptuous avenues that he had built,’ criticises Thomas Kliche, another co-editor of the series tracking the consequences of plastination in the long-term.

Post mortem beauty salon

In the self-quipped ‘post mortem beauty salon’ in Guben, tourists can have a photo taken for the family album in a Smart car with a skeleton as co-driver, pass by the Stasi cell which von Hagens has reconstructed or  go to the children’s corner; there, plastic swords await with decapitated heads. At the end of the tour, the real ‘sculptures’ in Plastinarium, which von Hagens wants to present as an ‘anatomical theatre, at the end of a large scientific tradition and European democracy,’ just don’t impress. They seem too random amidst their huge collection. Being human here ‘is converted into a tireless prime subject,’ according to Kliche.

go to the children’s corner; there, plastic swords await with decapitated heads. At the end of the tour, the real ‘sculptures’ in Plastinarium, which von Hagens wants to present as an ‘anatomical theatre, at the end of a large scientific tradition and European democracy,’ just don’t impress. They seem too random amidst their huge collection. Being human here ‘is converted into a tireless prime subject,’ according to Kliche.

The fascination in seeing the final product fades after having seen how many apprentices are devoted to putting the slippery muscles into the correct position and in seeing them breathing in the dust wafting from the cut bones. More than anything, it looks as if someone wants to make transparent all those things which are being produced in that 2500m2 space within the red brick walls of this former clothes factory. Because above all, Guben is a factory, a business, an ‘exposition’, a portrait of a company: art and anatomy sold lucratively together.

Translated from Körperwelten: Eine Scheibe Mensch, bitte