Choose a language - Belarusian or Russian

Published on

Translation by:

Sarah Meleleu

Sarah Meleleu

In Belarus opinions do not only differ on the domineering president Lukaschenko, who has announced a general election for 28 September

Should the word ‘president’ in Belarus be capitalised or not? Linguist Smitser Sauka from Minsk has a clear opinion on this: the word is not a proper noun, rather the description of a position – and Sauka thinks that such words in the Belarus language should not, on principle, be capitalised. In the Belarus spelling reform that state president Alexander Lukaschenko recently established, however, it was determined that his official title will be capitalised until at least 2010. For Sauka, an objector to the spelling reform and member of the opposition party Belarusian National Front (BNF), the reform serves only to keep the subservient spirit of the Belarusians alive.

Should the word ‘president’ in Belarus be capitalised or not? Linguist Smitser Sauka from Minsk has a clear opinion on this: the word is not a proper noun, rather the description of a position – and Sauka thinks that such words in the Belarus language should not, on principle, be capitalised. In the Belarus spelling reform that state president Alexander Lukaschenko recently established, however, it was determined that his official title will be capitalised until at least 2010. For Sauka, an objector to the spelling reform and member of the opposition party Belarusian National Front (BNF), the reform serves only to keep the subservient spirit of the Belarusians alive.

The spelling reform is only an example of how politically heated the discussion about language in Belarus has become. With the state independence in 1991 Belarusian was defined as one language after the motto ‘one state – one nation – one language’. But not all Belarusians agreed to become re-educated from their daily language Russian to the national language of Belarusian. Alexander Lukaschenko, first and only state president of the country since, seized on this sentiment during his 1994 election campaign and afterwards.

Only two main language exist in the world: Russian and English

‘Belarusian is a poor language,’ determined Lukaschenko during a speech at the time. ‘Only two main languages exist in the world: Russian and English.’ And he allowed consultation of the public as early as 1995 whether Russian next to Belarusian should become the state language again. The result: over 80% of the views were for the reintroduction of Russian.

However it is not quite so easy as that. And not only because the objectors to the bilingual public voice had the opportunity to voice their opinion in the state media before the referendum. Many Belarusians appear to be particularly proud of ‘their’ Belarusian language, despite not being able to use it. At any rate the language statistics from the census of 1999 can be interpreted in this way: more than 70% of all those asked said Belarusian was their mother tongue, although at the same time only just under 40% declared that they also actually used it in every day life.

Language of protest?

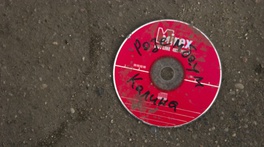

Supporters of the national language of Belarus are organised nationwide in the ‘Belarusian Language Association’, which is, according to a statement by its chairperson, Aleh Trusay, the largest legal NGO in the country. In the capital city Minsk, the Belarusian Language Association has its all too small branch near the State Linguistic University, where they sell books and CDs in Belarusian.

Supporters of the national language of Belarus are organised nationwide in the ‘Belarusian Language Association’, which is, according to a statement by its chairperson, Aleh Trusay, the largest legal NGO in the country. In the capital city Minsk, the Belarusian Language Association has its all too small branch near the State Linguistic University, where they sell books and CDs in Belarusian.

Despite its campaign for linguistic rights, the NGO does not see itself as a political organisation. And Belarusian has always been an important symbol of the protests against the presidential rule of Alexander Lukaschenko: demonstrators were beaten up by the militia, because they shouted slogans in Belarusian or spoke to each other in this language. School children and parents who apply for school education in Belarusian are quickly labelled political trouble-makers.

But it is yet to be concluded that Belarusian is the language of the opposition against state president Lukaschenko. Jurij Drakoschrust, political commentator of the Belarusian editorial Radio Free Europe, preaches caution on such judgements. ‘Amongst the Russian speaking politicians there are equally patriots who are for Belarusian independence,’ says Drakochrust. Important opposition parties like, for example, the liberal United Citizens’ Party, conduct their election campaigns primarily in Russian.  Most speakers of Belarusian still belong to the older generation, live in the countryside, have no university degree and long for the Soviet Union rather than the EU. Aside from that there are admittedly more and more young people and educated people in the cities, especially in Minsk, for whom Belarusian has a rebellious image. On social networking websites like Facebook or Hospitality Club they not only leave each other Belarusian messages, but they also all have friends from the west on their contact lists. And if they made the decision about the Belarusian spelling reform, they would surely have begun the word ‘President’ with a small letter.

Most speakers of Belarusian still belong to the older generation, live in the countryside, have no university degree and long for the Soviet Union rather than the EU. Aside from that there are admittedly more and more young people and educated people in the cities, especially in Minsk, for whom Belarusian has a rebellious image. On social networking websites like Facebook or Hospitality Club they not only leave each other Belarusian messages, but they also all have friends from the west on their contact lists. And if they made the decision about the Belarusian spelling reform, they would surely have begun the word ‘President’ with a small letter.

The author, Mark Brüggemann, is a member of the German writers correspondence network n-ost, based in Berlin

Translated from Wahlen in Weißrussland - ein Land mit gespaltener Zunge