At the heart of ‘The Orange Revolution’ - Part 2: The children of Ukraine

Published on

Translation by:

Morag Young

Morag Young

The second in a series of three reports from Ukraine during the third round of the presidential elections: Does this revolution mark the revival of Ukrainian nationalism?

Alexis ‘shoots up’ a cigarette, as they say in Russian slang. With all the wisdom of his 20 years, he protects District 0 at the heart of the camp day and night, and shares guard duty with other young men. He belongs to one of the four or five militia formed on 21 November. His is called ‘The children of Ukraine’. Dressed in combat uniform, Alexis is in one of several small army vehicles which serve as camp canteens. In these vehicles, permanently supplied by fatigue militia and equipped with wooden stoves, soup and water for tea can be heated up. Alexis explains the reasons behind this quasi-military discipline. “We’re afraid that the police will turn up unannounced and throw us out”. There have been quite a few scares during this revolution, especially during the first week. Brice Bader, a Frenchman who has been living in the camp for a month with his Ukrainian girlfriend, tells me, “One evening we were called together. We were told, ‘those who want to leave can; those who want to stay are welcome to do so’. The news spread that the army was going to try to throw us out and that Russian solders had arrived, dressed in Ukrainian uniforms”. This information has since been confirmed by the BBC which noted the movement of troops that evening, 28 November. If the presence of Russian soldiers in Ukrainian uniforms is not a known fact, the presence among State representatives of members of the FSB, the former KGB, is more likely. “We put our vehicles in the front line, the men behind them and the women in the tents,” Brice continues. “We were asked to keep a piece of paper with our blood group written on it in our pockets, just in case…nothing happened that night though and I think that that was the moment the revolution was won”. Indeed, the army hasn’t gone through the motions of intervening since then and, in reality, the only thing to occupy the soldiers are a few sorties to check that Yanukovich's supporters are not coming to make trouble in the camp.

Alexis ‘shoots up’ a cigarette, as they say in Russian slang. With all the wisdom of his 20 years, he protects District 0 at the heart of the camp day and night, and shares guard duty with other young men. He belongs to one of the four or five militia formed on 21 November. His is called ‘The children of Ukraine’. Dressed in combat uniform, Alexis is in one of several small army vehicles which serve as camp canteens. In these vehicles, permanently supplied by fatigue militia and equipped with wooden stoves, soup and water for tea can be heated up. Alexis explains the reasons behind this quasi-military discipline. “We’re afraid that the police will turn up unannounced and throw us out”. There have been quite a few scares during this revolution, especially during the first week. Brice Bader, a Frenchman who has been living in the camp for a month with his Ukrainian girlfriend, tells me, “One evening we were called together. We were told, ‘those who want to leave can; those who want to stay are welcome to do so’. The news spread that the army was going to try to throw us out and that Russian solders had arrived, dressed in Ukrainian uniforms”. This information has since been confirmed by the BBC which noted the movement of troops that evening, 28 November. If the presence of Russian soldiers in Ukrainian uniforms is not a known fact, the presence among State representatives of members of the FSB, the former KGB, is more likely. “We put our vehicles in the front line, the men behind them and the women in the tents,” Brice continues. “We were asked to keep a piece of paper with our blood group written on it in our pockets, just in case…nothing happened that night though and I think that that was the moment the revolution was won”. Indeed, the army hasn’t gone through the motions of intervening since then and, in reality, the only thing to occupy the soldiers are a few sorties to check that Yanukovich's supporters are not coming to make trouble in the camp.

500 years of oppression

However, some people have grown weary of waiting for an enemy who doesn’t come and defending a revolution whose happy ending already seems assured. They want more; they want to defend their fatherland. People like Ochsana, who was a member of Black PORA, which likes to think of itself as being independent from the official Yellow PORA. Ochsana is ready to continue her activism after the revolution. This time, she wants to join UNSO, Ukraine’s ‘national self-defence force’, another militia which gravitates to the camps to, in her words, “continue to defend the revolution”. She is therefore attentive to her future boss, Vasyl Lutji, as he presents his movement: “For 500 years, we were oppressed by other peoples and there wasn’t any patriotic feeling in Ukraine. This is where the idea came from at the time of independence to create a paramilitary organisation to defend us. We had no choice because Moscow did not share our desire for independence. We also had to protect our borders to preserve ethnic Ukrainian territory, in particular from of Russian immigrants”.

A General enters the room. Everyone salutes. His name is Ruslan Zaitchenko. “We are here to protect the nation, even if that means not always using peaceful methods. This revolution wouldn’t have happened without us because we demonstrate that Ukraine is a proud nation”, he states straight away. Jean-Marie Le Pen is an idol within UNSO. Extreme right-wing movements are gaining in strength again in Eastern Europe and Russia, especially in western Ukraine. UNSO is one of them and ‘The Orange Revolution’ is fertile ground for it. “This revolution demonstrates that people with different opinions can unite because we are all Ukrainian. Yushchenko is a patriot and he understands that we are necessary across the country. But even if Yushchenko is elected, we will keep fighting”, the General adds. The motor of this revolution in all levels of society is most definitely Ukrainian nationalism, whether simply patriotic or, as on the margins, extremist.

UNSO brings together those who have been excluded from the revolution: young people who are not old enough to vote; extremists who aren’t interested in peaceful action. Not forgetting those who just love uniforms and those who display the emblems of skinheads. This worrying phenomenon responds to the need of a section of Ukrainian youth for brotherhood and belonging.

A shaved head at barely 16 years old…

Maxim Pevshen is Director of an SME; he works for Stab. If you need a tent, heating or an army canteen in the camp, he’s the one you go to. This revolution has opened the eyes of this Count descended from Russian aristocracy: “Before the revolution I would never had imagined it, but now I’m sure: I am a patriot. This wasn’t the case in my family though; we spoke Russian. That’s the culture I grew up with. But now I understand that I am a Ukrainian”. For him, as for many others, this Ukrainian identity is principally tied to anti-Russian sentiment. “We are a country but Russians still think of us as a region. They have never treated us as equals even though Kiev is older than Moscow. They don’t see us as independent either. Putin came to Kiev twice to support Yanukovich and that exasperated Ukrainians”. In the Russian imagination, Ukraine is synonymous with Sebastopol, the glorious Russian city founded by Catherine II, and Donbas, home of the Soviet working class where Stakhanov managed to extract 102 tons of coal in a single day. It is a town peopled and colonised by the Russians, as in Crimea. It is part of them.

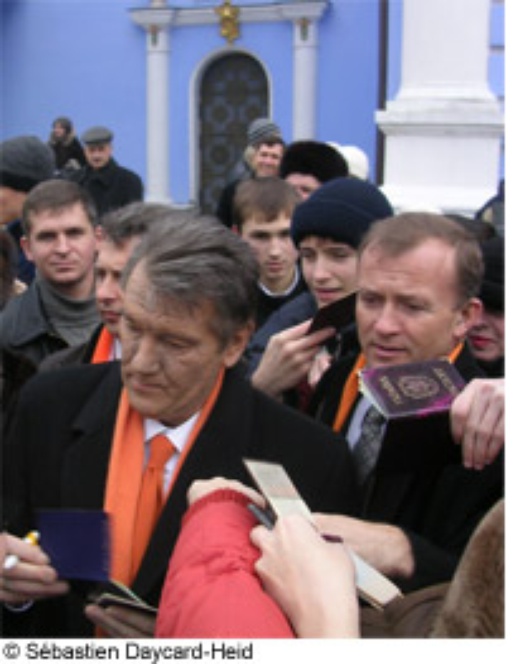

On the morning of the election, Yushchenko goes to the church to pray; he claims to be a strong believer. As he leaves, he signs autographs on Ukrainian passports, proof, if it were needed, of the patriotic dimension of this movement. What is he thinking about? Perhaps that the difficult part is still to come…how will he manage to satisfy all these ‘children of Ukraine’ who are now sweeping him to power?

Translated from Au cœur de la révolution orange - Episode 2 : Les fils d'Ukraine