Arkady Babchenko: ‘Russia is the Germany of 1934’

Published on

Translation by:

brigid hannis

brigid hannis

Sent to the Chechen front at 18, the Russian ‘Novaya Gazeta’ columnist and colleague of murdered journalist Anna Politkovskaya, 31, lays bare the nightmares he endured in his semi-autobiographical 'One Soldier's War in Chechnya'

'Right now, Russian society is extremely cruel.' Arkady Babchenko's face betrays no emotion. He doesn't mince his words, which crack like a whip. ' Xenophobia and nationalism are pervasive. My country is the Germany of 1934.'

He's a tall young man based in Moscow, with a shaven head and fine features. We are sitting in a bar in the heart of the Soho district in central London, accompanied by a Russian - English translator. I can't stop myself from searching for signs of his terrible experiences on the Chechen front.

In 1995, Arkady was 18 years old. He spent his days on the bench of the faculty of law at Moscow University. A possible future which he could sum up in few words: 'A career as a lawyer, lots of money and a nice car.' That's without taking into consideration former Russian president Boris Yeltsin's decision to crush all the Chechen independents in the first Chechen war (1995 - 1996).

Inhumane army

Arkady spent a mere six months in training after enrolling into the Russian military before going into battle. Months in hell, during which the future lawyer and his comrades were regularly beaten by the officers. He staved off starvation, severe cold, enemy attacks, physical torture and madness.

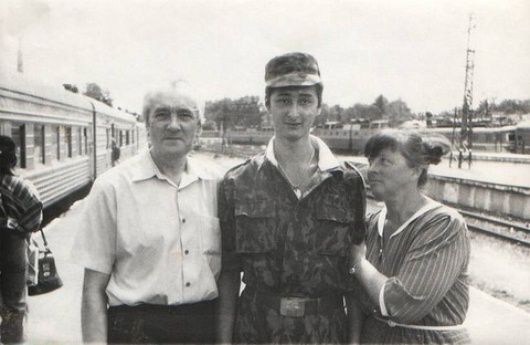

(Click 'x' in the top right hand corner to view Arkady's army memories again)

Arkady was drafted into the army during the first Chechen conflict in 1998 after completing his studies. The following year, during the second Chechen war, he returned voluntarily. Why? ‘I never really returned,’ he says, his answer breaking a pause of several moments. ‘My body was there, but my mind and soul were still in Chechnya. It was madness. I had returned to a world that didn't accept me, and I couldn't bear it. Although, going back a second time was liberating: it was like I had to go back there so that I could complete some part of my life.’

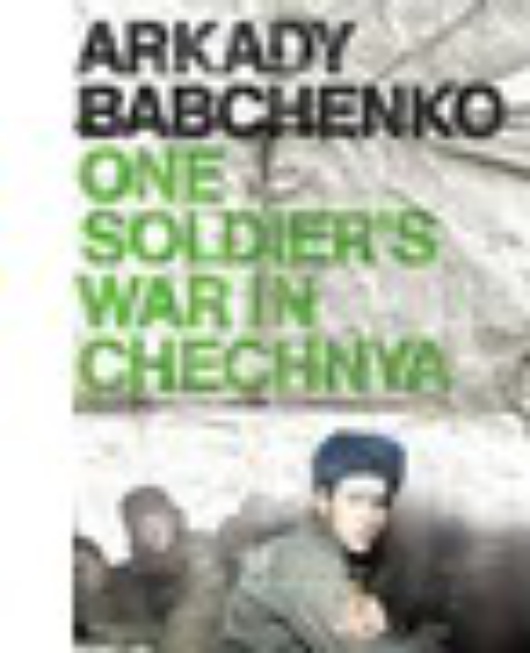

On his second return, a way to ‘purify’ himself entirely, Babchenko had an irrepressible need to put to paper everything he experienced about the dirty war. His book, One Soldier's War in Chechnya (2007), is a compilation of several short stories which he first published separately in various newspapers. It has just been translated by Nick Allen and published in English. ‘The writing process is cathartic. I just couldn't bear it all. My readers are my psychotherapists. When you read what I've written, you feel worse but I feel better!’ Arkady explains, jokingly.

On his second return, a way to ‘purify’ himself entirely, Babchenko had an irrepressible need to put to paper everything he experienced about the dirty war. His book, One Soldier's War in Chechnya (2007), is a compilation of several short stories which he first published separately in various newspapers. It has just been translated by Nick Allen and published in English. ‘The writing process is cathartic. I just couldn't bear it all. My readers are my psychotherapists. When you read what I've written, you feel worse but I feel better!’ Arkady explains, jokingly.

Paying the debt of Chechnyan quagmire

We're laughing, but I know what he means: reading his stories is an experience. They throw you into horror and fascination, into a truth so raw that it comes off the paper, made of blood, blows, madness, humiliation; made of everything that's incomprehensible. A Molotov cocktail at the borders of Europe. Certainly, the readers follow him: the book has been translated into several languages already. Its author has been compared to Tolstoy and Isaac Babel, and he has received Russia's inaugural Debut Prize, given to authors who write ‘despite, not because of, their life circumstances.’

What about the practice of physical abuse within the Russian army? ‘It's no longer a secret in Russia,’ Babchenko says. ‘It's existed for thirty years. We never talk about it in the media, but nothing has changed. They're just the rules of the game. If you have a son, you know one day he'll have to leave for two years to do military service, and that for those two years, he'll be beaten.’ Arkady thinks the problem has to be hunted out of the heart of Russian society. ‘The military reflects society, therefore, if society is cruel, the military will be cruel,’ he concludes.

Is it even possible to believe in humanity after all those terrible years? ‘Niet!’ Arkady answers in Russian. ‘It's only now that I can start to believe in humanity once again,’ he continues by saying, ‘thanks to the passage of time.’

Arkady is now based with his wife and son in Moscow. He works as a journalist for Novaya Gazeta, the opposition's main newspaper. Anna Politkovskaya, an investigative reporter and colleague on the same paper who was assassinated on 9 October 2006. When I ask him why she was murdered, his answer is prudent. Arkady has an idea, but says that the inquiry is in process right now and he ‘doesn't want to thwart the course of justice.’

Boys: you don’t need to kill

Arkady continues to write about the army, soldiers' lives during and after the two Chechen conflicts. He considers it a way of repaying a debt; after all, he still has his life after the blood bath. ‘I don't think that writing about war stops people from fighting, but I hope it provokes a reaction, even a minimal reaction. If only one 15 year old boy reads what I've written and realises that he doesn't have to kill, everything that I'm working towards would be justified.’

His writing is driven equally between a desire to testify to what he's seen and experienced, and to rehabilitate former combatants. It's for that reason he joined up with a former soldier who had fought in Afghanistan, and under whose initiative had created, in 1998, the website called 'The Art of War'. More than two hundred former soldiers from previous wars have the opportunity to express themselves, through art and poetry, as well as in the magazine Iskusstvo Voyny. ‘We won't stay quiet,’ promises Babchenko.

He often refers to the absence of any rehabilitation system for former combatants in Russia as yet another example of a society that qualifies as cruel and apathetic. ‘More than a million soldiers fought in Afghanistan and in Chechnya. Nobody's talking about it, and there's no commemoration. We don't want to stop existing, we want people to know that we've fought, and what war was like. We don't want for people to only know history's official version.’ There should be freedom to reclaim ‘those eighteen years boys who get taken away from their families and sent to the front because of political machinations. Those youths come back without their arms, their legs, having lost their minds, and they are simply banned from society.’

Arkady Babchenko on...

… his native Russia

‘Russia never had aspirations to become a free nation. Slave mentality is a part of Russian mentality; it's a part of who we are and that's terrible.’

... outgoing Russian president Vladimir Putin

‘There are three people in the world whom I hate with all my being: Boris Yeltsin, Grachov (the defence minister who with then-president Yeltsin decides to start the repression on Grozny in 1994, ndlr) and Putin. Two of them are left’

... the magazine 'Iskusstvo Voyny' in which he collaborates with other former combatants

‘The first issue was published in November 2006. We financed it ourselves. And we'd like to have it published in English so that we can reach a wider readership!’

'One Soldier's War in Chechnya, Arkady Babchenko

'One Soldier's War in Chechnya, Arkady Babchenko

Portobello Books (translated by Nick Allen)

Translated from Arkady Babtchenko : « J’écris pour ceux qui se sont battus en Tchétchénie »