Europe’s lobbies: Brussels comes second to Washington

Published on

Translation by:

Annika ThorntonThe image of the lobbyist is a part of the Brussels political landscape. These groups work in the spotlight, but also have a consulting role in the legislative process. Is this mature democracy or a skills deficit in Europe?

According to the Stubb report on the constitutional affairs committee of the European parliament, around 15, 000 lobbyists and 2, 500 organisations liven up Europe's institutions. For its concentration of ‘interest representatives’ - better known as lobbyists - Brussels is second only to Washington.

European bubble: transparent inside and out?

This number is impressive, but if we take into account every professional body, even those part-time, who are involved in the task of ‘interest representation’ (collecting information), the actual figure would be more like 100, 000. This was the calculation of industry veteran Daniel Gueguen, theoretician and lobbying expert, founding member of public affairs consultancy Clan Public Affairs.

This number is impressive, but if we take into account every professional body, even those part-time, who are involved in the task of ‘interest representation’ (collecting information), the actual figure would be more like 100, 000. This was the calculation of industry veteran Daniel Gueguen, theoretician and lobbying expert, founding member of public affairs consultancy Clan Public Affairs.

According to the European commission, this category includes anyone who practices ‘activities carried out with the objective of influencing the policy formulation and decision-making processes of the European institutions.’ Syndicates, NGOs, multinationals and European trade associations aspire to be represented where it counts: in Brussels, they are influential in 75% of national legislation.

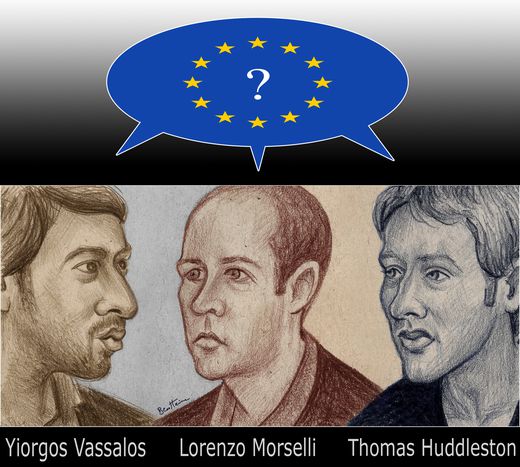

But who are these lobbyists? The image of the ‘shady character’ that plots in the shadows has been put aside. Those sitting at the head table of the European legislative process all know each other; one of whom is Tom Huddleston, policy analyst for the Migration Policy Group think tank, who defines the ‘Brussels bubble’. ‘There is relative transparency inside the bubble,’ points out the young American. ‘You know the person, the donors, the different position - everyone understands each other really well. It is s true that transparency is important outside the European bubble; outside we need more binding rules.’

The essential lobbyist

And that is not all. The people involved in this line of work consider Brussels to be a far more transparent platform than it is at a national level. French-Italian parliamentary assistant Lorenzo Morselli is convinced of it. ‘Without the lobbyists we couldn’t even legislate,’ he adds. It seems paradoxical, but the EU, which is often accused of institutional gigantism, suffers from cultural dwarfism. ‘Given the amount of legislation and the short time we have, we need those competences,’ Morselli admits. 'This way the skills of those who propose a resolution to a problem are properly considered.'

'You are not slaves to those guys. You know they represent someone, they have particular interests, you know what they might try to do when they give you their arguments. If you are a good lawmaker you have to hear the whole story before you decide – trade unions, industries, enviromental organizations, and so on.’ The essential lobbyist is an integral part of the decision-making process. ‘An opposing power that brings solutions’: this is the definition of sector guru Daniel Gueguen, who classifies a good lobbyist as someone highly qualified, with technically and financially credible propositions.

The lobbyist register

A lobbyist represents their own people. They are responsible for their own financial backers. This raises the problem of democratic bias with respect to the whole population. The European commission for administrative affairs, audit and anti-fraud, in particular commissioner Sim Kallas, tried to resolve this in 2005 with the European transparency initiative. It paved the way for the voluntary lobbyist registry in June 2007. Note the ‘voluntary’ part. The commission strongly encourages it, and the information is made public via the internet. The model follows that of the United States, where the activities of the lobbyist are made public, including the names of clients and financial backers.

The register has been greeted coolly by everyone. It doesn’t satisfy Yiorgos Vassalos of the Corporate Europe Observatory, employed to ensure maximum transparency in the legislative process. ‘We want to know who finances the lobbyists. Our proposal is to have a scale that permits comparison with the relative weight of the companies and lobbyists. How much money does a lobby spend on a campaign, for instance, to show that CO2 emissions (of a brand of cars for example) are not damaging? We would like to know.’

Daniel Guéguen agrees that he would like more transparency. He feels dubious about the register. ‘It’s too vague,’ he maintains. ‘What should I record? My job as a lobbyist? My work as an analyst? Why only be concerned with lobbyists? The European commission needs committees of experts in order to legislate. How are they formed? Who influences them? We just don’t know.’

Comitology?

According to Alter EU, a coalition of organisations employed for maximum transparency, there are more than 1, 200 groups of experts. They are formed from the same commission with the aim of assisting the legislative process. The criterion of appointment and the names of their members are not published. This phenomenon has come to be known as comitology*. The stages of comitology are so important that Daniel Guéguen has published a second edition of European Lobbying - The First Practical Book on European Lobbying Methodology (2007). The manual is full of advice and tactics to successfully approaching these groups’ being in a committee or influencing one equates to legislating.

According to Yiorgos Vassalos, expert groups are advisory bodies formed at the beginning of the legislation process. More than half are members coming from the industries. ‘55% of the experts come from governments. 35% come from the world of industry and in some cases, they are more than half. For instance in the textile, biotechnology and climate change sectors, the European commission is formulating policies based almost wholly on the advice of those stakeholders who have a direct commercial interest.’ Vassolos uses the issue of ‘clean carbon’ as an example, which is entrusted to a group of experts representing competing companies Enel, Edf and Siemens. They comprise a low percentage of representation from environmental agencies.

From committees to lobbyists to those who wish to remain anonymous: for anyone outside the bubble, deciphering the origins of European legislation is unfathomable. ‘The problem is the democratic deficit,’ explains Tom Huddleston. ‘I think that people wouldn’t care so much if European democracy was more developed. The fear of lobbying is a symptom of the democratic deficit. Lobby would not disappear if we became more democratic. But if I had more trust in the elected officials, then I don’t mind if the elected official get opinions from different organisations.’

So does this mean more transparency according to the American model? Lobbyists and parliamentary members prefer to keep quiet. An MEP perhaps doesn’t wish to have their sympathy for lobbyists advocating that nuclear energy is clean, to become public knowledge. In the same way those who work with nuclear energy don’t want to reveal their clients. ‘People fear being coupled with certain others,’ continues Lorenzo Morselli. ‘In America there is more transparency. It is a physiological thing that you have to come to terms with, to accept that some details of your personal life are public.’

In anticipation of this cultural gap, you can kill time with the Worst Lobby awards 2008. In 2007 a joint victory was awarded to BMW, Daimler and Porsche. The nominations for 2008 are now open.

*Comitology: An English term to describe the work of committees of experts who take part and shape legislative proposals by the European Commission. This English term is used in Italian political science

Translated from Le lobby in Europa: gruppi di pressione alla luce del sole