Brian Aldiss: 'I told Kubrick it was impossible he make a film of my story'

Published on

The British science fiction author, 82, on working with Hollywood greats, being caned for 'telling stories' at school and Europe being a 'wonderful idea'

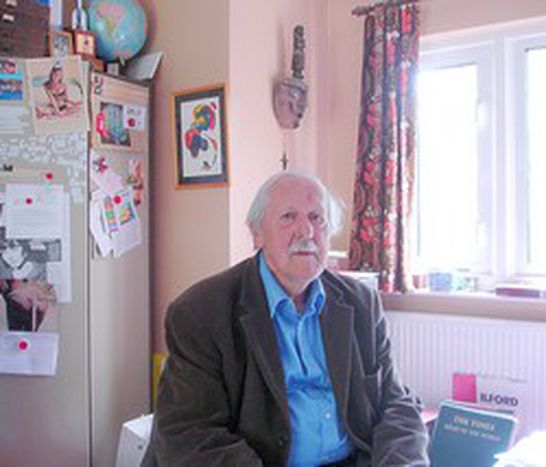

I catch Brian Aldiss is in the midst of having his portrait painted. Life’s not too bad for a man of 82, who is currently preparing for yet another science fiction convention, where adoring fans are waiting for him to sign his autograph on their t-shirts.

You could also include a few notable Hollywood film producers amongst Aldiss' fans; Roger Corman, Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg have all come rapping on his door in the past to ask his permission to adapt both his general and science fiction stories to the big screen. Three notable successes include: Frankenstein Unbound (Roger Corman, 1990), A.I. ('Artificial Intelligence') (2001) and Brothers of the Head (Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe, 2006). Even Britain’s Queen awarded him with an OBE in 2002 for his services to literature.

The Kubrick-Spielberg circle

Working with such famous film directors has certainly been remunerative and exciting, but not necessarily always 100% satisfactory. ‘Working with Corman was an extremely good experience for me,' says Aldiss of the prolific independent filmmaker, who directed the 1990 horror John Hurt and Bridget Fonda vehicle Frankenstein Unbound, set in 19th century Switzerland. 'He invited me and my whole family to the set, a palazzo (palace) owned by the local Mayor of Bellagio on the shores of Lake Como. He had lent us the location on the condition he be given a role as an extra on the set.' Aldiss remembers only one artistic difference with Corman, over the inclusion of an extra scene when Frankenstein goes mad and destroys a laboratory. 'But despite our differences, the scene made it into the movie.'

In A.I., a modern short story retelling of the Pinocchio fairytale, Aldiss's experiences of collaborating with two of Hollywood’s greatest directors, Kubrick and Spielberg, brought home to him the old adage ‘when you sell something to the movies, take the money and run - in other words, just let them do what they want with the movie, instead of arguing with them!’ Aldiss learnt to appreciate the difficult task such producers have in adapting prose to movies. 'You can have thousands of scenes in a book,' observed Kubrick once, 'but you can’t afford the time or the money to reproduce every scene in a film.’

Working with Kubrick was 'interesting', says the writer, but they clashed too. 'In the movie, he wanted the android boy to meet the Blue Fairy and become a real boy,' recalls Aldiss. 'I obstinately resisted this notion - I was astounded by the very suggestion. I had always wanted to work with the genius that was Kubrick, but after a year’s collaboration together, he chucked me out.’ In a wistful manner he remembers the departing shot he fired at Kubrick: ‘It’s impossible for you to make a film of my story!' ‘Yes I can,’ retorted the director - although he died on 7 March 1999, just before shooting was due to start on A.I. Spielberg eventually took over the reins to complete the movie in 2002. Co-starring Jude Law (for which he was nominated for a Golden Globe award), the film was dedicated to Kubrick's memory.

Far from Hollywood-beginnings

Far from Hollywood's lights, Aldiss was born in Norfolk in south-eastern England, to a department store manager father. He read omnivorously - everything from Homer’s Odyssey to the works of Thomas Hardy, Patrick Hamilton, Jean-Paul Sartre and Stendhal. He started telling tales at an early age at private boarding school. There he served his apprenticeship of how to spin a good story and get his fellow pupils always begging for more, by creating a cliff-hanger at the end of each episode of his serial ghost stories, so they had to wait till the next day to find out what happened next. Unsurprisingly, Aldiss was often punished by his teachers for talking after ‘lights out’ in the pupils’ school dormitory. He regularly got six with the cane on his pyjama bottom, to which he comments, ‘nothing that any literary critics have done since has been more vicious.’

Aldiss served in Burma and Indonesia during World War Two, before fulfilling his dream of becoming a full-time professional writer. ‘I had the option as a writer of starving in a garret, or starving in a bookshop’ - he took the latter option, and started his professional writing career as a bookseller based in Oxford. After being invited to write a humorous column about life in a fictitious bookshop for prestigious book trade weekly magazine The Bookseller, his column attracted the attention of Charles Monteith, then-editor at British publishers Faber and Faber. They were later to collaborate on Aldiss's first book The Brightfount Diaries (1955), based on pieces from his Bookseller column. ‘I am often asked what has inspired me,’ says Aldiss. 'In fact, it is life - life, the universe and everything.'

Super state

In 2002 Aldiss published Super-state, a comic novel about a Europe some forty years into the future, packed full of contemporary recognisable characters. ‘It's the great social experiment of our time,' he says, of the European Union. 'A wonderful idea. Europe had, for centuries, been plagued by religious obsessions, dynastic and territorial ambitions, which have stained the continent with blood from one end to another. Now instead of war, we sit round a table in Brussels and argue it out. It’s fantastic; I don’t understand why more people don’t marvel about it.'

‘Turkey should undoubtedly join,' he adds. 'It would be an advantage for Europe as a secular state, helping in the struggle against extremism.’ He knows the country well, as his son has business interests there. His own father also fought in World War One at Gallipoli, where Atatürk, the founder of modern Turkey, had inscribed on the Turkish War Memorial that he erected: Yes once we fought and died on this ground, and now your sons are as my sons, and all are equally regretted.

The artist has finally finished her sketch - in front of my eyes, Aldiss has been etched in the picture as a casually dressed, irascible 82-year-old, still with a youthful glint in his eye, and no doubt many more years of writing left.

Watch out for two new books by Brian Aldiss that are out this summer: H.A.R.M., about Britain getting to grips with terrorism, and Walcott - a story about a fictional family set in Britain during the 20th century, some of which is based on the writer's own experiences

Homepage photo: Aldiss in his Oxford back garden, 12 June 2007 (Nicholas Newman)