German cinema: Die Welle, wanting to belong

Published on

Translation by:

Ed SaundersThe German remake (‘The Wave’) by Dennis Gansel describes the emptiness felt by the globalisation generation, and premiered in the UK in summer 2008

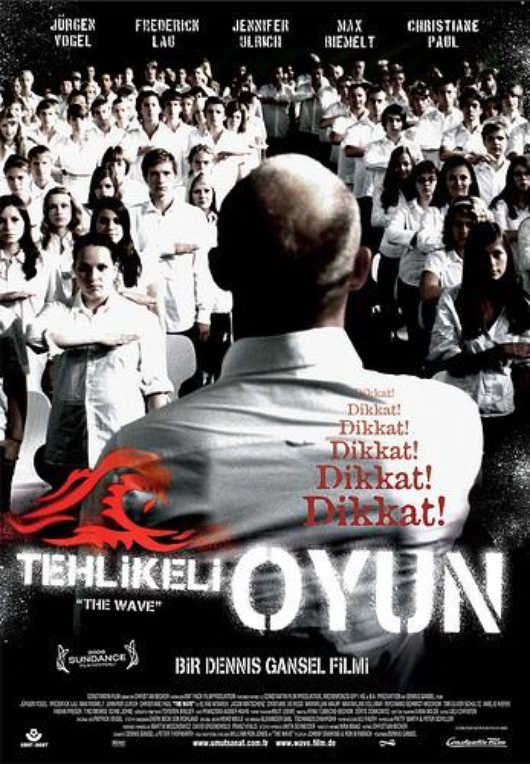

Rainer Wenger (Jürgen Vogel) stands in front of his pupils. The camera pans from behind his head to reveal a group of young people dressed in white, greeting their teacher with a wave-like arm movement. Individual differences cannot be discerned. The comparison with (any) totalitarian youth organisation is intended. Dennis Gansel’s film Die Welle ('The Wave') is adapted from a book of the same title by the American author Morton Rhue, in which a college teacher tries a social experiment on his pupils. Is a dictatorship still possible today?

A few scenes earlier the same shot is shown, only Rainer Wenger is standing in front of a very different bunch of kids: swots, punks, chavs, hippies, and hip-hop wannabes in no particular order. They aren’t all intelligent, nor are they all successful, not all of them are loved – but they are individuals with their own desires, problems and attitudes. They have chosen the course ‘autocracy’ for project week, led by their favourite teacher who is anything but authoritarian. He spent five years living in squats in Kreuzberg, took his Abitur through further education classes, and displays a Fuck Bush sticker on the letterbox outside his home, a houseboat. It’s obvious that he has fought for the social conditions which his pupils take for granted.

Their problems are quite different. They live in a society in which the most-searched term on the web is Paris fucking Hilton, and everyone ‘just thinks about themselves’. They question what there is left to rebel against, and they are happy when someone takes away some of the countless decisions they face at school.

Their problems are quite different. They live in a society in which the most-searched term on the web is Paris fucking Hilton, and everyone ‘just thinks about themselves’. They question what there is left to rebel against, and they are happy when someone takes away some of the countless decisions they face at school.

The sense of community feeling is weak – in the drama rehearsal no one can decide on a script, and the waterpolo game is a mess. Despite the general feeling of isolation they agree that a dictator would be impossible in modern Germany, ‘we’re too enlightened for that’. Rainer Wenger seizes on this suggestion, and decides on a group experiment to investigate the question. Every day of project week he introduces a new element of a dictatorship: standard uniform, common greeting, a name for the movement, a leader. He himself is elected by the pupils.

The group develops a dynamic - other pupils are excluded, those with the least self confidence gain courage through the group’s protection, ‘power through discipline’, ‘power through community’ and ‘power through action’ is the rule of three they agree upon. The energy that develops from the new cohesion focuses the formerly slack pupils. They are glad of the new-found meaning in their lives, which obscures their individual problems. Only Caro rebels.

The films stays close to the young people and their subculture: the wave logo is sprayed as a graffiti tag across town, they have a wave party where they play hip-hop on the radios of wrecked cars, drink, deal and smoke weed anyway. A quick editing sequence and a few scenes with a hand-held camera almost give the impression of an MTV music video. These scenes show that although everyone is enthusiastic about The Wave, it has an anarchic quality, not an authoritarian one. So it seems artificial at the end when Rainer Wenger describes The Wave as an anti-globalisation movement, and an alternative to the present pressure to succeed, which makes the ‘rich richer, and the poor poorer’. To enthusiastic applause from the members of The Wave, Marco is brought forward – under Caro’s influence he is supposed to have become a ‘traitor’. Only at this point is the experiment brought to a close. Authority has become a fixed part of the identities of some of the pupils. It’s that easy.

Translated from Die Welle - Sehnsucht nach Inhalten