Christmas in Bethlehem: immigrant joys, flirty policeman and the Great Wall

Published on

Due to relative peace between Israel and Palestine, hordes of pilgrims hurried to Bethlehem, West Bank, in search of spiritual excitement of being close to the places where, according to the Bible, Jesus was born. For the locals it is a great opportunity to sell whatever tradable there is.

Bethlehem is close to the Israeli/West Bank border and, if not pilgrims, would probably live in relative isolation. However, both combating sides earn a lot from tourists every year, so the borders should better be open, provided there is no open warfare. Being in Bethlehem on Christmas is particularly interesting, because all of the sudden the town becomes the centre of religious world, and many people are drawn to it in excitement. Not all are religious - some simply search for the special atmosphere. And for someone like me it's a great chance to observe and hopefully meet all kinds of people. So when my Filipino neighbours invited me to join their trip (the invitation came at around 1.30 am; we left the house in four hours), I did not think twice.

Getting to the West Bank from Israel is really easy, at least with a tourist bus. There are no checks and no queues whatsoever. Buses stop at a big parking lot, guarded by special tourism police of the Palestinian Authority. What might strike a visitor, fed with so many tragic stories about Palestine, is the normalcy of the visible life there, people's business and leisure activities. Picturesque valleys covered in trash, pretty houses made of yellow bricks, workers sweeping streets and churches, and just about everything else, obviously, bears no sign that the big wall, built to separate Israel from the West Bank, heavily armed soldiers and disputed areas are just a few kilometres away.

And so we (probably about a hundred Filipino guest workers and me) hurried to the St. Catherine's Church, which was the first stop on our trip.

We were as touristy as tourists can be - jumping from one place to another, taking hundreds of photos. Not because the place was particularly outstanding, but because, as I could clearly observe, taking photos is an even stronger source of excitement than religious feelings to the guest workers, who are staying here for several years, underpaid, discriminated against, and, most importantly, cut off from their families. Thus the 'virtual family' perspective was always there. Taking photos to show where they visited was as important as the actual visit. Standing with their backs against the altar was not a problem to them, as long as the longed-for kids see their mama or papa in a beautiful background.

We were as touristy as tourists can be - jumping from one place to another, taking hundreds of photos. Not because the place was particularly outstanding, but because, as I could clearly observe, taking photos is an even stronger source of excitement than religious feelings to the guest workers, who are staying here for several years, underpaid, discriminated against, and, most importantly, cut off from their families. Thus the 'virtual family' perspective was always there. Taking photos to show where they visited was as important as the actual visit. Standing with their backs against the altar was not a problem to them, as long as the longed-for kids see their mama or papa in a beautiful background.

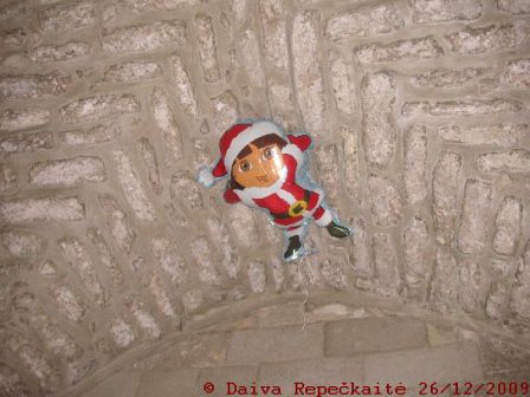

I didn't see any of the guest workers praying or even quietly sitting and contemplating in the church. Happy smiles and camera flashes shone on the church's inner gardens, naves and althars. Since it was early, there were not so many people apart from us. Yet there were some signs of other people's visit:

I didn't see any of the guest workers praying or even quietly sitting and contemplating in the church. Happy smiles and camera flashes shone on the church's inner gardens, naves and althars. Since it was early, there were not so many people apart from us. Yet there were some signs of other people's visit:

Someone's balloon escaped and got stuck for life under the arch.

Someone's balloon escaped and got stuck for life under the arch.

Afterwards we had a chance to walk around a bit. Locals were approaching us in every step with the panoramic photos and religious attributes they had to sell. Rosaries for 5 NIS, cribs for 40 NIS... We went into several nearby stores to compare the prices. The stores offer both 'deeply' religious symbols and 'pop-cultural' Christmas attributes. If you say that Christmas is too commercialised in Europe, go to Bethlehem and see it more extremely. Well, having in mind how few economic opportunities the locals have, it's not surprising that they try to sell anything that tourists could buy.

As tourists-pilgrims, we could not observe much of the town life, unfortunately. Some of the interesting things were the omnipresence of Palestinian flags, just like that of Israeli flags in Israel.

As tourists-pilgrims, we could not observe much of the town life, unfortunately. Some of the interesting things were the omnipresence of Palestinian flags, just like that of Israeli flags in Israel.

If you are on an organised tour, you might even not notice that Christianity doesn't have a monopoly in the town.

If you are on an organised tour, you might even not notice that Christianity doesn't have a monopoly in the town.

As we wait on the parking lot for our bus to proceed with our trip, a Palestinian policeman approaches me and several Filipina women as we show each other our photos. "Hi, how are you?" he says. I tell him that we are doing just great, saw the church and are about to travel further. As if not even noticing the Filipina guest workers, he starts talking to me. I tell him that I come from Lithuania and currently live in Tel Aviv. With self-confidence comparable to that of Israelis, he asks me to leave him his phone number and come visit again. I tell him that I don't give away my phone number to people I know for about 10 min., which sort of surprises him. I tell him about my experience of leaving my phone number to quite several Israelis (some of whom promised to show me the city, etc) only to realise they were never going to call (as my friend S. recently explained, it's like a game: men compete how many numbers they can get, women compete how many drinks they can get for free. My friend A. nicely summarised this culture: "Men ask for phone numbers... to impress other men"). The policeman said he would definitely call me. In the end I took his phone number and told him that I will call him when I want to, and I definitely will if I go back to the West Bank. He promised to take me to his hometown Hebron.

As we wait on the parking lot for our bus to proceed with our trip, a Palestinian policeman approaches me and several Filipina women as we show each other our photos. "Hi, how are you?" he says. I tell him that we are doing just great, saw the church and are about to travel further. As if not even noticing the Filipina guest workers, he starts talking to me. I tell him that I come from Lithuania and currently live in Tel Aviv. With self-confidence comparable to that of Israelis, he asks me to leave him his phone number and come visit again. I tell him that I don't give away my phone number to people I know for about 10 min., which sort of surprises him. I tell him about my experience of leaving my phone number to quite several Israelis (some of whom promised to show me the city, etc) only to realise they were never going to call (as my friend S. recently explained, it's like a game: men compete how many numbers they can get, women compete how many drinks they can get for free. My friend A. nicely summarised this culture: "Men ask for phone numbers... to impress other men"). The policeman said he would definitely call me. In the end I took his phone number and told him that I will call him when I want to, and I definitely will if I go back to the West Bank. He promised to take me to his hometown Hebron.

In fact, even though it was the most ordinary flirting situation, the Weltschmerz I had was weighting on my shoulders to an almost unbearable level. Here I was, finally visiting the West Bank, a tourist, free to go where I want to, talking to this local, wishing to be kind and sweet and culturally sensitive to him. Obviously, for him no boundaries mattered that moment. In his world we were simply a man and a woman, as if the concrete wall, the war and its 'cold peace', the different identities and cultures did not exist. Only in my world it all existed and reminded me of themselves: the asymmetric power games, the wall, the fact that I was free to come to live in Israel and go back to Europe if I don't like it, as well as to visit the West Bank and leave again, and use the hospitality of the guest workers, who, separated from their families by forces of global capitalism, were now chatting and chuckling all around me, enjoying their religious-visual pleasures, while I was looking for polite ways to refuse leaving my phone number to a Palestinian policeman on duty... Just like months ago in Japan, I felt I was undeservingly granted privileges that would be so much help to the other people near me, while they, in fact, had no regrets over not having these privileges and enjoying being nothing more but people, men, women, mothers and fathers, Christians...

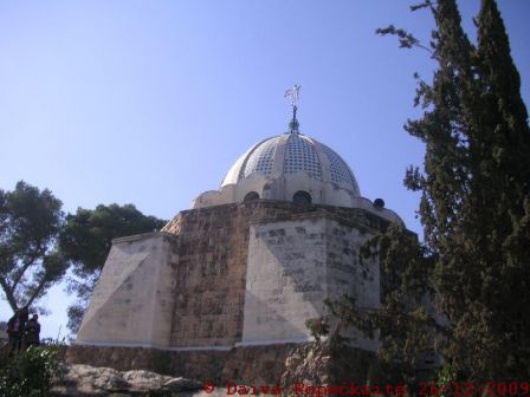

When the bus finally opened, we went on to the Shepherd fields, where the Church of Nativity is.

The tiny church was standing there in serenity, while plastic chairs were put in a shade and a Filipino priest, wearing a cassock with Polish (!) inscriptions, started a Filipino mass. It was quite interesting that the readings and prayers were in English, while the sermon and chanting was in Tagalog. The priests switched to English whenever they were quoting the words of Jesus, too. After the mass the guest workers loaded their rosaries, icons, crucifixes and other purchased religious paraphernalia onto the table (which served as an altar) to get a blessing for them.

The tiny church was standing there in serenity, while plastic chairs were put in a shade and a Filipino priest, wearing a cassock with Polish (!) inscriptions, started a Filipino mass. It was quite interesting that the readings and prayers were in English, while the sermon and chanting was in Tagalog. The priests switched to English whenever they were quoting the words of Jesus, too. After the mass the guest workers loaded their rosaries, icons, crucifixes and other purchased religious paraphernalia onto the table (which served as an altar) to get a blessing for them.

The Shepherd fields is a nice green area, really worth visiting.

Afterwards we went back to Israel. Not so easy, we all knew.

As we waited in a queue at the border, we all had passports in our hands and bags prepared for inspection. However, two armed soldiers got on the bus, looked around and let us go. As we entered the territory of Israel, we were met with this poster:

As we waited in a queue at the border, we all had passports in our hands and bags prepared for inspection. However, two armed soldiers got on the bus, looked around and let us go. As we entered the territory of Israel, we were met with this poster:

Does that sound convincing? :) Hopefully, one day it will become reality.

Does that sound convincing? :) Hopefully, one day it will become reality.