Daniel Libeskind's towering success

Published on

Daniel Libeskind, the architect recently commissioned to redevelop the WTC, embodies the spirit of Europe: a free thinker, a free mover, who has drawn upon his diverse influences and used them to great effect all over the globe.

Architecture is not just about construction but also about cultural and historical expression, and it is in this that Libeskind excels. Born in Poland in 1946, Libeskind moved to Israel and then America with his parents to escape Communist oppression and anti-Semitism. Hailed as a musical prodigy, Libeskind decided to give up playing professionally to pursue a career in architecture and, after completing his professional architecture degree in New York, returned to Europe to do a post-graduate degree in History and Theory of Architecture in the UK. The importance of history has since been a recurring theme in Libeskind's work and is perhaps one of the reasons why his works are so striking, managing to capture the ephemeral in the tangible.

Architecture is not just about construction but also about cultural and historical expression, and it is in this that Libeskind excels. Born in Poland in 1946, Libeskind moved to Israel and then America with his parents to escape Communist oppression and anti-Semitism. Hailed as a musical prodigy, Libeskind decided to give up playing professionally to pursue a career in architecture and, after completing his professional architecture degree in New York, returned to Europe to do a post-graduate degree in History and Theory of Architecture in the UK. The importance of history has since been a recurring theme in Libeskind's work and is perhaps one of the reasons why his works are so striking, managing to capture the ephemeral in the tangible.

The Jewish Museum in Berlin is one of the most striking examples of Libeskind's architecture as the building itself emulates the pain and destruction of the Holocaust. The decision to undertake the Jewish Museum project was a difficult one to make for Libeskind, whose own parents were Holocaust survivors. On receiving an honorary doctorate from Humboldt University in Berlin, Libeskind claimed he thought of himself "not as an architect of just another nationality doing a German project, but rather as someone who has no identity; himself a product of the Holocaust era".

A Pole in cowboy boots

The Jewish Museum was a turning point in Libeskind's career as, although he was lecturing in universities across the world and already celebrated in academic circles, his designs had never come to fruition and, as a result, were seen to be largely theoretical abstractions. Libeskind's recent success has drawn criticism from some architects who accuse him of pandering to the public in stunts such as wearing cowboy boots to assert his 'American-ness' in the competition for the World Trade Centre project. Perhaps it is Libeskind's working class background that sets him apart from most fellow architects and allows him to dismiss these claims by pointing out that "architecture's not for an elite. It's the real world."

New projects

Not content with building museums and galleries, Libeskind went all out in his efforts to win one of the most important contracts of the past 50 years: the reconstruction of Ground Zero. He succeeded. Yet again, he has had to design something which is so much more than just a building; something which stands out as a monument to those who died, while providing an image of strength and hope for the future.

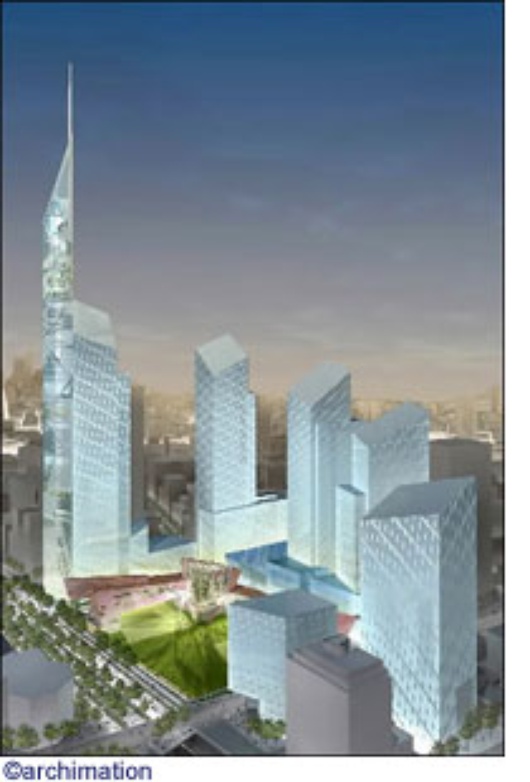

Most people faced with such a challenge would focus entirely on that single project, but Libeskind has his fingers in lots of other pies. Most recently, he won the rights to build three skyscrapers in Milan (where in 1985 he founded an architecture school, the 'Architecture Intermundium'), the first to be built in the city for over 40 years. Other European projects include a performing arts centre in Dublin, the largest shopping centre in Europe (to be built in Switzerland) and even an opera production. The sheer variety of projects and countries is impressive and illustrates the significance of architecture as an expression of post-national identity.

A nomadic existence

Having grown-up in Poland, Israel and America, Libeskind has continued to move from country to country. His youngest daughter, born in Italy while he worked there, is mainly German-speaking having been brought up in Berlin where he and his family lived during the 10 years it took to complete the Jewish Museum.

Rather like his architecture, which transcends borders between countries, between past and present, between pain and hope, Libeskind is difficult to pin down. As he said in an interview with Giles Worsley, home is "not here or there, it's a kind of journey…People identify [with] some piece of ground, some place, but it is illusory because the world is global".